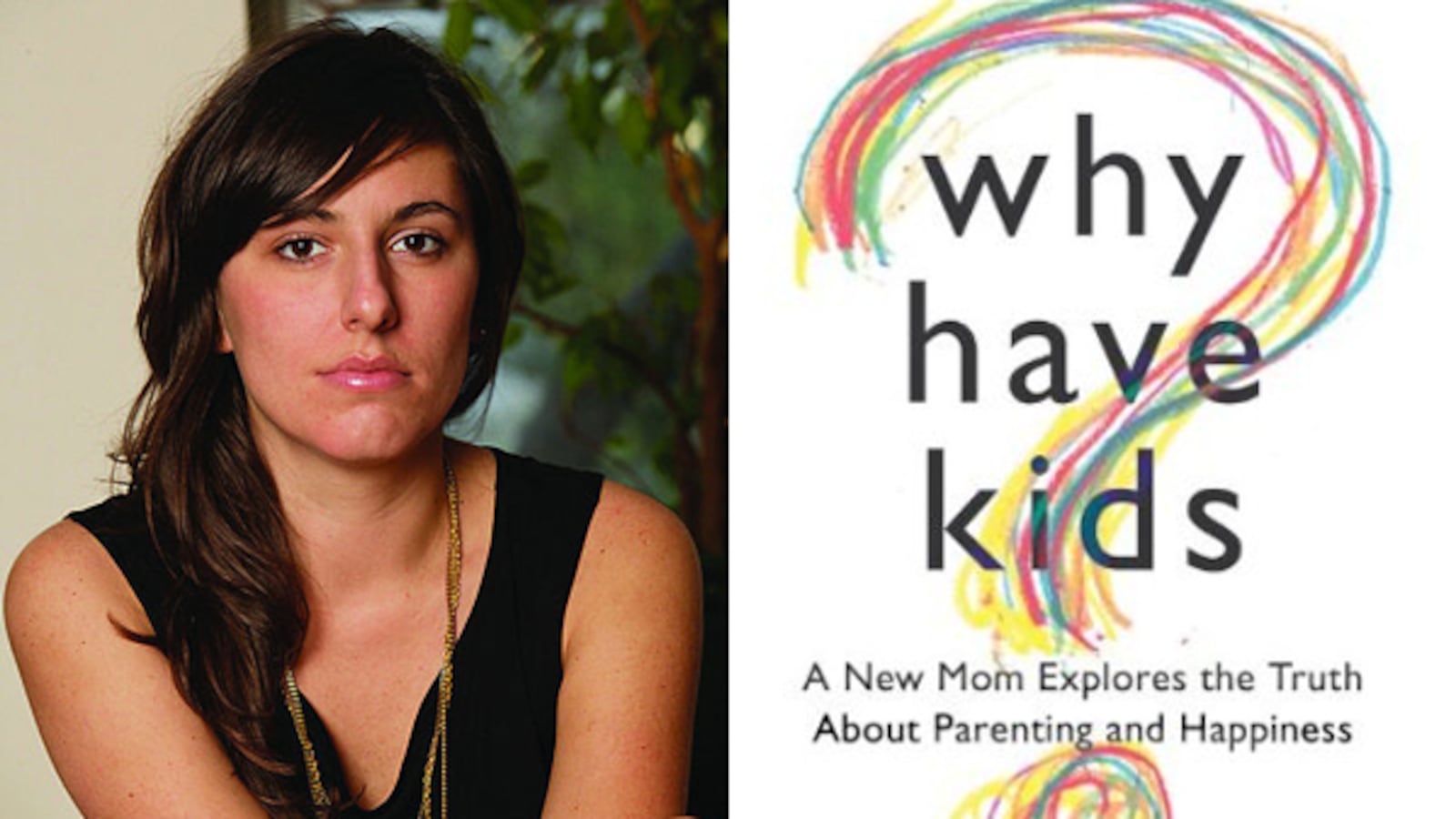

The title of Jessica Valenti’s new book Why Have Kids? has an undeniable appeal to women like me. Valenti, the founder of the website Feministing.com, has already skewered society’s emphasis on chastity in The Purity Myth, and analyzed and thoroughly debunked 50 different double standards in He’s a Stud, She’s a Slut. With her newest book, she aims to turn that critical eye towards motherhood, exploring the reality that being a parent is often more nuanced—with less joy, and more ambivalence—than society would have us believe, and, ostensibly, questioning why smart women would choose to have kids at all. When it comes to unpacking what it means to be female in America right now, she’s one of the smartest minds out there, and for those of us who are in our early 30s, relatively secure both professionally and financially, and yet ominously Without Child, this book is sure to beckon on the bookstore shelf.

While the conventional wisdom may have it that women—all women—want children, many of us, myself included, actually aren’t so sure about that. I love kids. When my 21/2 -year-old niece reaches up to hold my hand, it brings me incomparable joy. But I also witnessed my own mother’s struggle as she juggled the demands of running a small business with those of raising me. And I’ve watched friends’ marriages tested, their careers derailed, their concerns over money and space and nannies and schedules skyrocket with the arrival of their children. I love children. I do. But I also don’t have any illusions about their being easy, and I don’t feel incomplete without them. If I end up not having any at all, that would be fine with me. I think. Right?

Deciding to be agnostic about child-bearing—deciding, like me, not to make procreation a priority—doesn’t mean becoming immune to the onslaught of messages about the importance of motherhood. We are, after all, in an election season in which access to reproductive rights is a topic more polarizing and vitriolic than at perhaps any time in recent history. Last week, Ann Romney extolled the virtues of motherhood at the Republican National Convention, calling mothers “the best of America.”

This is also the year in which we saw a nude, ostensibly pregnant 63-year-old on the cover of New York magazine, a 26-year-old blonde breast-feeding her nearly 4-year-old son on the cover of Time, and a baby in a briefcase on the cover of The Atlantic—meant to illustrate Anne-Marie Slaughter’s argument that women can’t, in fact, have it all. None of those options seem, to me, particularly appealing, but they reinforce the message that there’s little that women won’t do in pursuit of the motherhood ideal: Give birth as a grandma! Breastfeed till college! Quit your job at the State Department to raise a troublesome teen!

Between all of that—not to mention incessant questions from meddlesome aunts and uncles and wannabe grandparents—the cacophony of voices can seem deafening. It can get so loud that it becomes difficult to silence our self-doubt, impossible not to think, at least on some level, that when we’re 80 and alone, we’ll regret not making different choices, not having done everything possible to put these hotly debated uteruses of ours to good use. It’s enough to make you wonder whether not having children means missing out on the most essential part of the human experience, and whether failing to procreate makes you somehow less of a person.

Which is why it would be so nice to hear a smart young woman like Valenti wrestle with these questions, too. Would having children change her sense of self? Would a baby come in between her and her husband? Would her friendships suffer with motherhood? Would there be tension between her identity as a feminist and her identity as a mom? Would she, like studies have shown, be suddenly saddled with more housework, a lower salary, a husband who doesn’t pitch in quite so much at home? And if so, what would she do about it?

Valenti has helped us wade through the morass before. She’s an astute observer and critic of popular culture, and has, through both her books and her blog, helped thousands of girls and women understand how societal pressure can affect what we want—and, more importantly, what we think we want. In The Purity Myth, she drew clear and convincing parallels between Girls Gone Wild and chastity balls—weaving them together into a thoughtful exploration of America’s obsession with female sexuality, and how the emphasis on virginity can be just as disempowering as promiscuity. It helped many of us cast a more critical eye toward the messages—both quiet and loud—we receive every day.

When Valenti got married, she explained her decision to wear only a simple gold band thusly: “The only purpose of an engagement ring is to show you ‘belong’ to someone, and your man makes bank.” This is a woman, in other words, for whom the decision to be a mother can’t have been without its complications. And, in fact, Valenti does wage a persuasive argument against it. In the first half of the book, titled “Lies,” she outlines studies showing that, contrary to the conventional wisdom, having children generally makes people less happy, not more. She likewise challenges the notion that being a parent is both the hardest and most rewarding job in the world, saying that parents just choose to believe that it is, because, “the truth is just too damn depressing.”

Valenti urges those who do become parents not to engage in the so-called “mommy wars,” urging fathers and mothers alike to acknowledge the occasionally mind-numbing minutiae of child rearing and refrain from judgment when it comes to things like breast-feeding and the merits of staying at home with the kids versus handing them off to a nanny. And she shrewdly examines the inequity of the fact that mothers are held to such a higher bar than fathers. “When dads know these intimate details of their child’s life, they’re considered heroes,” she writes about taking care of day-to-day logistics like having enough sanitary wipes and making appointments with the pediatrician. “When moms do, it’s standard.”

The problem is, she never convincingly argues the opposite point, which means she never actually answers her question—or my own. There’s no doubting what decision she made; it’s right there in the subtitle: A New Mom Explores the Truth About Parenting and Happiness. What we don’t know is how she got there.

The ultimate conclusion that Valenti comes to goes like this: “The truth about parenting is that the reality of our lives needs to be enough.” This line is repeated both in the book’s conclusion and its promotional materials. But it doesn’t tell us anything about whether or not to have children. It doesn’t actually tell us much of anything at all.

It’s also a line, and a book, that makes me think about what my friends have described as a lack of mental clarity experienced during their own pregnancies, and a fuzziness of thought that comes from the lack of sleep after having given birth. It reminds me of my own ambivalence when it comes to having children. And it makes it hard not to think that the book would have been much more convincing if she’d been asking the question—Why Have Kids?—not as a new mom herself, but as a young woman trying to decide whether or not to become one.