As the fate of Wisconsin’s primary volleyed between the state’s Democratic governor, its Republican-led legislature, and the Wisconsin Supreme Court, the man who appears set to win the election scheduled to take place on Tuesday has avoided taking a hard stance on the wisdom of holding the lone contest in April not to be postponed due to the coronavirus pandemic.

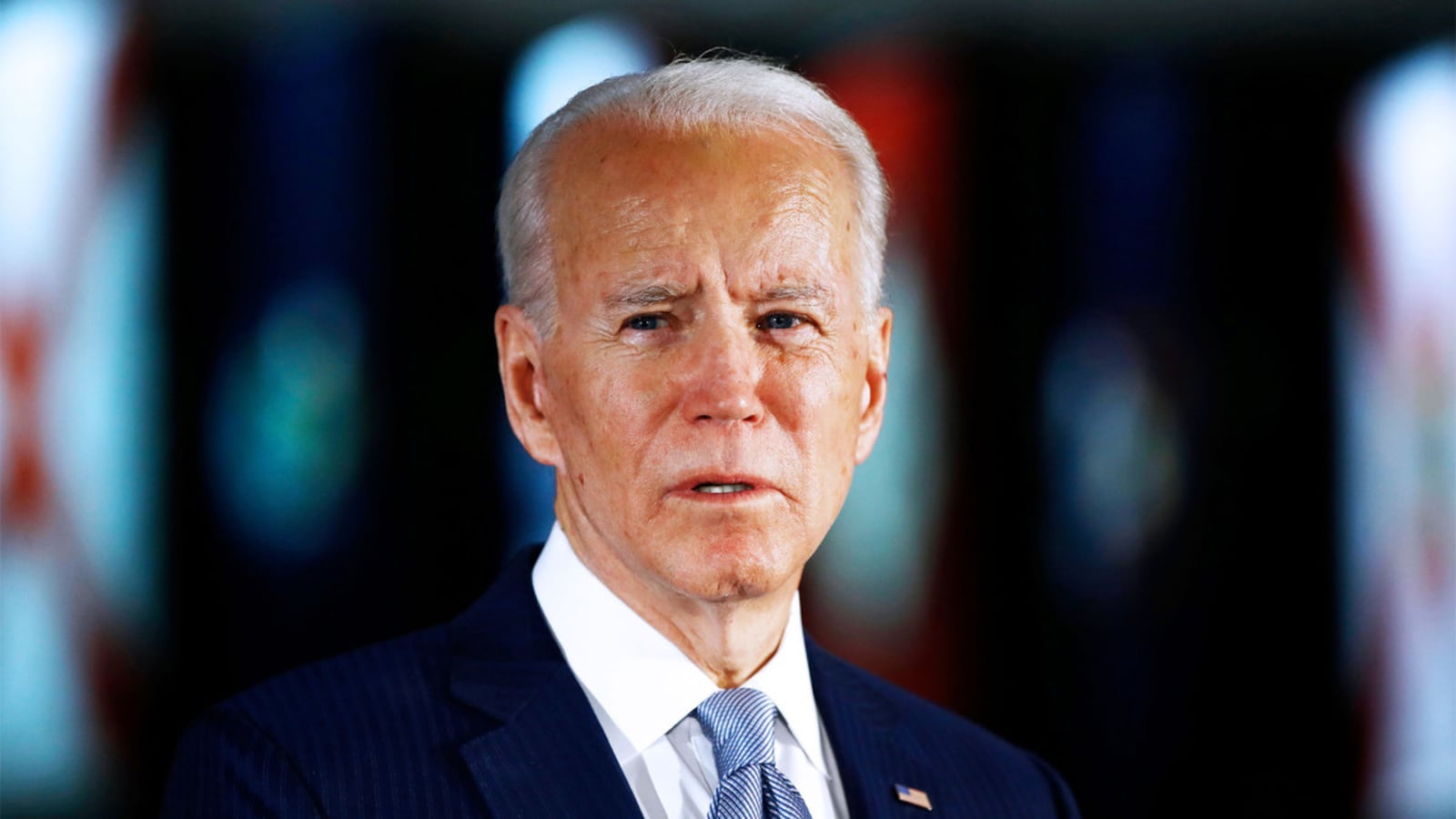

“There’s a lot of things that can be done; that’s for the Wisconsin courts and folks to decide,” former Vice President Joe Biden said last Thursday in a virtual press briefing, in which he insisted that in-person and mail-in voting could both be done safely—even though he considers the possibility of a national convention in the state to be a potential risk to public health.

“A convention having tens of thousands of people in one arena is very different than having people walk into a polling booth with accurate spacing with 6 to 10 feet apart, one at a time going in, and having the machines scrubbed down,” Biden said. “I think you could hold the election as well dealing with mail-in ballots and same-day registration. I think it could be done… but that’s for them to decide.”

Biden’s approach to the Wisconsin contest has put both himself and Wisconsin Democrats in an awkward position as county leaders painted a dire picture of what voting could look like in the middle of a pandemic. The party’s nominee-in-waiting has simultaneously floated the possibility of this summer’s newly rescheduled Democratic National Convention—also to be held in Wisconsin—going virtual to prevent the virus’ spread, while publicly insisting that Tuesday’s vote can go on even in the midst of a national public health crisis.

“I can only wonder if he’s completely aware of the situation on the ground in Wisconsin,” Kim Butler, the head of the Polk County Democratic Party, said of Biden not calling for a delay. “Because I don’t think if he was really seeing and hearing what was going on here that he would necessarily feel that way.”

But Butler, who lives in a red county and said the dynamics playing out on the ground in her area have shown her how difficult it can be to vote, worries that in-person voting Tuesday means that voters will get sick—and that fears of the pandemic will suppress the vote.

“My major fear is that people are going to get sick and possibly even die from voting tomorrow,” Butler said.

In Sauk County, the Democratic party chair said Monday morning she was focusing on getting absentee ballots returned. But in another sign of the times, she wasn’t actively encouraging in-person voting on Tuesday.

“For safety’s sake, we are not even asking people to go to the polls,” Sauk County Democratic Party leader Tammy Wood said.

Wood described the looming election as a moral dilemma.

“We can ask those voters to make sure those (absentee) ballots returned,” Wood said. “But in good conscience, we cannot ask voters to risk their lives and their families to go to a biohazard of a polling place and cast a ballot.”

Local elected leaders have echoed those concerns, with the mayors of 10 Wisconsin cities—representing a combined fifth of the state’s population—urging for the election to be postponed in the interest of public safety.

“We implore you to implement all emergency measures necessary to control the spread of COVID-19, a communicable disease,” said the letter, addressed to state Department of Human Services Secretary Andrea Palm and signed by the mayors of Milwaukee, Green Bay, Madison and Racine, among others. “Specifically, we need you to step up and stop the State of Wisconsin from putting hundreds of thousands of citizens at risk by requiring them to vote at the polls while this ugly pandemic spreads.”

The Biden campaign did not respond to questions about those concerns, which have informed a chaotic leadup to Tuesday’s election. One week before the primary, Gov. Tony Evers declared that “if I could have changed the election on my own I would have but I can’t without violating state law,” before issuing a Hail Mary executive order on the eve of the election to suspend in-person voting after the state legislature refused to reschedule the vote.

In a statement accompanying the last-ditch order, Evers admitted that “there’s no good answer to this problem,” before pinning the confusion on the Republican-led state legislature’s failure to “do its part” to ensure public health during the primary.

“But as municipalities are consolidating polling locations, and absent legislative or court action, I cannot in good conscience stand by and do nothing,” Evers wrote. “The bottom line is that I have an obligation to keep people safe, and that’s why I signed this executive order today.”

Even as Republican leadership in the state house immediately announced their intent to challenge the order in front of the Wisconsin Supreme Court, city and county leaders issued their own orders blocking in-person voting.

Later on Monday, the court issued a 4-2 ruling that Evers cannot postpone in-person voting, throwing out the executive order.

The confusion has put the chaos of Iowa’s caucus night to blushing shame—and has Democrats frustrated that the only person calling for in-person voting to be postponed is the man who appears destined to lose big in Wisconsin.

“People should not be forced to put their lives on the line to vote,” Sen. Bernie Sanders said in a statement on Wednesday, calling on the state to join 15 others in rescheduling the contest. By the end of that same day, the Wisconsin Democratic Party chairman had also tweeted out the state party’s support for the contest to be pushed back.

But Democratic efforts to keep in person voting from happening Tuesday fell flat despite concerns about widespread poll worker shortages across the state. A lack of workers in some places, and fewer polling places, could lead to the kind of long lines that voters most fear finding themselves in during the health crisis.

Officials have been clear about the challenges awaiting the state on Tuesday, including in Milwaukee. In a statement posted on its Facebook page on Friday, the City of Milwaukee Election Commission warned that “severe shortages in election workers,” meant 180 voting places have been whittled down “into five voting centers.”

“This change is in no way an endorsement of this state’s dangerous decision to move forward with the April 7 election, but is instead a necessary step to provide in-person voting,” read the post.

Absentee ballots have taken on a great deal of significance in the contest, though legal wrangling over specifics has added to the confusion that troubles onlookers, as has the announcement on Monday afternoon by the state elections administrator that the state will not be able to release election results for nearly a full week.

“It’s almost overwhelming as chair to try to keep the airplane flying when pieces are falling off every day and flight plans are changing every day,” Walworth County Democratic Party Steven Doelder said.

Complicating the Tuesday contest further is the fact that a major state Supreme Court seat is on the line, a race that President Donald Trump has weighed in on. Democrats in the state fear that low turnout could hamper their chances at that crucial seat. Local races are also on the ballot. Asked by a reporter during a coronavirus task force Friday about Wisconsin, the president launched into a lie-laden response about mail-in voting.

“I think a lot of people cheat with mail-in-voting,” Trump told reporters Friday. “I think people should vote with ID, voter ID. I think voter ID is very important. And the reason they don’t want voter ID is because they intend to cheat.”