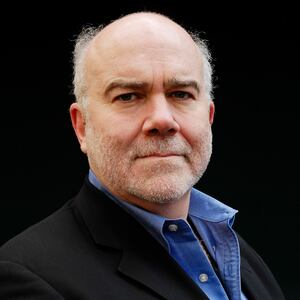

Jacques Pépin, who likely needs no introduction—let’s just say he’s one of the most accomplished and inspiring French cooks and educators to have ever rolled an omelet from a pan—is also an accomplished painter.

His paintings are sunny, happy and funny in a way that perfectly reflects Pépin himself—radiating a hospitality that is rooted in kindness. The paintings are loose and bright, and they often depict cheery bowls of fruit and portraits of dignified chickens. But this isn’t just a hobby and Pépin takes his craft seriously and sells his artwork. While buying one—or a signed print—would have been a wonderful idea last year, this year it comes garnished with the knowledge that it helps support the Jacques Pépin Foundation, which, seeing as how it is 2020, is having a pretty rough year.

The organization was started by Pépin with his daughter Claudine and her husband Rollie Wesen, who is a chef and professor at Johnson & Wales University. Together, with a small team, they work to provide a curriculum, materials, connections and visibility to a network of community kitchens across America.

Community kitchens serve many purposes, including, of course, feeding people as well as offering cooking classes. The goal of the foundation is to provide a culinary education and job training to people with barriers to employment. This isn’t just about making the perfect soufflé or the chewiest baguette, Pépin wants to change lives and three years ago there were in fact 750,000 open positions in the food service industry.

Pépin told me they aren’t trying to get people to work at Per Se but in all kinds of establishments. “There are 25,000 restaurants in New York,” he said, “Small eateries, family run. We can teach that.”

When I recently spoke by telephone to Wesen to discuss the mission of the foundation and the challenges it faces during these tumultuous times, he asked me: “Do you know that 70-percent of people have worked in food service?”

The idea, as Wesen explained it to me, is multifaceted. On the one hand, food service has a low barrier to entry and there are several million people in America who could use a break. But when he went out into the field (he wrote his dissertation on community based culinary education programs, so his research is serious) to ask what it was that employers wanted in potential hires, they answered that they “just wanted someone who understands the basics.”

“But what does that mean?” Wesen asked. “It’s a moving target.” After all at a clam shack, you have to know how to fry, but you don’t really have to understand braising. The culinary education needed to work at a bakery is different than what is required at a taco stand.

After much thought Wesen has whittled down the key things that are common across most food related jobs: knowledge of ingredients, food safety and an understanding of allergens are all key. A repertoire of basic technique is vital. The Foundation has worked on creating modules with basic learning objectives and what Wesen calls “a laser focus on basic technique.”

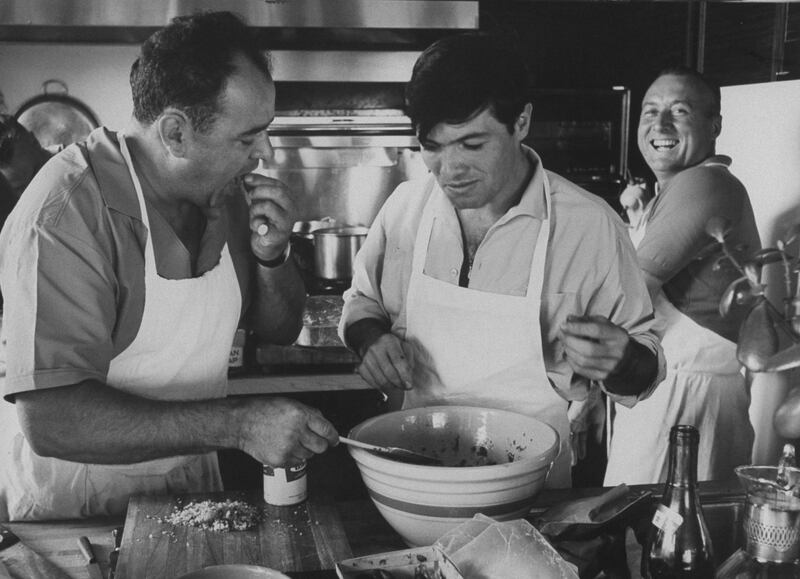

This, of course, is right in Pépin’s wheelhouse, since he literally wrote the book on cooking techniques.

“Jacques taught a class in Hartford recently,” Wesen told me, “in which he showed people how to peel a carrot.” It is, after all, his simplest techniques that are most enchanting. Pépin’s goal has always been to find—and teach—“the easiest and quickest way to the best result.”

“I’m concerned, though,” said Wesen, “that the gap we were closing has gone away.”

The restaurant industry has been hit hard by the pandemic. Those 750,000 jobs might no longer exist. Restaurants are closing and the insecurities inherent to the industry have been revealed.

“I’m an optimist,” said Pépin. “The small type of restaurant, where we eat outside, they will be there.”

Wesen and Pépin both feel confident that the industry will survive and be reborn. “It will change, of course,” said Pépin.

Within the next six months, Wesen predicts that we’ll all have eaten something spectacular, prepared with expertise and care, and handed to us through a takeout window.

But that does nothing to ameliorate the pressure on community kitchens across America.

“Our kitchen partners are experiencing an incredible need.” Wesen told me that demand for their services is up 60 percent, but that volunteering and contributions are down 90 percent.

The foundation wants to help address these needs.

“The work makes so much sense,” Wesen said. “It has a direct impact on improving lives and strengthening communities. This is a time of desperate need, but being able to cook for yourself and your family will never go out of fashion.”

The morning we spoke, Pépin had in fact received three letters from people who were grateful that they had learned to cook. It’s not just about the jobs. “The other aspect is sitting down at the table. Family structure is very important to me.”

Just as the community kitchens have struggled, so too has the Foundation. It was projecting a stellar year, looking forward to a 50 percent gain in revenue over what was brought in last year. Instead, they will likely net something like 15 percent of their projected revenue. The Foundation has a lean staff and its overhead is slight, so Wesen is confident that they’ll weather the storm, but it will not be easy.

In the fall, they plan to launch a series of cooking videos—they have commitments from at least 30 big name chefs already. Each will be recorded in a person’s home, and together they’ll build a video sampler and cookbook.

Right now, however, the foundation is selling signed prints of Pépin’s paintings.

“I used to try to validate my painting,” said Pépin. “I don’t have anything to prove, I do what feels right.” When he talks about the process, he slips back and forth between talking about cooking and talking about painting. “You taste, you add, you taste, you add,” he says, having built a metaphor for how painting is like cooking sweetbreads. “I rely on my feeling, my taste, my imagination.” He tells me that he doesn’t look at a painting and think that he needs to add blue indigo to a certain part of it, he just looks at what is in front of him. “It’s very impulsive, very subjective.”

“At the end, it should register on your palate,” he said. He meant both palette and palate, I’m sure of it.

Pépin talked about how a good cook could cook the same chicken dish 15 times and it would never be the same, because “for it to be the same, you have to change it each time.” You have to adapt, he means, to the chicken, to the pan, to your mood, to the heat. Just as we all have to adapt to the times. He’s optimistic about that, too.

“We’ll make it,” he told me, “if we keep drinking enough wine.”