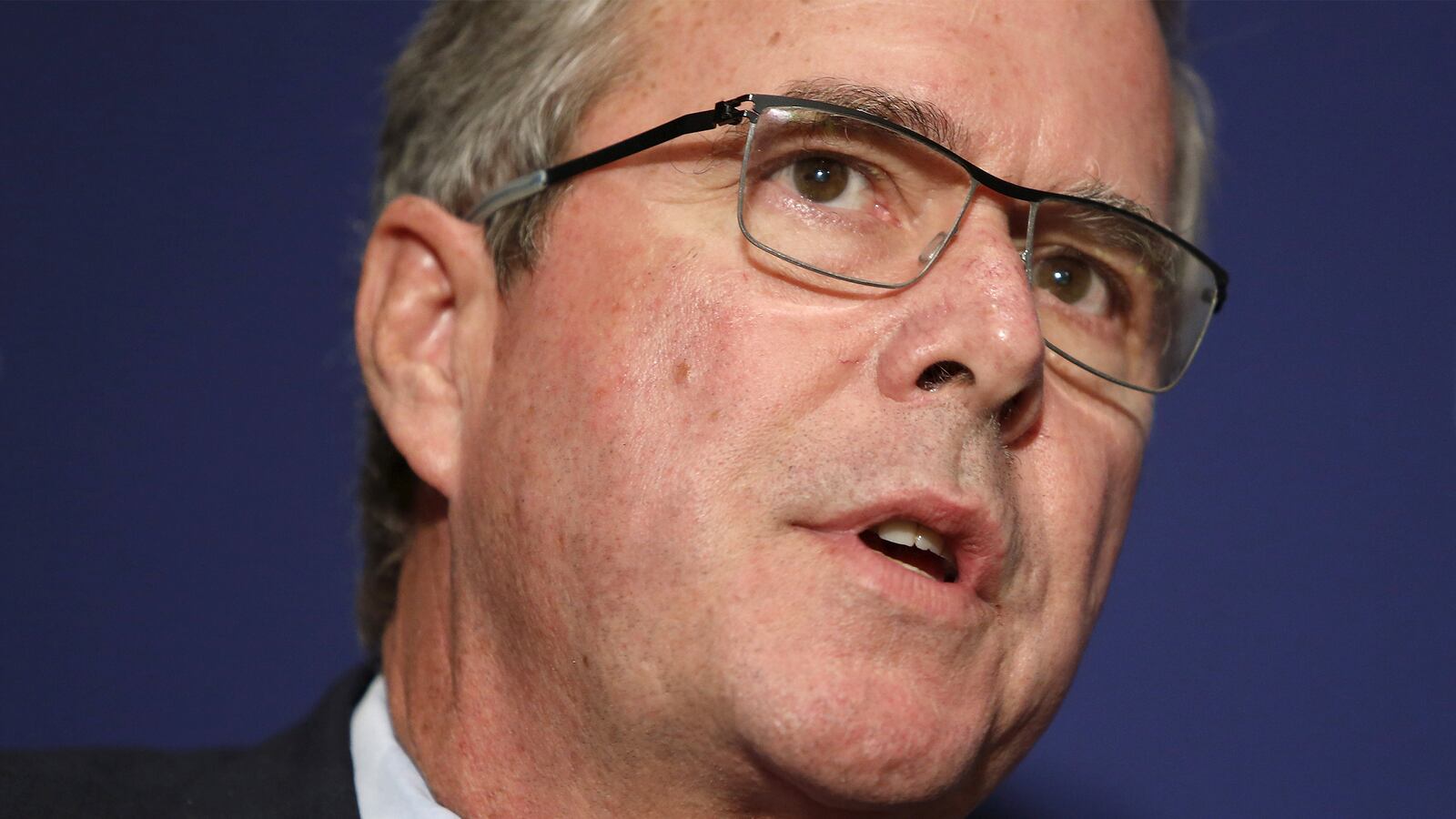

You could be forgiven for being a bit confused about what exactly Jeb Bush thinks about immigration.

Over the course of his political career, the former Florida governor has made statements about immigration policy that seem all over the map—he supports a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, he definitely doesn’t support a pathway to citizenship, he thinks we need more immigrants, he doesn’t plan to increase the number of immigrants coming in, etc. It can look a little dizzying.

But it isn’t.

Bush talks about immigration in three different ways and depending on how he’s talking about it, he says very different—but not necessarily incompatible things.

Let’s call the first approach non-wonk mode.

In non-wonk mode, Bush focuses on how big-picture immigration policy ought to work and how immigration impacts the United States in general.

In the latter chapters of Immigration Wars, a book he co-authored with Goldwater Institute attorney Clint Bolick, Bush writes in general about why he believes immigration is a social good and why the status quo hurts businesses and would-be citizens. He also makes the case for letting more immigrants come into the country legally.

“Left to its own devices and without increased immigration, America’s population is shrinking and aging,” Bush and Bolick write. “We need more immigrants to stem that debilitating demographic tide. We believe there will be less opposition to increased immigration if Americans perceive the need for and the value of immigration—which will happen if we fix our system so that most who enter our country add tangible value.”

In other words, Bush argues that we need more legal immigrants to preserve the entitlement system. But that’s a general statement, not a specific policy prescription.

Enter, Bush’s second approach: wonk mode.

Wonk mode is very different.

Sometimes, instead of making general statements (like, “in the future, if we are to have any labor force growth at all, immigrants will have to supply it,” as he writes in his book), he discusses his specific immigration policy proposal.

At the National Review Institute Ideas Summit last month, NR editor Rich Lowry pressed Bush on whether or not he wanted to let more immigrants come into the U.S. legally.

“I think the argument that [Wisconsin Gov. Scott] Walker would make, or at least that Sen. Jeff Sessions would make, is—it’s not an argument that it’s necessarily a zero-sum game,” Lowry said. “It’s a basic economic argument having to do with supply and demand. And if you increase the supply of low-skilled labor, of course low skilled wages are going to go down.”

“So who’s suggesting that?” asked Bush. “That’s the whole—that’s the false argument.”

Then Lowry pointed out that the Senate Gang of 8 immigration bill would have increased legal immigration levels.

“Although they talked the game of high skills, this will always increase low skills,” Lowry said. “But you want to decrease low skills?”

“I’m not a United States Senator, thank God, just for the record here,” replied Bush, to laughs. “I live in Miami, I’m outside of Washington. I’ve written a book about this. What I was describing is my ideas. My idea is to narrow the number of people coming for family petitioning and expanding the number of economic immigrants. You’re not increasing the number overall.”

That last sentence is the most important part.

Even though Bush writes in his book that he thinks we need more immigrants to grow labor participation rates and protect the entitlement system, his specific comprehensive immigration reform plan doesn’t intentionally increase the number of immigrants legally entering the U.S. every year.

Rather, it would decrease the number of immigrants allowed to enter because they’re related to a legal U.S. resident—for instance, it would keep the parents and adult siblings of legal U.S. residents from entering just because of that relationship—and give their spots to would-be immigrants with jobs lined up.

So as a general principle, Bush seems to back higher legal immigration levels. But the specific immigration policy overhaul that his book proposes doesn’t do that.

His final way of addressing the issue could be called “maybe mode.”

Bush talks about immigration policy changes that he could be open to but doesn’t actively advocate.

And that’s what happened on The Kelly File Monday night.

On the campaign trail, Bush has often touted the fact that he supports a pathway to legal status for the undocumented immigrants but doesn’t favor giving them citizenship.

He told Charlie Rose in 2012, however, that he would be open to letting those immigrants become citizens. Kelly pressed him on this, and he said that while his plan doesn’t call for a pathway to citizenship, he would be open to it if it was part of a deal that got him his other immigration priorities.

“I’ve said, as long as there—if that was the way to get to a deal, where we turned immigration into a catalyst for high, sustained economic growth, where we did all the things we needed to do in border security, where we narrowed the number of people coming through family petition and dramatically expanded a like kind number for economic purposes which will help us grow and help the median rise up, in return for that, as a compromise, sure.”

Then he continued with this: “But the plan in our book, the plan that I have suggested when I go out and speak, which is almost every day on the subject, I’m talking about a path to legalized status.”

So if Bush became president, a pathway to citizenship would be an option on the negotiating table.

It’s worth noting that many Democrats in Congress insist on a pathway to citizenship as a prerequisite for their support of any comprehensive immigration reform bill.

Jeb’s nuanced way of speaking about immigration reform sets him apart from his competition. Most (if not all) of the other Republican presidential contenders just talk about immigration in one way: opposition.

They oppose the president’s executive actions on immigration, so-called amnesty and any pathway to citizenship.

But they’re far less specific when it comes to how many legal immigrants they would allow into the country every year, how their ideal immigration policy would work, and what kind of compromises they’d be willing to make to get there.

Immigration could be the single most contentious issue for Republican primary contenders. And for many primary voters, it’s one of the most important. By talking about the issue in a variety of different ways, Bush has already distinguished himself from his potential competitors. It’s an open question as to whether primary voters and caucus-goers will think that’s a good thing.