In August of 2015, I caught a glimpse of Michael Flynn’s future in a Brooklyn federal courtroom.

It was at the sentencing of an Albanian man named Agron Hasbajrami on charges of material support for terrorism.

Hasbajrami, like Flynn, had a circuitous path towards his sentencing. Like Flynn, he had been caught on a wire. And, like Flynn, he pleaded guilty, then brought in a new attorney and sought to convince a judge to let him withdraw his guilty plea.

The judge in Hasbajrami’s case, a plainspoken former prosecutor named John Gleeson, had been patient through this years-long process.

Gleeson’s docket was filled with accused terrorists. And these cases were rife with allegations of government misconduct—coercive interrogations, abuse of FISA warrants, torture by client states.

Terrorism cases, particularly in New York after 9/11, brought out emotions in the courtroom. Defense attorneys expressed exasperation with the sprawling powers of the national security state. Federal prosecutors shouldered the thousand-pound pressure of keeping terrorists off the street.

Gleeson had a gift for listening. To foreign defendants describing the Kafkaesque experience of being rendered to solitary confinement in the United States. To young prosecutors pushing for the harshest sentences allowed under the law.

He also knew when to cut people off—and remind them that this was his courtroom and that he was the judge.

On this day, Gleeson caught the defendant in a lie. And, rather than let it pass, he added a year to his sentence.

“The last year of your sentence you can chalk up to that statement, Mr. Hasbajrami,” he said when he delivered his sentence.

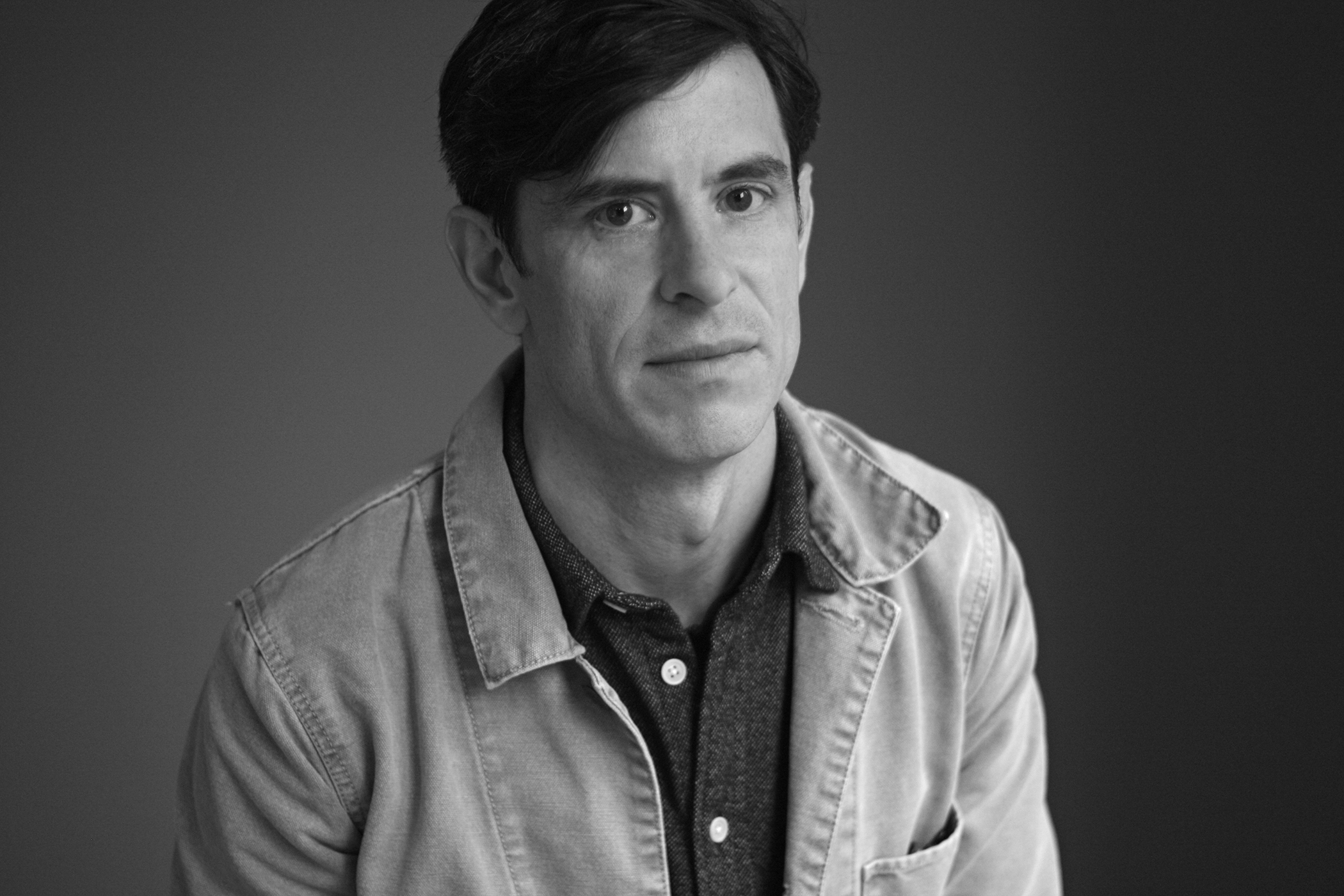

On Wednesday, D.C. District Court Judge Emmet G. Sullivan appointed Gleeson, who retired from the bench in 2016, to weigh in on Michael Flynn’s case. He was given two tasks: to argue against the government’s effort to throw out the criminal case against Michael Flynn; and to make a determination whether Flynn perjured himself and should face potential imprisonment for doing so.

“He doesn’t suffer liars and doesn’t suffer people trying to avoid the system,” said Karen Greenberg, director of the Center on National Security at Fordham University School of Law.

Gleeson’s decade as a prosecutor was marked by an almost Faustian bargain: the decision to take on self-professed murderer Sammy “the Bull” Gravano as a cooperator against John Gotti. The rival Southern District had pushed to take the case, but the head of the Justice Department’s Criminal Division—Robert Mueller—gave it to the Eastern District. In 1992, Gleeson secured the conviction against Gotti — who’d earned the nickname the Teflon Don after winning acquittals in his previous three trials — and, with that, a bit of immortality among organized crime prosecutors.

Two years later, at the age of 41, Bill Clinton appointed him to the federal bench, in the Eastern District, where he served for 22 years.

As a judge, Gleeson was difficult to pin down. The Eastern District is stacked with judges who take a dim view of the war on drugs, and have pushed to mitigate the collateral consequences of federal convictions. But while Gleeson was concerned by the “excessive severity” of the federal system, he isn’t easily characterized as a reformer. He ruled in favor of Bush administration officials sued by Muslim men detained after the 9/11 attack. And he later pushed a model to forgive federal convictions.

Throughout his time on the bench, Gleeson adopted a self-effacing approach. He never wore a robe. And he always entered the courtroom from chambers without a knock. As a prosecutor, he played basketball with the federal marshals who worked the courthouse. (“He was actually pretty good,” a former marshal recalled.)

District courtrooms in New York are often waystations for the ambitious and powerful, and Gleeson’s courtroom drew the Eastern District’s most aggressive and overachieving young prosecutors looking to make their names.

Many of these prosecutors did just that: Shreve Ariail went on to serve as deputy general counsel for litigation and investigation at the CIA; Seth Ducharme took the job as counselor to the attorney general then principal associate deputy attorney general; and Zainab Ahmad moved to Main Justice where she joined Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s team and, as it turned out, helped win the conviction of Michael Flynn.

After the Justice Department moved to dismiss the charges against Flynn, Gleeson penned a Washington Post editorial reminding readers that the decision to drop a case doesn’t belong to Attorney General William Barr, or a line prosecutor acting on his behalf. It belongs to the judge overseeing the case.

Judge Sullivan’s order to appoint Gleeson came the next day, after what had, otherwise, been a pretty lousy week for separation of powers.

First, the Justice Department had moved to dismiss its own case against Flynn on Monday. On Tuesday, a majority of Supreme Court justices seemed skeptical of arguments that the president, or his financial records, should be subject to subpoenas by Congress or a grand jury. Then, on Wednesday, new acting director of National Intelligence Richard Grenell—who has not been confirmed by Congress—chummed the waters of the 2020 election with a laundry list of Obama officials involved in unmasking Flynn’s identity from intelligence reports following the election, including Vice President Joe Biden.

Before the pandemic, it seemed that the Trump administration’s most irreducible legacy would be in the courts. This president has waged a quiet but successful effort to reshape the federal bench in the image of the Federalist Society, with conservative judges dutiful to the notion of executive power. The irony is how unsophisticated President Trump is when it comes to measuring the quality of judges. He has one brutally simple metric: whether they rule in his favor or not.

The unraveling of the Flynn prosecution is only the latest challenge to the judiciary—yet, it has an almost allegorical quality in the era of COVID-19. There are only bad choices for how to resolve it. On the one hand, there’s Attorney General Barr’s bald, deliberate campaign to rewrite the history of Russian interference in the 2016 election. On the other, an ugly, ham-handed, politically tinged FBI investigation in the wake of an election. Either path leads to the same place. The recognition that the institutions that are meant to protect our body politic have been infected with corruption.

This is not the perennial sickness that we’ve come to accept as a feature of our federal justice system—the onerous sentencing guidelines, the outsize power of prosecutors, the revolving door between the Justice Department, the media, and the private sector. This is a virulent strain that threatens the balance of powers in our government. But as a nation, we’re unable to come to a consensus on the diagnosis, let alone how exactly it should be treated.

The appointment of John Gleeson is a step in the right direction. It doesn’t ordain an outcome but guarantees a level of integrity to the process.

As David A. Schulz of Yale Law School’s Media Freedom and Information Access Clinic said, Gleeson is “smart, fair-minded and deeply committed to the rule of law.”

That doesn’t bode well for those who see the law as an extension of politics and truth as something to be defined by the powerful.