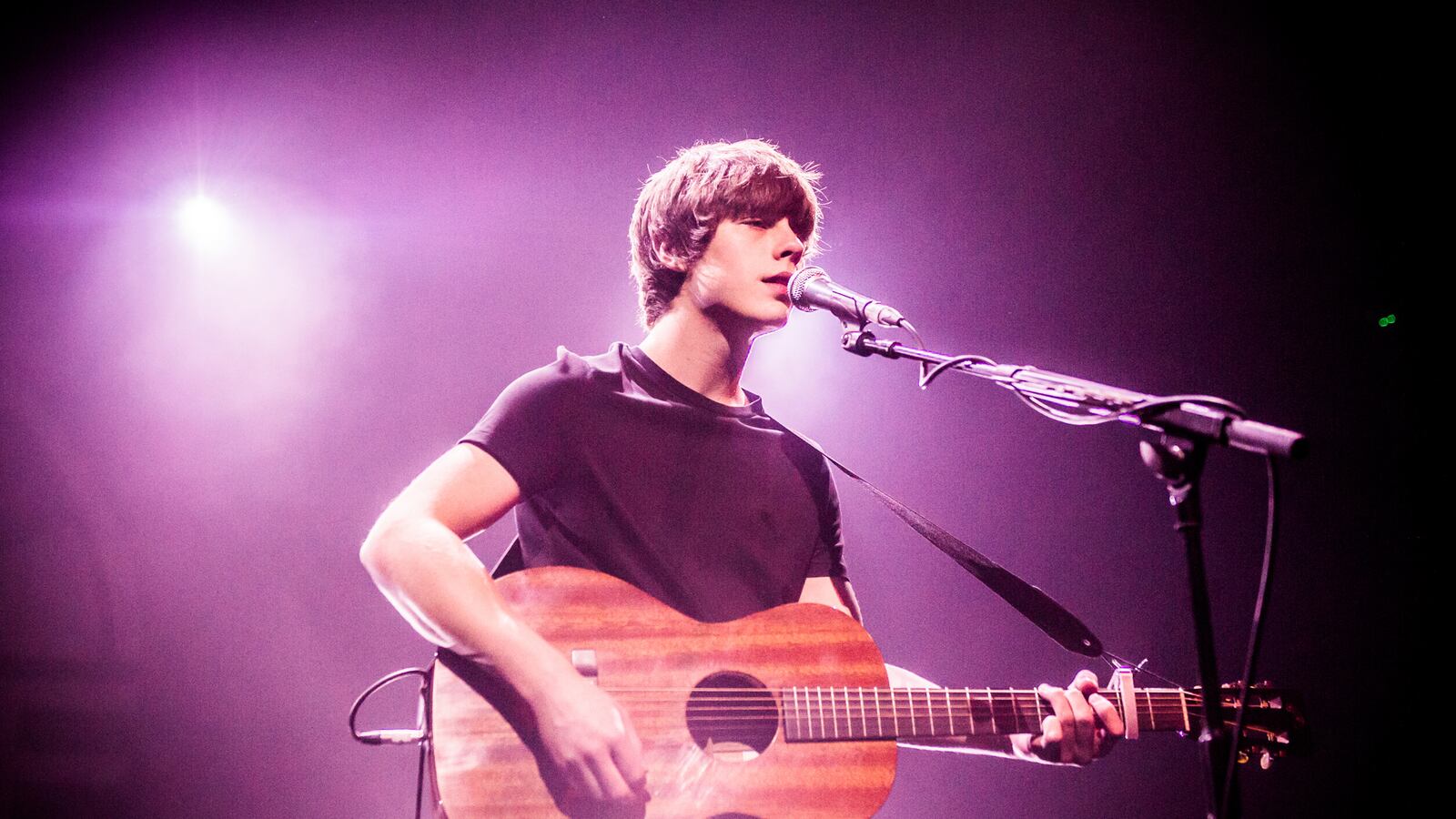

Jake Bugg recently dated a supermodel. Jake Bugg has taken to wearing leather jackets and Prada shoes. Jake Bugg’s debut album, Jake Bugg, landed at the top of the British charts and went on to sell more than 450,000 copies. Jake Bugg likes to diss One Direction. Jake Bugg has been called “the East Midlands Bob Dylan.” Jake Bugg looks like a lost Gallagher brother. Jake Bugg is 19. Jake Bugg isn’t even Jake Bugg’s real name.

In short, Jake Bugg should be a rather irritating character—a posturing rock brat, perhaps. And yet when I reach him in England one recent afternoon, all he wants to talk about is time signatures.

Bugg’s sophomore LP, Shangri La, arrives in America this week accompanied by a lot of hype and a lot of backlash. Hype because for the last two years Bugg has been described by many in the British music press as a savior of sorts: an “authentic” rock star who writes songs about drugs, violence, and growing up poor in a Nottingham council estate; a throwback guitar hero who shuns the plastic pop conventions of our Auto-Tuned age and has the good taste to emulate “real” musicians like Buddy Holly, Johnny Cash, and Bob Dylan instead of, say, One Direction.

The backlash, meanwhile, has arisen more recently. Some Brits seem to have concluded that Bugg is not, in fact, as “genuine” as he claims to be. In a recent Guardian essay, Alexis Petridis wrote that Bugg’s so-called authenticity is “an idea that’s easy to mock” because “much of his debut album was co-written with a succession of songwriters-for-hire, including Matt Prime, also responsible for a string of hits by Victoria Beckham, Kylie Minogue and TV talent show winners Olly Murs, Liberty X and Will Young.” Petridis concludes that Jake Bugg is “as artfully constructed as any manufactured pop record,” with “faux-vinyl crackles” that are the “sonic equivalent of distressing furniture to make it appear antique.”

But as I listened to my advance copy Shangri La earlier this month, I couldn’t help but think that both positions—Bugg is Bob Dylan, Bugg is Kylie Minogue—are a little too extreme. So I decided to go straight to the source—which is how Bugg and I have hit upon the topic of time signatures.

Up until this point, Bugg has been a polite but rote interviewee; the most vivid description of Shangri La he’s been able to muster is that “it feels more like an album than just a collection of songs.” But then I ask about one song in particular: “A Song About Love.” With its delicate Nick Drake verses and big, swooping chorus, it strikes me as a departure for Bugg—more mature, more complex, and more beautiful than his earlier work.

Suddenly, Bugg perks up. He begins to tell me how everyone urged him to change it. “As I wrote it, it had a very weird timing issue in the verses,” Bugg explains. “Ballads are usually in 4/4. So Iain [Archer, Bugg’s songwriting partner] said, ‘You really need to make it straight. You need to make it 4/4.’ Then my manager heard the demo and said the same thing. And I was really, really, really against it. I was like, ‘That just kind of takes away the whole feel of it—all the emotion I’ve put into this song.’”

Rick Rubin, who produced Shangri La—the album is named after his studio in Malibu—was also skeptical. “When Jake first played it for me acoustically, I thought he was making a mistake on the timing of the verse,” Rubin tells me. “It alternated between 4/4 and 3/4, back and forth for every line. My first instinct was to try it straight in 4/4 and Jake said, ‘That’s not how the song goes.’ I wasn’t sure it would be possible to have drums playing in the verse without it sounding awkward.”

But Bugg persevered. “All the musicians sat ‘round trying to work out what I was doing,” he says. “I didn’t come up learning anything technical, so I didn’t know what I was doing. I was just doing what I do.”

According to Rubin, it took “about two days” to capture “the groove that’s on the record, which keeps the song as Jake heard it.” Listening to “A Song About Love” now, he is convinced that Bugg was right and that the “professionals” were wrong. “Although it’s a bit unusual the first time you hear it, by the third listen it’s one of the coolest and most original elements of the song,” Rubin says. “It’s remarkable he heard it that way in his head with no rhythm playing.”

Bugg is chuffed as well. “I just think if I would have changed it to a straight 4/4 it would’ve probably got boring somewhere halfway through,” he adds. “It would have taken something away for me, for the person singing. You’re not thinking about it. You’re not trying to be clever. It’s just how the song needed to be.”

It’s just how the song needed to be. Bugg might not be Bob Dylan—a world-changing artist who bursts forth fully formed with no need for direction or collaboration. But he’s also not a pop product. You can hear his talent all over Shangri La: the second chord of the chorus of “A Song About Love”; the acoustic quirk of “Kitchen Table,” Bugg’s attempt to capture the “spookiness” of John Martyn’s 1973 folk-jazz classic Solid Air; the lovely, lilting alt-country melody of “Pine Trees”; the Sun Records stomp of “There’s a Beast and We All Feed It”; the rapid-fire hooks of “Messed Up Kids”; and throughout, Bugg’s strong, strange, uncompromising voice—a reedy wail that sounds like it would be more at home in Appalachia than on FM radio. Above all, Shangri La is a stellar album—a cohesive, fat-free mission statement. That’s a rarity in today’s a la carte iTunes culture.

***

Shangri La began almost by accident. Rubin—the bearded legend who produced LL Cool J’s Radio, The Beastie Boys’ Licensed to Ill, “Walk This Way” by Run-D.M.C. and Aerosmith, the Red Hot Chili Peppers’ Blood Sugar Sex Magik, and Johnny Cash’s American Recordings series, among many, many others—heard “Lighting Bolt,” the third single from Bugg’s debut album, on a visit to the UK and was “impressed with how young he was and how accomplished he sounded.” A few months later, Universal was struggling to find someone who could re-record “Broken” for release as the LP’s final single. The brass contacted Rubin, and soon Bugg was en route to Los Angeles, where Rubin had assembled a band of crack players—the Chili Peppers’ drummer Chad Smith; Elvis Costello sideman Pete Thomas; guitarists Matt Sweeney and Jason Lader—to back him up. “Jake needed to be surrounded with great musicians who had the sensitivity to support what he plays in a natural musical way,” Rubin says. “It’s not as easy as it sounds.”

Bugg was impressed with the set up at Shangri La. “The first time I met Rick, I flew into L.A. and then we drove up to Malibu,” he says. “It was a beautiful drive. I got to see the Pacific Ocean. I’d never seen anything like that before. And then I met him—a big guy with a big beard sitting there, with the wind coming through the windows.”

Bugg’s first task was to re-record “Broken.” But he didn’t stop there. “Since the band was already assembled, I asked Jake if he had any other songs written,” Rubin says. “He did and we started recording them. Each one was better than the one before, and I was wondering where these songs were coming from. His writing had a depth and maturity beyond his years.”

Rubin was struck by Bugg’s balanced approach to the process. On one hand, Bugg had “strong ideas about how the songs were meant to go”; on the other hand, “he was open to collaboration to make the songs and the recordings as strong as they could be.” Sometimes Rubin would simply edit “to create the most satisfying shape for the song”; sometimes he would “request” that Bugg “better a melody or write an additional part to strengthen the overall structure.”

Bugg appreciated the input. “All the songs I had for this album were just ideas I’d come up with on the road,” he says. “Rick kind of dragged them out of me and made sure I turned them into songs. And he helped me by saying, like, why don’t you try repeating this line for the chorus. Very simple advice but very effective as well.”

For Bugg, songwriting—mainly with Iain Archer, formerly of Snow Patrol—is a similar story. At first he balked when his record company suggested that he work with established songwriters to hone his compositions. “Nowadays when you get a record deal people want to put you with songwriters,” he says. “I used to be very defensive about that. Like, ‘What’s wrong with what I do?’ But then I thought, ‘I’m 17—I could probably learn a lot from experienced people.’ So I met Iain and we just became good friends.”

Bugg describes Archer as “more of a guide than someone I write songs with.” Typically, Bugg will show up with “a few ideas and a few riffs”; Archer helps to mold them into a completed song. “Being my age I get distracted quite easily,” Bugg says. “Iain’s good at making sure that I finish the song and then sit down and go through the lyrics, swapping out and changing them. For every two ideas I have he’ll give me an opinion on which he thinks is the best.”

If that makes Bugg’s music “manufactured pop,” then so be it. But ultimately I think that arguing about authenticity is silly, especially in this day and age. For a brief period in pop history—the ‘60s and early ‘70s, pretty much—auteurism was music’s highest virtue. The more an artist did by him- or herself, the better. But before that interregnum, pop was all about collaboration—producers produced, songwriters wrote, singers sang, and session musicians played—and in many ways, it’s been all about collaboration ever since.

Consider Adele. No one criticized Ms. Adkins when she worked with six co-writers and six producers on the mega-selling 21; in fact, she was widely praised for bothering to write in the first place. Bugg is a similar sort of young artist: a strong, distinctive British singer with personal lyrics and a retro vibe. Just because he looks a bit like a Beatle and sounds a bit like Dylan doesn’t mean he should be held to different standard. Even John Lennon and Paul McCartney relied on producer George Martin to realize their vision. What matters is the music, and Bugg’s music is uncommonly good.

As our interview begins to wind down, I ask Bugg a simple question: Not everyone who picks up a guitar as a teenager attempts to write songs. Why did you?

“I was about 14 years old,” he says. “I was playing covers up until that point. And I thought, ‘All these songs I really enjoy playing have all been written by these people themselves. And some of those songs could make your day—could tap into how you were feeling at that particular moment.’ And I thought, ‘That is what I’d love to do—write songs that could help people or inspire people. Make somebody’s day. That would be the best thing in the world.’”

Before he hangs up the phone, Bugg tells me about the first good song he wrote. It was called “I See Her Crying”: “three chords, kind of a mixture of country and Buddy Holly and a bit of blues. That was when I realized I could take all my influences—everything that I heard or loved—and put it into one thing.”

There’s a video on YouTube of Bugg performing “I See Her Crying” at a tiny venue called The Maze, back in his hometown of Nottingham. It’s June 21, 2010. Bugg is 16: no record contract, no co-writers, no model girlfriend or Prada shoes. Just a Nike tracksuit and an acoustic guitar. He sounds exactly the same.