On October 28, long after pleading guilty to brawling with police inside the U.S. Capitol, James Mault and Greg Rubenacker filed near-identical documents from inside Pennsylvania’s Allenwood Low correctional facility.

“The United States District Court is a private for profit corporation. (It is not government owned),” read Rubenacker’s handwritten filing. “This court was created in 1871, along with the new form of government without the backing of the 1787 Constitution of the United States for America [sic]. This court was created 14 years after the 1787 Constitution.”

On these grounds, and what they described as other new legal revelations, Mault and Rubenacker requested their cases be dismissed. “If I knew about this information, I would of never plead guilty,” Rubenacker wrote.

The filings, full of pseudo-legal arguments, strange punctuation, and (in Rubenacker’s case) what appears to be blood, bear the hallmarks of sovereign citizen ideology. The sovereign citizen movement falsely claims that adherents are immune from large portions of the law, or that many government institutions are secretly illegitimate. The movement has a growing foothold in far-right communities, including among QAnon followers and members of an alleged plot to overthrow the German government who were arrested this month.

And increasingly, sovereign citizen legal tactics have found their way into cases related to the Jan. 6 Capitol attack. At least 11 defendants have deployed what experts describe as sovereign citizen talking points, either during their arrests, their trials, or even after pleading guilty.

“The sovereign citizen ideology is essentially that ‘You don’t have power over me, you don’t have control of me. The law doesn’t apply to me. The government is nonexistent,’” Christine Sarteschi, an associate professor of social work and criminology at Chatham University told The Daily Beast. “And if they could, they would essentially like to overthrow the government.”

Embracing Sovereign Citizenship

Sarteschi, who tracks the sovereign citizen movement, has documented nearly a dozen apparent adherents in Capitol riot cases. Most famous among those is Pauline Bauer, a Pennsylvania restaurant owner who made headlines for strange, sovereign-inspired antics in court.

Bauer is facing multiple counts of violent entry, disruptive conduct, and obstruction of Congress for her actions on Jan. 6, when she was filmed entering the Capitol and telling a police officer to “bring Nancy Pelosi out here now… we want to hang that fucking bitch.”

In court, she has claimed divine immunity from laws. “I do not stand under the law,” Bauer told a judge last year. “Under Genesis 1, God gave man dominion over the law.”

Strange though the argument was, it wasn’t Bauer’s invention. She learned it from Bobby Lawrence, a Pennsylvania man who’s built a following by preaching a fantasy legal theory that he describes as “American state nationalism.”

Like many orbiters of the sovereign citizen world, Lawrence insists his teachings are not related to the sovereign movement. “By and large everyone equates us to sovereign citizens,” he told The Daily Beast. “That’s how the public looks at it. They don’t realize there’s a difference between a national and a city-zen. City-zen. Municipal public servant. Break down the word: city, zen, ship. Municipal servant in admiralty.”

He’s correct insofar as sovereign citizenship isn’t real and no one can attain it. But his teachings, which urge followers to declare themselves as “nationals” of individual states (rather than of the U.S., which he believes is actually called the “several states”) is indistinguishable from other sovereign citizen practices.

Bauer tried following his advice for a time, spurning a lawyer in favor of representing herself—and likely resulting in more pretrial jail from a judge who stated that “I don’t want to lock you up... But you have made it clear that you feel you are above the law.”

In retrospect, Lawrence said, Bauer should have taken a more conventional legal route. “I’ve been studying on it for two years and I’ve learned so much in two years,” he said. But “knowing what I know now, I would’ve advised her to find a really good attorney and not helped her because it was too much of a heavy lift for her to do that.”

Bauer, who could not be reached for comment, has since begun working with a real lawyer and was released to her home in September. She has pleaded not guilty.

But while Bauer appears to be moving away from the practice, other Capitol riot defendants seem to have embraced sovereign citizenship in recent months.

James Beeks, a Broadway actor-turned-Oathkeeper, has espoused sovereign citizen talking points while on trial for his participation in the Jan. 6 Capitol riot. In a court filing last month, he announced that he was firing his public defender and choosing to represent himself “in Propria Sui Juris,” a favorite term of sovereign citizens acting as their own lawyers. He stylized his name as “:james beeks:,” a flourish the sovereign movement believes makes them immune from taxes, and signed the document with both the common sovereign sign of a fingerprint and his name, followed by “all rights reserved,” which sovereign citizens believe is an assertion of a person’s individual copyright. He has pleaded not guilty.

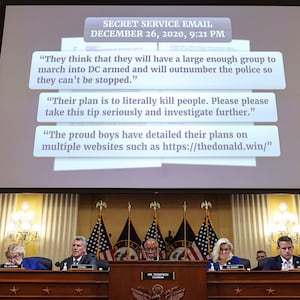

Howard Adams, a Florida man, fired his lawyers on Nov. 17. That same day, Adams was due in court—a last-chance appearance after he’d skipped a court date the previous week. But when a judge sent him a notice telling him to show up or face arrest, Adams sent the notice back, stamped with a red “notice for the record” stating that “I, by affidavit am a declared living American Sovereign standing with Treaty Law of God, do ‘REJECT YOUR OFFER TO CONTRACT’ to attend your ‘private bar guild matter’ for the following” reasons, including that he doesn’t believe he is a citizen, and that he believes the court is an admiralty court.

Adams, who has pleaded not guilty, was subsequently arrested. Lawrence, who told The Daily Beast he was not advising Adams, posted a message calling for a protest in Adams’ defense outside the courthouse. Approximately 50 people showed up, including a man who attempted to represent Adams, despite not being a licensed attorney.

A growing foothold in the far right

Even when they have a defense team, sovereign-aligned Capitol riot defendants sometimes spar with their lawyers.

In June, defendant Trevor Brown filed a motion to dismiss, apparently without his lawyer’s blessing. Brown wrote that he was filing “on my own without assistance” because he believed his attorney “works in conspiracy with the United States Attorneys.” (The lawyer, who has nevertheless gone on to argue Brown’s case, did not return requests for comment.)

Brown’s argument hinged on the sovereign claim that the government registers peoples’ names as trademarks, and that those names do not actually apply to them.

”The United States Attorney’s office for the District of Columbia has arbitrarily determined that the defendant as identified, TREVOR BROWN, is the same exact legal person as the State Citizen Trevor Brown without evidence or process to do so,” he wrote, adding that “Prisoner Trevor Brown, declares that I DO NOT CONSENT to being identified as the legal, or commercial or whatever kind of identity TREVOR BROWN truly is under any political, legal or commercial, process.”

Brown sat for a competency hearing last month and was released pending trial. He has demanded $6.86 million in damages from the government.

He’s not the only defendant using sovereign citizen arguments to demand vast sums from the government. Eric Bochene has pivoted between firing and un-firing his lawyers. While representing himself, he demanded $6 million for his troubles, plus other fees like $5 million for forced giving of bodily fluids. (Some sovereign citizen defendants in Capitol riot cases appear to have given bodily fluids willingly. Rubenacker’s filing contains what appears to be his thumbprint in dried blood, a sovereign hallmark. Bochene opted to sign his name with a thumbprint in less-biohazardous red ink.)

Before pleading guilty, Bochene also indicated that he wanted the court to pay him for invoking his name which, per sovereign citizen theory, he claimed was his personal property. “You (the court of plaintiff) created the bond in my name using a fictional ALL capital letter NAME or using a Name with a middle initial, either of which are a nom de guerre, and all of which I have a primary claim to,” he wrote. “Please use the bond to settle the charge or debt. As subrogee, I am entitled to all the creditor’s rights, privileges, priorities, remedies and judgements, unless rebutted specifically by someone with a higher claim.”

Defendant Bruno Cua has also fired his lawyers after citing sovereign citizen talking points, only to rehire them four days later in an about-face. A filing, made days after Cua’s in-court antics, alluded to the rift. “Recently, the attorney-client relationship between counsel and Mr. Cua has become irretrievably broken due to a fundamental disagreement regarding legal issues and a course of action,” the filing reads. He has pleaded not guilty.

At least one defendant’s lawyers have sought to exclude their client’s sovereign talk from the court record. Daniel Egtvedt, a Maryland man accused of assaulting police inside the Capitol, made a sovereign-flavored plea to a local sheriff after his arrest last year. While fighting extradition to D.C., Egtvedt wrote two letters to a sheriff in which he implied he was only a citizen of one state. “If you release me to federal agents at this moment you could place me as a political prisoner in a foreign land,” he wrote.

A police report from Egtvedt’s arrest is also peppered with references to maritime law, a series of laws for the open sea, which sovereign citizens falsely believe govern the U.S. “On February 16, 2021, Egtvedt was picked up at the detention center without incident and driven to D.C,” the report reads. “During the trip Egtvedt at one point asked an FBI agent what ‘port’ he was being taken to, and also made a reference to ‘maritime law.’ The agent told Egtvedt in response that he did not understand what he was asking.”

Egtvedt has pleaded not guilty. His lawyer, who did not return a request for comment, moved to exclude the letters from the court record.

Sarteschi, the Chatham University professor, as well as researchers at the University of Maryland's National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, have also identified sovereign citizen language in a bizarre filing by defendant Alan Hostetter.

Hostetter, a former police chief accused of conspiracy in the Capitol riot, filed a long, conspiracy-laden motion to dismiss last year. In the 82-page document, he claims a baroque COINTELPRO plot against him, “targeting him from the beginning of the Covid-19 lockdowns,” including via a man Hostetter believes was an FBI agent sent to harass him at a yoga class. In that document, he argues for a new convention of states. He has pleaded not guilty.

One defendant, Josiah Kenyon, does not appear to have cited sovereign citizen ideas in his criminal case, but invoked them during his arrest. During the Capitol riot, Kenyon assaulted a police officer while dressed in a Jack Skellington costume. Despite his conspicuous outfit, Kenyon avoided arrest for nearly a year, until police approached an off-the-grid trailer in the mountains outside Reno, Nevada. Kenyon’s wife refused to give her name or her husband’s, telling police it was “unconstitutional.” Kenyon’s children also spoke with what police described as sovereign citizen language. Kenyon drove away, but was soon arrested with a car full of weapons.

He pleaded guilty, as have other sovereign-inspired defendants like Mault and Rubenacker.

But despite their guilty pleas, the latter two defendants appear to have taken new heart in sovereign citizen legal theories. Both submitted filings in October, seeking to reopen their cases, on the grounds that the courts were invalid.

Mault even entered a second filing, criticizing a judge who’d called his filings sovereign citizen talk. “From the statements that the judge made in the order she seemed to have assumed that I have some type of belief or familiarity with the sovereign citizen movement, and some type of odd belief or missunderstanding [sic] about the 14th Amendment,” he wrote. “My intent for filing the motion had nothing to do with the issues she raised in her order.”

Self-described sovereign citizen or not, Mault is unlikely to find success with the movement’s tactics.

“Sometimes people say ‘why would anyone become a sovereign citizen? Why don’t they know that this doesn’t work?’” Sarteschi said. “I don’t think [sovereign citizen] do know. They think it works. They think that their strategy, their particular paperwork, their methodology is gonna make the difference.”