TOKYO—On Thursday morning, Japan’s deceptively dubbed “anti-terrorism” bill was steamrolled into law by its parliament, after the ruling coalition gutted standard legislative protocol, avoiding more embarrassing questions about the bill known as the “criminal-conspiracy law.” It stipulates 277 crimes that police can arrest people for planning, or simply discussing. Technically, because social media is covered in the legislation, even liking a related tweet or retweeting it could now be grounds for arrest on conspiracy charges.

Ironically, none of the 277 crimes have to do with terrorism, despite the name of the law. However, if you were planning to hunt mushrooms illegally or stage a boat race without a license—well think again, evildoers. You’ll be stopped in your tracks.

The essence of the law is simple: It allows law-enforcers to arrest and prosecute those who plan and prepare crimes even if those crimes are not carried out. There are 277 specific crimes that can be prosecuted for conspiracy, and possibly even more if the law is loosely interpreted.

However, as the contents were debated in the parliament, it became clear that the legislation was not only terrifying in the latitude it gives police but also terribly written. Ministry of Justice officials admitted that people could be arrested and convicted for conspiring to illegally hunt mushrooms (forestry laws) or go fishing. Often they were stumped for answers. Japan’s Lawyer Federation also pointed out that other terrible crimes covered under the law include copyright violations—such as copying sheet music, or a sit-down protest opposing the building of a condominium.

Of course, we all know that music teachers, mushroom hunters, and anti-condominium radicals are dangers to society, but do we need to proactively jail them? Yes, of course, we may need to. At least in Japan.

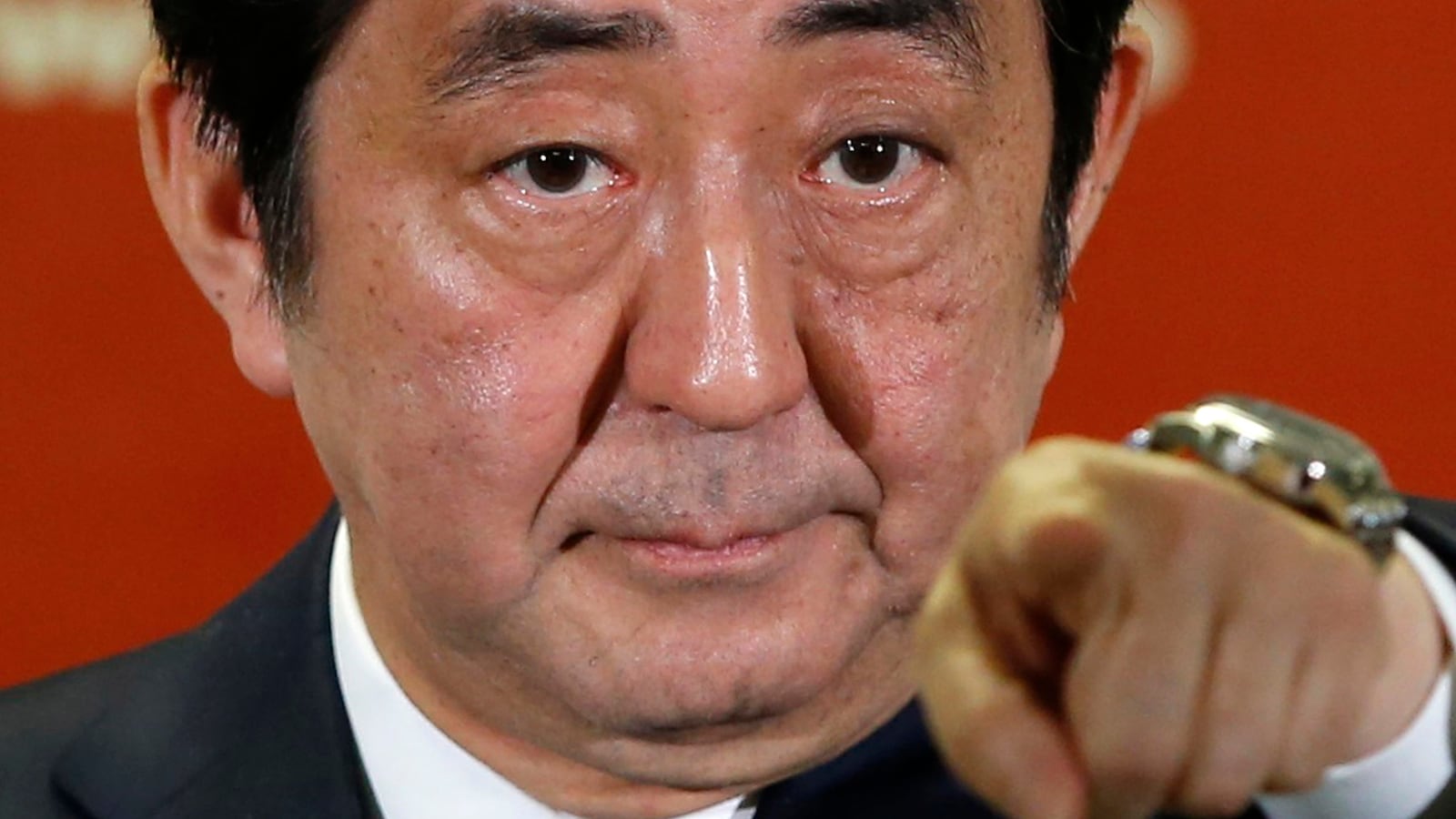

Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s administration shamelessly claimed the bill was necessary for Japan to comply with the United Nations Convention Against Transnational Organized Crime, a claim that U.N. experts ridiculed. The government then claimed it was needed to strengthen Japan’s counterterror measures before the 2020 Olympics. The legislation was originally dubbed the Criminal Conspiracy bill, but the name was changed to “Terrorism and Other Crime Preparations,” ostensibly to make it sound more palatable. The original bill had over 600 crimes. But as the Japanese Federation of Lawyers pointed out, “Even with a change in name, the bill is just as flawed and dangerous.” However, the rebranding did help get more favorable responses in public-opinion polls conducted after the bill was resubmitted.

In many other countries, empowering police to arrest people on such a wide range of pretexts might not be so bad, but in Japan authorities can hold a suspect for as long as 23 days, with no right for the accused to have a lawyer present before the decision to file charges. For those indicted, the conviction rate is close to 99 percent.

Japanese legal expert Colin P.A. Jones noted in an op-ed, “During this period, [the police] can question suspects from dawn until dusk, with limited access to a lawyer. Moreover, although a suspect may be arrested for one crime, it may be a pretext for investigating another, leading to further arrests that restart the detention clock. Thus, without conspiracy being added to the mix, Japanese law-enforcement authorities already have broad powers to punish people they don’t like without ever putting them on trial.”

In 2015, after police arrested Mark Karpeles, the CEO of failed bitcoin exchange Mt. Gox, on minor charges, he refused to confess to stealing its missing 650,000 units of the cryptocurrency (at current prices, around $16 billion). Police then kept arresting him on separate charges, in hopes he’d crack. Eventually he was arrested and indicted so many times the presiding judge chewed out prosecutors and ordered them to stop dragging out the detention.

If you think Japanese police won’t abuse their new powers, think again. They have a record of abusing the powers they already have. This includes arresting club owners for allowing dancing after midnight. In January, the Saitama police arrested three anti-nuclear activists on bizarre charges. The alleged crime: Sharing the costs of a rental van for visiting meltdown-devastated Fukushima, which the police decided was “operating an unlicensed taxi service.”

The Public Security Division of most Japanese police departments even has a slang word for the last resort in arresting a suspected radical: “korobikobou.” This essentially involves an officer bumping into a suspect and then arresting them for obstruction of police performance of duties (Article 95 of the Criminal Code) and holding them in detention for as long as possible, interrogating them at leisure.

Giving police an arsenal of pretexts to arrest anyone is a recipe for crushing civil liberties, as Joseph Cannataci, United Nations special rapporteur on the right to privacy, pointed out in his letter to the Abe administration warning of the dangers of the legislation. The new law is remarkably similar to the 1925 Peace Preservation laws, which the fascist government of Japan used to round up its critics, all communists, and war dissenters. When those laws were passed, just as they are now, the Japanese government claimed the laws would never be used to target ordinary citizens.

That was not the case.

The Abe administration, by the way, still classifies the pacifist and populist Japanese Communist Party, which has large popular support, as a “dangerous group”—the kind of group these new conspiracy laws will target. They’re about as dangerous as a schoolteacher. But at least the police will have some people to arrest.

The debate leading up to the passage of the bill had elements of dark comedy or political farce that induced both laughter and dumbfounded dismay. Not only was the discussion of mushroom hunting as funding for terrorist activity ludicrous, but it was revealed that the usage of forged postage stamps could also be grounds for prosecution. Terrorists: Put away those rogue postcards.

There was hardly a chance that the law wouldn’t be passed with the ruling coalition of the Liberal Democratic Party and Komeito having enough numbers to railroad the legislation into law, as they have been doing since 2013. There were massive protests by not just the usual leftover liberal hippies but students and young people as well. None of it mattered.

In the end, Abe’s ruling coalition resorted to the almost-unprecedented tactic of bypassing committee-level approval of the bill in the upper house, cutting off further debate, and thwarted all attempts to block the bill. Ren Hō, the leader of Japan’s opposition party, accused the government of ramrodding the bill to cover up its “Kake Gakuen problem,” which involves Abe’s alleged misuse of power in the licensing of a school.

Ren Hō jeered, “What’s the rush? You don’t want us to bring up the Kake Gakuen scandal again? The way the bill is being rammed into law seems to represent the government’s wish to hurry up and end the parliament session.”

Indeed the fight over the conspiracy law has at least temporarily slowed questions about the Abe administration’s own alleged conspiring—reportedly to block investigations into its own corruption, hide official documents, defame political opponents, and other scandals.

Abe cabinet officials also indicated Wednesday they intend to have the government employee(s) turned whistleblowers in the Kake Gakuen scandal arrested for violations of its civil servants act (disclosing confidential information). Understanding Japanese law, people can’t be arrested for conspiring to blow the whistle on malfeasance by the government. However, it can only be a matter of time before telling the truth is tacked onto the list or pre-crimes—or rather, conspiring to tell the truth. The best way to fight crimes is to make sure they never happen, of course. And that’s today’s minority report from Japan.