Wearable technology is having its moment.

Everywhere you look, new gadgets that can be attached, strapped on, or donned arrive on the market. On my desk alone, there’s the heart rate monitor/training watch I got last year. The Fitbit I received as a holiday president from IAC (Thanks, Mr. Diller), and the meditation goggles that Psioplanet sent me to try out. I’m eager to try out the Hexoskin shirt, a sort of $399 Under-Armour-meets-emergency-room garment that displays your vital signs. Meanwhile, a bunch of savvy companies are trying to revive the digital watch: there’s the Samsung smartwatch, the Pebble, the much-rumored iWatch.

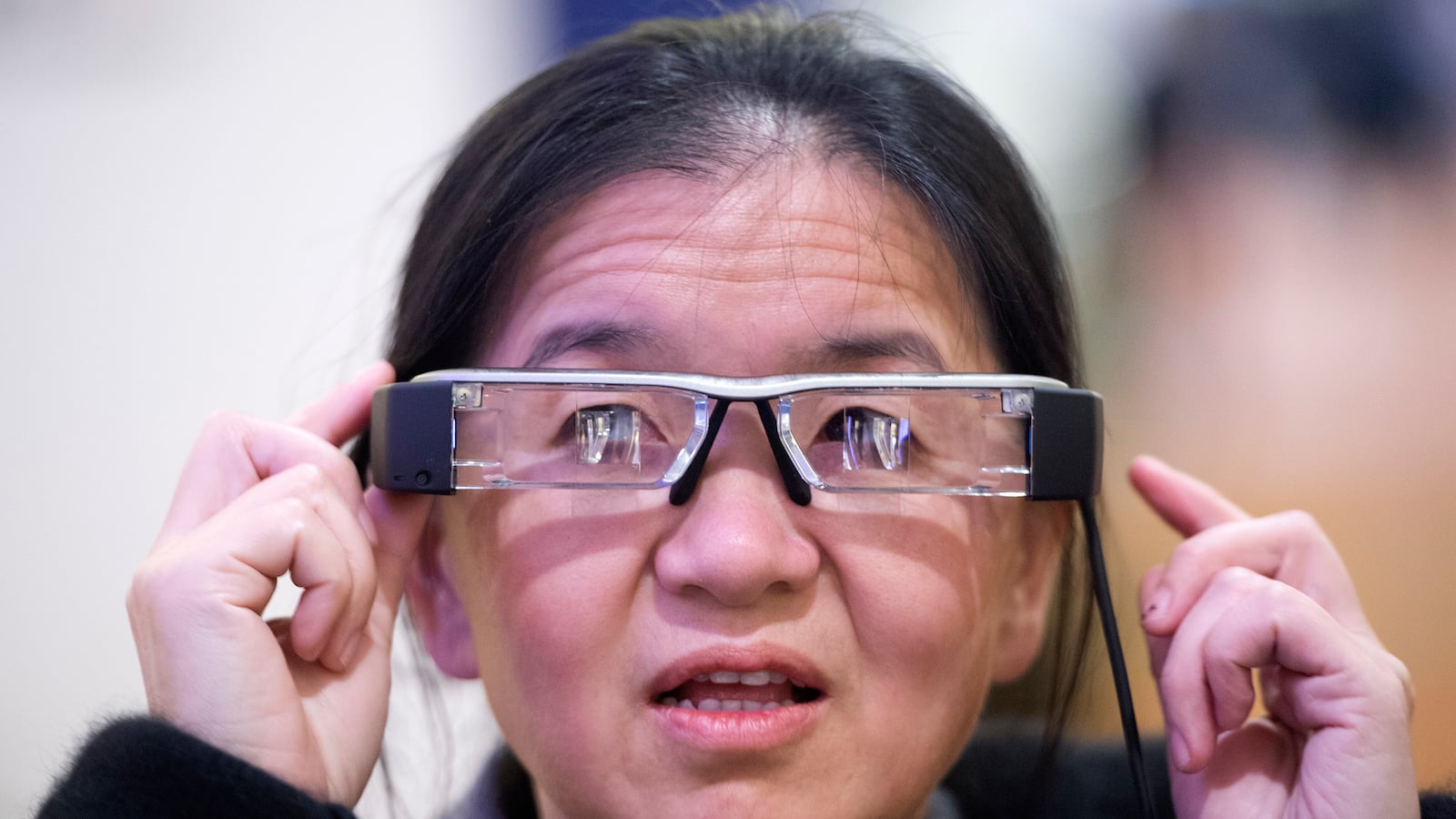

Wearables are a huge thing at the Consumer Electronics Show currently unfolding in Las Vegas. Participants have seen Intel’s Smart Onesie, an all-enveloping baby monitor, Epiphany, smart glasses that can stream Facebook video in real time, and vibrating underpants from a company called OhMiBod.

Analysts are busily pumping out reports trumpeting the prospects of the sector. U.K.-based Juniper Research projects the number of wearable devices shipped will rise from about 13 million in 2013 to 130 million in 2018, and that the size of the market will jump from $1.4 billion in 2013 to $19 billion in 2018. Business Insider Intelligence projects shipments of 100 million pieces in 2014 and believes the market will ultimately be worth about $12 billion per year. IMS Research said the market for wearables was already at $8.5 billion in 2012, with 96 million devices shipped, and that it should grow to 210 million devices worth $30 billion in 2018. (Note: IMS’s definition of wearables includes industrial and military applications, not just consumer ones.)

These are widely divergent forecasts. And that’s typical when industries are in their relative infancies and in hypergrowth mode. What’s more, multi-year projections about technology adoption and spending should be taken with a grain of sale. Imagine what a 2007 forecast about smartphones would have projected for 2013—and just how woefully it would have undershot reality.

Of course, the electronics industry and the folks at CES are so excited about the prospects of wearable technology in part because some of the biggest components of the electronics industry have run into trouble. In many sectors—televisions, desktop pcs, printers, even smartphones—engineers have been too successful at developing cheap, highly functional products. To encourage consumers to dispose of products that work perfectly well and can last several more years, they’re stuck rolling out minor tweaks and changes, or by offering cheaper versions of existing products.

The real money in technology lies in creating entirely new classes of products, forging new markets, and making people realize they have been missing certain things in their lives. But it’s not clear that wearable technology can be that thing. Sure, the young market could blow to become the next smartphone—a mass industry that creates its own economic ecosystem. Or it could be develop into a series of niche products that add up to a bunch of good businesses and a bunch of failed ones. Or it could be a fad that will fade like the Macarena.

My money’s on the second option.

Consider the smartphone. Sure, skeptics abounded that the expensive iPhone and its imitators would become the new standard. But smartphones represented important innovations to a series of mass behaviors. Before the iPhone came along, people were carrying music around, making phone calls and taking photos, sending email, playing games, and accessing information and services on the internet with hand-held devices. Hundreds of millions of people were accustomed to toting these objects around, plugging them in to recharge them, and using them. Smartphones were just a much better, more convenient, all-in-one version of a bunch of popular devices. Switching to smartphones didn’t require a big change in consumer behavior.

But wearable technology promoters are asking much more of their customers. They are asking them to develop new habits very quickly, and to stick with them. The idea behind many wearable tech products is not simply to sell the hardware, but also to sell services like, say, diet and exercise advice to go along with your Up band. But that requires people to incorporate these gadgets into their daily lives in a way that they haven’t before.

Unlike a phone, wearable technology is an add-on, an accessory, something that comes on top.

And that doesn’t always happen. Everyone in our office received a Fitbit as a holiday present from our corporate parent. In the office today, only about one-tenth of the 60 people were wearing their Fitbit bands. I tried mine for a few days. Then I took it off to go into a swimming pool and never really put it back on. By the second week, I was ignoring the emails telling me the device needed to be charged. It now sits on my desk, alongside the Sony Cyber-shot camera, a Sony Bloggie camera, two defunct Blackberries, and a defunct wireless modem.

Unlike a phone, which you take because it is a communications device, your email, your work, music, and various payments—all things you can’t really get through the day without—wearable technology is an add-on, an accessory, something that comes on top. People who wear prescription glasses literally can’t leave home without putting on their specs. People who leave the house without Google Glass can function just fine. And the insertion of technology into clothes raises a host of potential problems: what if you outgrow the shirt? How do you launder electronics? Will you really wear a small set of garments over and over again just because they can tell you what your heart rate is?

And so whereas the universe of smartphone addicts is huge, I’m guessing the universe for health-and fitness-related wearable technology is more limited. Yes, there are a large number of people – cyclists, fitness nuts, food neurotics, disciples of Timothy Ferriss – who like to quantify and measure everything they put into their body, and everything that comes out of it. And so I’m guessing that people with lots of disposable income will experiment with wearable tech, and then probably not use them all that much.

Meanwhile, the vast majority of people are likely be indifferent to the leisure-and-entertainment suite of products. CES is a huge trade show. But the number of folks who dork out over the latest cool gizmos is actually a relatively small slice of the human population. In the real world, walking around with Google Glass is as likely to make you a target of opprobrium as it is a target of envy.

That’s not to say all these products will bomb, or that wearable technology won’t be a big business indeed. It’s just likely that many of the most-hyped consumer products—like Google Glass—are likely to be niche products rather than mass ones. What’s more, it is also likely that the most enduring wearable technology business will be built not on discretionary spending, but on necessary spending. Put another way, the ones with the most viability may be those making them for people who need wearables for work and survival, rather than for leisure and play.

People who have chronic conditions like diabetes or kidney disease, for example, are much more likely to benefit from health-related wearable technology than casual joggers. And so it wouldn’t be surprising to see wearable body monitors become integrated into medical treatment. Google Glass and other internet-enabled specs offer a valuable service to people who like to surf the internet while they’re walking around. But they offer a much more valuable service to people who need to access lots of information on-the-fly without using their hands: think of doctors, or salespeople, or soldiers and spies.

Like personal computers, wearable tech might wind up being something we use most in the office.