My high-school history teacher was infamous for repeating information that she wanted her classes to remember. Anything worth knowing was generally said at least three times, which was her indication that we needed to take notes.

“Reconstruction: 1865 to 1877,” Ms. Thomas would chant.

It was the beginning of my tenth-grade year and the first time I had ever even heard about the political timeline just after the Civil War. During Reconstruction, the federal government put laws in place in attempts to help African Americans adjust after enslavement. Black people were running for political office, getting advanced degrees, and broadening their professional and social endeavors en masse.

However, that sense of Black liberation scared white supremacists, who formed vigilante groups to try and stifle Black people back into systemic boxes of subordination.

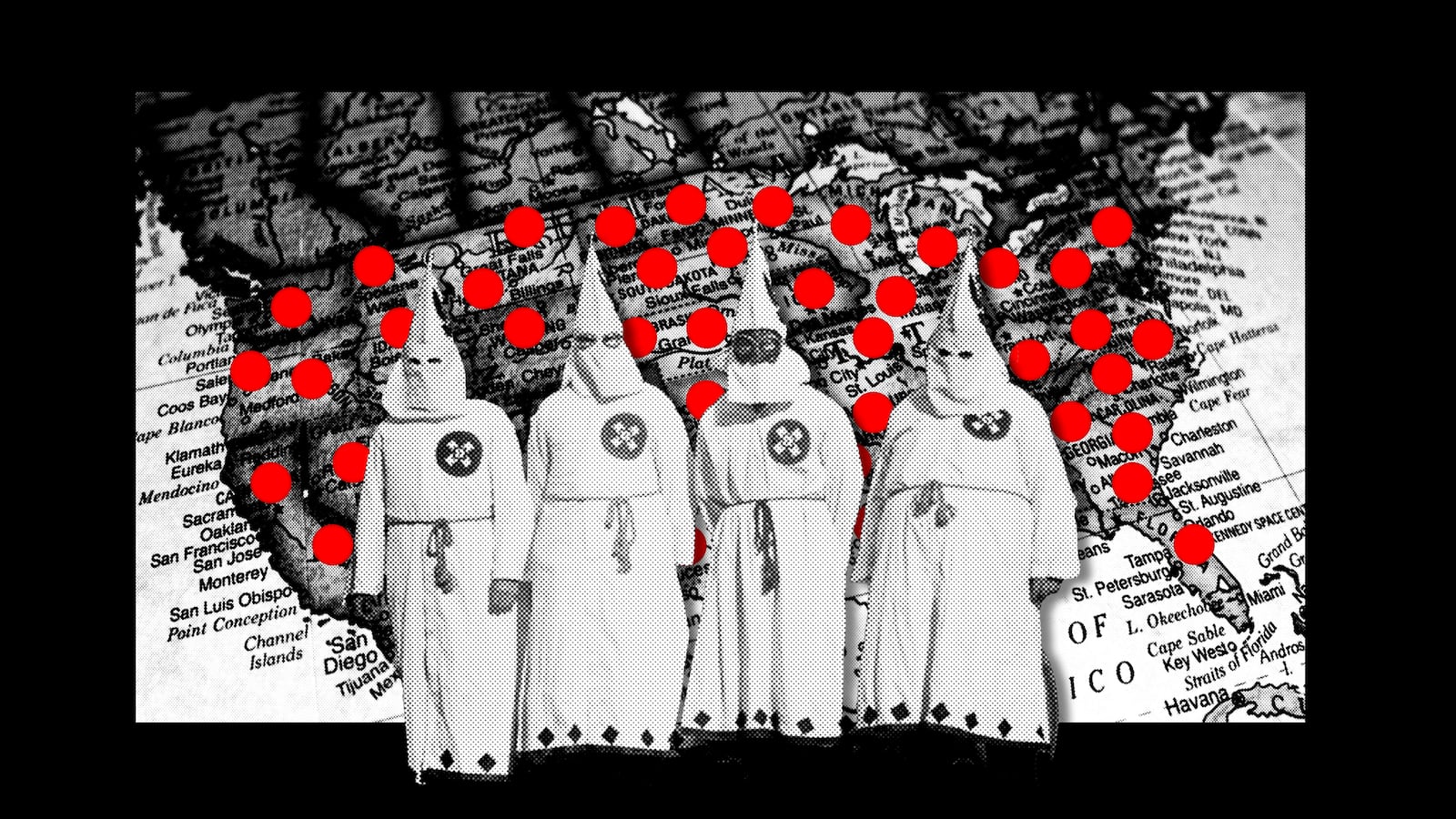

One of those organizations, the Ku Klux Klan was born in Tennessee. Though the homegrown terrorists did manage to slaughter thousands of Black Americans during their early existence, the Klan was unable to grow and prosper due to Reconstruction-era laws and the occasional righteous political leaders who enforced them. But the eventual relaxation of those laws allowed a resurrection of the Klan in the early 20th century, and the organization’s spidery legs of hate were spread throughout multiple avenues of politics, religious communities, and social movements.

Timothy Egan’s A Fever in the Heartland: The Ku Klux Klan’s Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Who Stopped Them (Viking) picks up on the second—and more notorious and harrowing—coming of the Ku Klux Klan when white sheets became the costume norm and burning crosses became regular scare tactics. Released April 4, the work of nonfiction reads like a thriller novel, as if it’s laying the groundwork for a movie script rather than providing the textbook template of historical accounts.

The book follows the true story of Grand Dragon D.C. “Steve” Stephenson and his rise as a white supremacist leader. The heart of the Klan no longer resided below the Mason-Dixon Line. Instead, it swept in massive waves across the Midwest, with Indiana as the ultimate zone of racist-religious-anti-immigrant terror.

Stephenson’s responsibility, Egan quoted a 1924 article from the Indianapolis Star, was “to go forth and spread ‘the principles of pure Patriotism Honor, Klanishness and White Supremacy.’”

The Invisible Empire, as the Klan is commonly known, was revived after a Baptist minister in 1905 North Carolina had a tantrum over the portrayal of the South in a staged version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The minister wrote his own book, The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, to counter the anti-slavery sentiments of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The book was adapted into the film The Birth of a Nation (1915) by director D.W. Griffith, who happened to be homies with the creators of the early Academy of Motion Pictures and Sciences. (The same organization that hosts the Oscars and has been rattled with racist allegations for its lack of diversity.)

The Birth of a Nation set the technical and artistic standards for the up-and-coming movie industry and became propaganda for Klan recruitment as it hailed Black people as sexual predators, political deviants, idiots, and wastes of space when not in positions of servitude. (Ms. Thomas used to say that it was one of the hardest films she ever watched, advised her students never to do so, and said she had to split the three-hour silent film into separate segments to be able to emotionally digest the hateful content.)

Stephenson worked as an idolized recruiter of the Klan, treating the organization like a pyramid scheme with the commission he would make off of each new member—man, woman, or child. (Yes, Ku Klux Kiddies were a thing.) The Klan prided itself on being a group of do-gooder all-Americans who wanted to keep the white race pure. Meanwhile, Stephenson, one of its leaders responsible for 40 percent of its membership and who had eyes on becoming president of the United States, was guilty of everything his prized Invisible Empire condemned: divorce, adultery, illegal drinking during Prohibition, physical abuse, and sexual assault.

Stephenson, simply put, was a menace. He abandoned his pregnant wife in Oklahoma to basically become a white supremacy con-artist of the Midwest. He moved throughout Ohio and Indiana, marrying, illegally marrying, and making broken promises to wed women he allegedly raped to keep them quiet about his crimes.

Nonetheless, with Stephenson’s level of power, he considered himself the law.

A Fever in the Heartland illustrates the fascist orchestration the Ku Klux Klan set in place to infiltrate the country.

“If the Klan is dead, then America is dead,” Imperial Wizard Hiram Evans said in 1925.

Membership in the Klan was a necessity for employment with certain companies. Pastors, judges, mayors, senators, governors were either members or turned blind eyes to its oppressive—and brutal—forces. Laws were passed that were practically kissed by the Klan, including an immigration act that prevented Anne Frank’s family from relocating to the U.S. before the European Jewish Holocaust. Presidents disregarded the Klan’s reign of terror. Nazis were inspired.

The ultimate demise of the Klan’s leaders weren’t outside forces or opponents of their so-called racial purity. Typically, it was a Klansman’s ego that prompted his downfall. In Stephenson’s case, it had been a replica of his predatory behavior finally catching up to him.

Madge Oberholtzer, a working woman who was educated at Butler College, managed to stop Stephenson in his tracks. Afraid that she was going to lose her state government job due to budget cuts, she socialized with the Grand Dragon in an effort to stop the inevitable from happening.

However, Stephenson misread their relationship—or frankly, he didn't care. The Klan leader kidnapped Oberholtzer, forced her to drink alcohol, raped the young woman, and mangled her body in a gruesome sexual act. Realizing the level of power Stephenson had and seeing no other means of escape, Oberholtzer opted to ingest a fatal amount of mercury chloride she managed to obtain. With that unintended matter of self-sacrifice, Oberholtzer got Stephenson on the bad side of the law, which eventually landed him in trial for her murder and his eventual imprisonment.

A Fever in the Heartland is white supremacy’s form of poetic justice. An organization birthed on patriotism and unity was spurred from hate, and it thrived on that bigotry to the point where its members were blind of their own shortcomings.

However, while reading, I couldn’t help but point to the political parallels from a century ago that seem to echo today. Laws are being introduced in multiple states to diminish the rights of transgender people. Florida’s lawmakers are fighting tooth and nail to prevent historical accuracy from being taught in schools. Books are barred that are deemed too controversial to an antic—and false—American dream.

Voter suppression is an ongoing issue during elections. Neo-Nazis marched with torches at the University of Virginia (my alma mater), trumpeting white power seemingly in homage to those turn-of-the-century lynch mobs and cross burnings. And we’re still enduring the aftermath of a former president who wanted to build a wall to keep out Latinos he deemed were “killers” and other immigrants from “shithole countries.”

Though the Ku Klux Klan may not officially be feared as a collective organization as it once was, remnants of its social, political, and psychological power still fester in the soil.