DABIQ, Syria—When the so-called Islamic State raised its black flag over this farm town in northern Syria some three years ago, extremist volunteers, mostly foreigners, had already begun destroying ancient artifacts. They went on to vandalize the town’s cemeteries, close its schools, and turn the municipal offices into a prison.

The conquest drew little notice at the time. It didn’t compare to ISIS’ capture two months earlier of Mosul, Iraq’s second biggest city, nor Abu Bakr al Baghdadi’s brazen proclamation of the Islamic Caliphate.

The big news in August 2014 was U.S. military intervention after ISIS fighters attacked the Yazidi minority in Iraq, raped and enslaved the women. And then the beheading of American journalist James Foley and other prisoners.

But for ISIS, the capture of this town 7 miles south of the Turkish border was the fulfillment of a prophecy.

According to a Hadith, a saying attributed to the Prophet Muhammad, Dabiq was to be the scene of an apocalyptic battle between Muslims and Christians. One-third of the Muslim fighters would flee the scene, one-third would die as martyrs, and the remaining third would defeat the Christian forces, opening the way for the End of Days.

If nothing else, the capture of Dabiq was the fulfillment of a public relations prophecy. Two months earlier, ISIS issued a glossy 50-page webzine titled Dabiq that would become its principal publication.

But when Dabiq fell last October, its defenders fled without firing a bullet.

Today it’s still unclear why ISIS would give it up so easily to a Turkish-backed Syrian rebel force.

There’s no mystery about what ISIS did to the town, however. There was no effort to turn Dabiq into a showplace for the cult. ISIS instead cut the town’s ties with the world, imposed restrictions that halted farming, and treated its population as a nuisance.

Dabiq was a prop in the campaign to recruit foreign volunteers for suicidal warfare, and the townspeople were considered superfluous, or expendable.

“They used to tell the people of Dabiq, ‘You are not the people of Dabiq who will witness the end of times. You will not have the honor to be in this place,’” said Nuri al Ahmad, 43, an agricultural engineer who stayed in the village. Perhaps 4,000 of the 12,500 population remained during the ISIS occupation.

Ahmad worked in construction during the time ISIS was in control, and tended his vegetable garden.

ISIS ordered residents to hand in their satellite dishes and receivers but didn’t collect television sets, so the only station anyone could receive was regime television beamed from Aleppo. ISIS threatened to arrest anyone caught with a mobile phone, and the town became disconnected. Daily, there was a 6 p.m. curfew, and violators would be whipped.

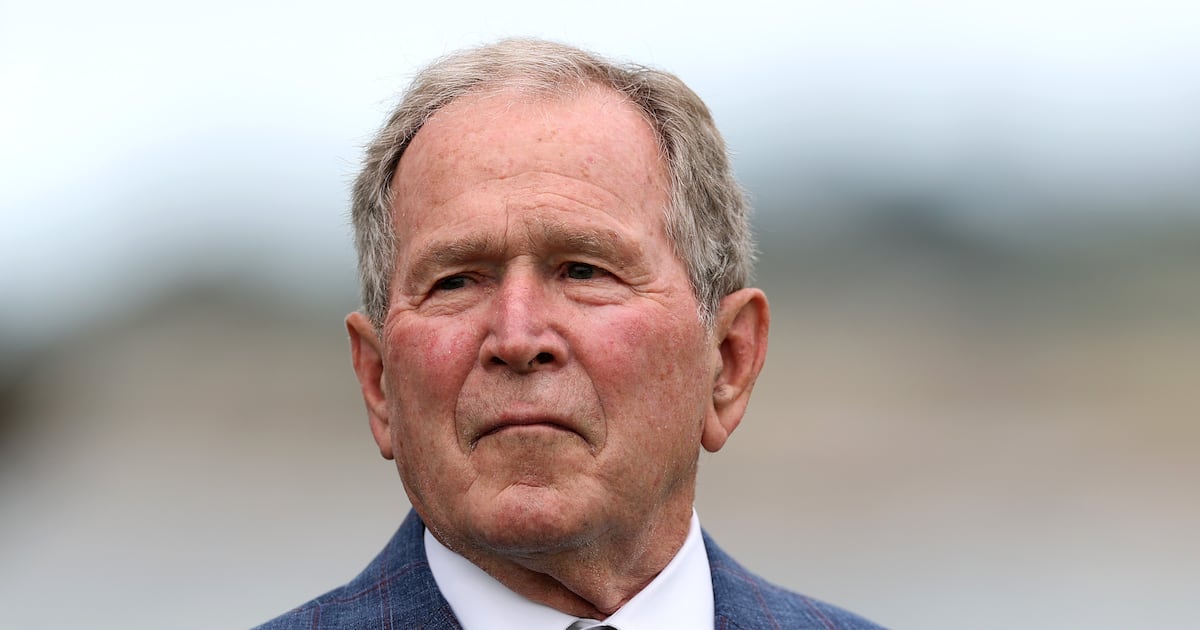

Fahim Issa, deputy commander of the Sultan Hamid brigade of the Free Syrian Army, points to the location where he led troops into Dabiq last October, ousting about 100 Islamic State fighters. A prophecy of the Prophet Mohamad, in a Hadith by one of his companions, held that Dabiq would be the site of an apocalyptic battle between the armies of Islam and the armies of Rome. But it fell without a fight.

Roy Gutman/Daily BeastISIS “were just using Dabiq for the media,” said Imam Ahmad Yassin Khatib, the town’s cleric.

“They destroyed more than they built,” said Mohamad Hamedi, 44, the head of the town council, who spent three months in an ISIS jail because his brother was a fighter in the Free Syrian Army, then was freed in a prisoner exchange. “They used this town for propaganda.”

Dabiq and the surrounding villages grow wheat, beans, and chickpeas, but the land went fallow, because ISIS prohibited women from working the fields.

Dabiq and the surrounding villages had produced the daily bread at three fully automated bakeries—until ISIS dismantled the ovens and took over distribution.

Dabiq had a historic transport link to Europe and the Levant, for the nearby village of Akhtarin is a station on the Berlin to Baghdad railway—until ISIS pulled up the tracks.

And it had a profound connection to history in the tomb of Suleiman bin Abdelmalek, an eighth century Umayyad caliph, who ruled the Islamic empire from Damascus and was buried on a hill overlooking the village.

Also buried there were the caliph’s two sons and a disciple of the Prophet Muhammad. That was the tomb ISIS operatives blew up just before taking Dabiq. They also destroyed 15 tombs in the village cemetery.

On that same hill, ISIS hoisted its trademark black flag, 15 feet high, with an even bigger one about 40 feet high on a hill overlooking the nearby village of Tel Rshaf.

It was on Dabiq hill that “Jihadi John,” a Yemeni-born Briton, beheaded Peter Kassig, a young American aid volunteer whom ISIS had taken hostage. Many others were executed there, but villagers didn’t know if they were foreigners or Syrians, said town mayor Hamedi.

That ISIS was able to fly its flags with impunity for 28 months continues to raise questions about whether the Assad regime, which has consistently portrayed the six-year-old national uprising as a Sunni extremist plot, had a role in ISIS’ takeover of Dabiq.

“The regime never challenged them on the flags,” said Ali Abu al Jud, a local journalist. In fact it rarely challenged several of the havens ISIS has long enjoyed, including the self-styled capital of the “caliphate” in the city of Raqqa.

ISIS operatives blew up an ancient tomb when then captured Dabiq in northern Syria not quite three years ago, then they went on a familiar rampage in Dabiq and the surrounding villages, destroying cemeteries on the basis of their extremist belief that headstones are idolatrous.

Roy Gutman/Daily BeastThere’s little question that the regime has had a relationship with ISIS or that the two forces collaborated in operations against Free Syrian Army rebels. Regime officials once bragged to their U.S. counterparts that regime intelligence had penetrated the Islamic extremist group.

In the event, the Assad regime did nothing to block the Free Syrian Army takeover of Dabiq. Most probably that was because Syria’s major arms supplier, Russia, had acquiesced to the initial stages of the Turkish-backed operation against ISIS when it began late last August.

The web magazine ISIS named for Dabiq was a bizarre publication. It had a veneer of religiosity, with the final issue containing more than 100 references to the Prophet Muhammad and 385 to Allah. But among the features were articles praising the slaughter of civilians in ISIS-affiliated terror strikes, interspersed with jargon-laden treatises on Islam and Christianity.

Imagery of fire and brimstone, infernos and rivers of molten lava graced most issues along with lurid photos of ISIS victims killed in suicide bombings or executed by ISIS. There would be links to snuff films, in which black-hooded ISIS executioners beheaded captives in orange jump suits.

British photojournalist John Cantile, who went from ISIS captive to the narrator on ISIS propaganda videos, was a Dabiq columnist for a time.

Yet a look through half a dozen of the 15 issues raises the question of who was the target audience other than psychopaths seeking pseudo-religious cover for killing civilians.

“It’s stylishly presented, but if you don’t know the key concepts of this particular version of the history of Islam, it’s just a bunch of gobbledy gook,” says Graeme Wood, author of The Way of the Strangers, a new book on ISIS.

Dabiq the magazine ceased publication after the fall of Dabiq the town. But the force that liberated it had the town’s legend in mind when it began the offensive late last September. Turkey and the U.S. provided military support, but the fighters were all Syrians. There would be no “crusaders” among them.

“We were careful because of the myth,” said Fahim Issa, the deputy commander of the U.S.-supported Sultan Murad brigade, which has a large component of fighters from the Turkmen minority. “Our strategy was to surround them, so they couldn’t fight in Dabiq,” he told The Daily Beast.

His biggest losses were in Rshaf, the site of the outsize black flag. There ISIS cobbled together a surprisingly effective defense, setting up cameras along the main street that were powered by fuel cells. ISIS fighters, monitoring them over the internet, would detonate mines when rebel forces approached. Issa said eight rebels were killed and 10 wounded in Rshaf.

But in Dabiq, the 100 or so ISIS fighters fled without a fight.

“They didn’t even shoot at us,” Issa said.

Before they departed, ISIS leaders put out the word that Dabiq “would be the smaller battle. The big epic battle is to follow,” said Imam Khatib, the town clergyman. “It took them only 17 minutes to run away.”