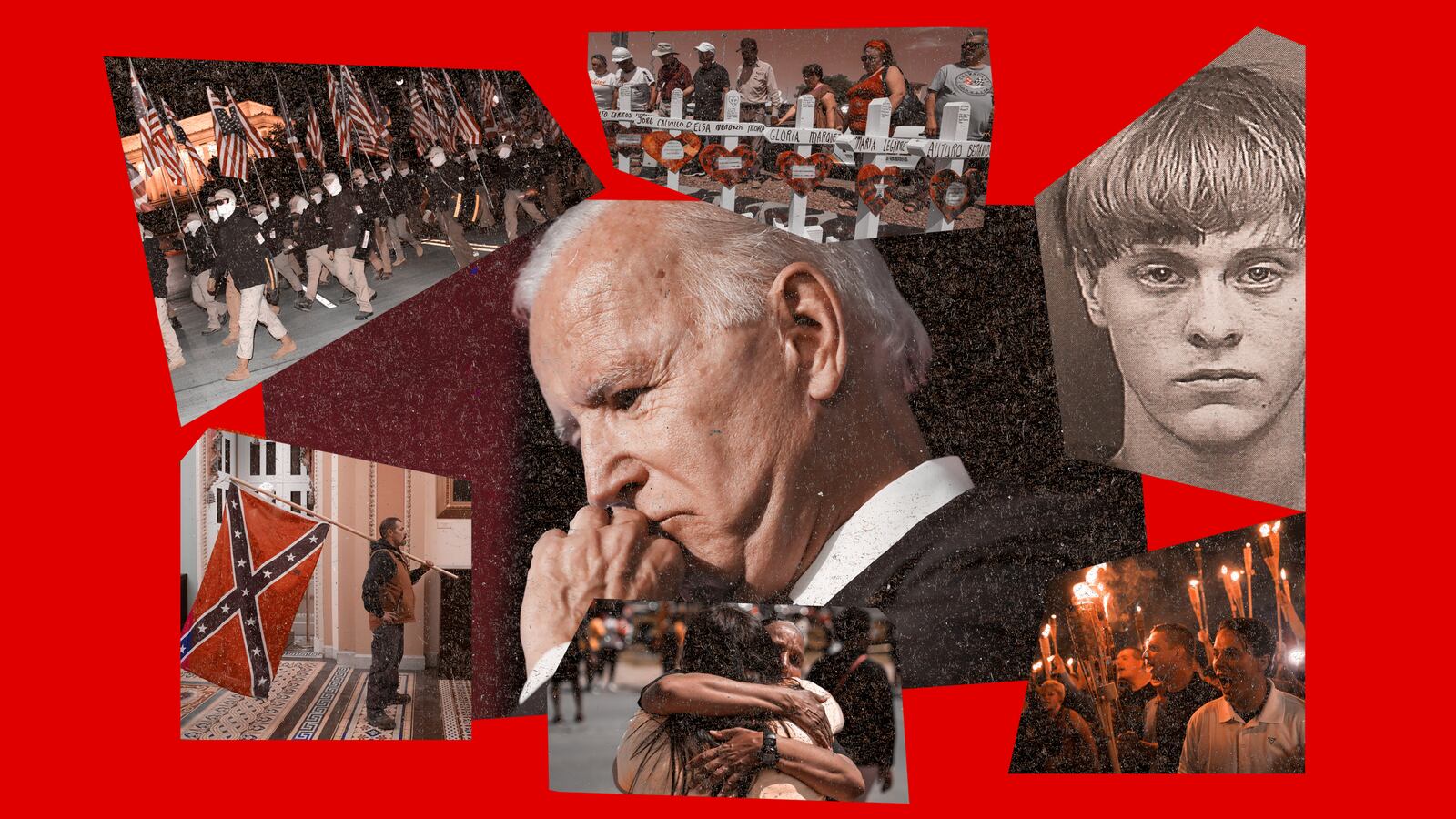

After the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol made clear the stakes of neglecting homegrown extremist movements in the United States, President Joe Biden appeared to have the greatest opportunity in decades to meaningfully combat domestic extremism. But nearly 18 months in, the murder of 10 people in Buffalo by an 18-year-old white supremacist is the latest violent demonstration of the administration’s limited ability to combat far-right terrorism—and, longtime foes of racist extremism say, its mixed success in fully implementing strategies to address the root causes of radicalization.

“In the wake of a tragedy, we have to keep the pressure on,” said Susan Corke, director of the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Intelligence Project, which monitors the radical right. “There’s a lot of things that could be done that are already kind of initiated, they just need to take them further. It’s about the political will and commitment to see it through.”

Biden’s vow to dismantle white supremacism was the centerpiece of his campaign to “restore the soul of America,” a campaign that was inspired, in part, in the aftermath of the white supremacist “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, which left three people dead in 2017.

“White supremacy is a poison,” Biden said on Tuesday during an appearance in Buffalo, where three days earlier a gunman had shot 13 people—11 of them Black—in a local grocery store. “It’s a poison running through our body politic, and it’s been allowed to fester and grow right in front of our eyes.”

“No more,” Biden pledged. “We need to say as clearly and forcefully as we can that the ideology of white supremacy has no place in America. None.”

But the surge of white supremacist violence that first began nearly a decade ago shows little sign of slowing down. Of 450 murders committed by political extremists in the past 10 years, the Anti-Defamation League has found that far-right perpetrators were responsible for three-quarters of those deaths. Last year, that number was close to 90 percent—with nearly half committed by white supremacists.

Since its outset, experts in studying and combatting white supremacist extremism told The Daily Beast, Biden’s administration has followed through on several of his promises to recommit the federal government to pursuing racist extremism, a major departure from the administration of President Donald Trump.

“The shift in tone and prioritization of these issues could not have been more dramatic compared to the previous administration,” said Ryan Greer, director for program assessment and strategy at the Anti-Defamation League, “and they acted pretty swiftly to take on some of the challenges.”

In June of last year, the administration released a National Strategy for Countering Domestic Terrorism, styled as a comprehensive strategic guide for federal agencies to prevent recruitment by domestic terrorist organizations. The strategy was organized around four pillars: sharing intelligence about domestic terror threats; preventing recruitment into extremist groups and movements; disrupting terrorist activity before it leads to violence; and addressing the root causes of radicalization to reduce extremism long-term.

Some of those priorities have been advanced relatively quickly. Last year, the Department of Homeland Security created a domestic terrorism branch within its Office of Intelligence & Analysis to help share intel on extremist threats with state and local law enforcement. DHS also launched a new Center for Prevention Programs and Partnerships (dubbed “CP3”), intended to support community-based initiatives to stop radicalization before would-be extremists become violent.

“It is definitely a paradigm shift,” said Randy Blazak, an Oregon-based sociology professor and hate crime researcher. Blazak, who won a grant under the CP3 program to develop community strategies for addressing violent extremism based on the model of public health, told The Daily Beast that DHS’s community-based model for curbing white supremacist violence has found success in other anti-crime initiatives like violence interruption.

That strategy, in which “credible messengers” close to potential violent offenders help curb them from making dangerous or deadly decisions, has found some success in combating gang violence, which Blazak said is often just a different form of extremism caused by social alienation.

“How do you use credible messengers—in this case, former gang members—when things are getting hot to take those guys and take them for a walk around the block to cool things down and de-escalate?” Blazak said. “So we’re using that contagion model of violence to look at how we can de-escalate right wing extremism.”

But those who have been worked to address white supremacist violence—and have even helped come up with blueprints for the government to do the same—say that other strategies haven’t yet been implemented, or even released in some cases,

Greer pointed to the State Department, which was congressionally mandated in the National Defense Authorization Act for the 2021 fiscal year to develop a strategy for “countering white identity terrorism globally.”

The strategy, which required conducting an assessment of the global threat of white supremacist terrorism and creating a process for engaging with foreign governments to limit the spread of white supremacist extremism online, is vitally important in the fight against far-right extremism, which has increasingly found a global audience. White supremacists often crib from overseas inspiration, including the perpetrator of the Buffalo massacre, whose 180-page manifesto was largely plagiarized from the one written by an Australian man who murdered 49 people at two mosques in New Zealand in 2019.

But as far as anyone can tell, the strategy to address that reality doesn’t yet exist.

“This is a transnational threat—there’s connectivity globally,” Greer said. “The U.S. Department of State supposedly created a strategy to counter global white supremacy, but as far as we know, they’ve not released that strategy, so we don’t know if it’s good or not, qne as far as we know, they've not asked for any resources to implement that strategy.”

The State Department did not respond to a request for comment about its progress in drafting its strategy on white supremacist extremism, or what that strategy entailed.

Meanwhile, some of the most powerful tools for addressing racist extremism at home are the responsibility of Congress, which has demonstrated mixed dedication to passing funding and legislation for the effort.

On Thursday, the House of Representatives passed the Domestic Terrorism Prevention Act, which would form dedicated domestic terrorism offices within the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Justice and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, each of which would be tasked with monitoring and investigating domestic terror activity. But the nearly party-line passage of the bill bodes poorly for the bill’s futures in the Senate.

Funding, too, has been a major issue, said Greer, who noted that the CP3 programs have just $20 million a year in grant programming intended to support and study prevention efforts.

“$20 million is far too little,” Greer said. “The prevention programming is woefully underfunded, as are the programs to evaluate those programs. So researchers to see what works in those programs. They have the strategy out there, and so the question is, what has been done to actually implement that strategy?”

The partisan nature of that gridlock also highlights the more systemic difficulties in combating white supremacist extremism—only a single Republican, Rep. Adam Kinzinger of Illinois, voted for the Domestic Terror Prevention Act, and Rep. Liz Cheney of Wyoming has accused the Republican Party of enabling “white nationalism, white supremacy, and antisemitism” nationwide through the embrace of conspiracism and rhetoric about the “Great Replacement” of white Americans by immigrants and Black people.

“White supremacy is getting into the living room of millions of people around the country every night,” Corke said. “We can’t make light of the fact that the far-right media ecosystem is amplifying, is normalizing, what were once really dangerous fringe ideas.”

But beyond issues of funding and slow-walked implementation of government strategy, Blazak said, is the lack of emphasis on the damage that white supremacist violence has done to minority communities around the country—and the risk of extremist violence begetting more violence down the line.

“Some people are going to drop out, some people are going to become very socially active, and people are going to take that rage to some very ugly places,” Blazak said, “including violence.”