PARIS—“Oh, you weak, beautiful people who give up with such grace. What you need is someone to take hold of you—gently, with love, and hand your life back to you,” a woman’s voice intones at the beginning of the song that many in France consider the very best in the very long repertoire of Johnny Hallyday.

And if you listen to it, and especially if you watch the 1985 video, as the singer rides the rails and hitchhikes through rural America, you might think “Quelque chose de Tennessee” (“Something of Tennessee”) is about a state where Nashville’s the capital. But, no. The song’s not a tribute to country, but to literature. The lines at the beginning are from the play “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” and the title refers to the author, Tennessee Williams.

That is, as Johnny was, just so very French.

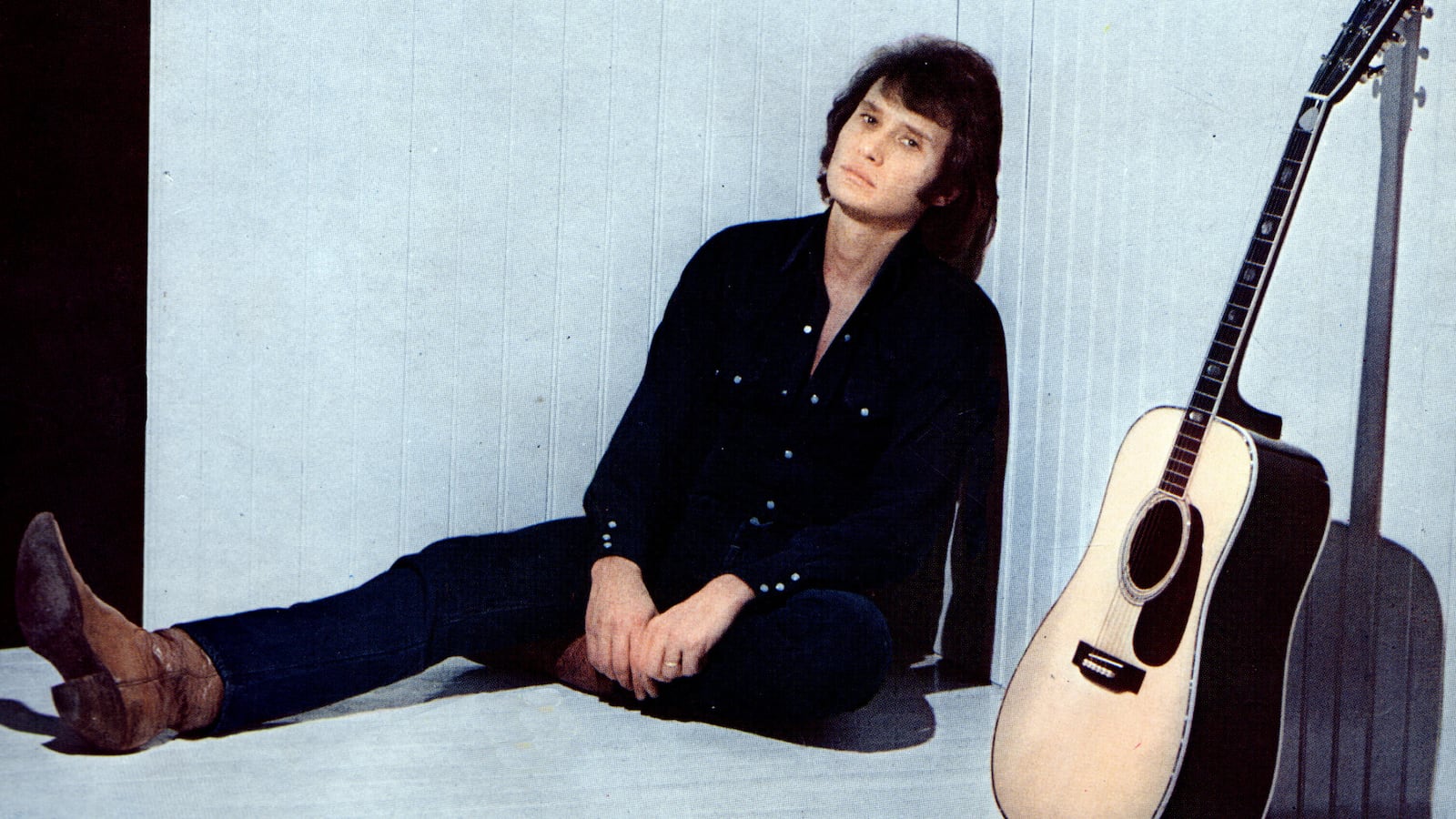

He was the “king of rock” here—but only here—a hip swiveling, leather-clad Gallic answer to Elvis Presley who shook up his home country’s music scene with American-style rock-n-roll and bad-boy antics.

Hallyday, who died Wednesday at the age of 74 after battling lung cancer, had an enduring musical career that spanned six decades. And up until the end, his countrymen considered him less a washed-up rocker than a national treasure and cultural icon.

“He was cemented in the French imagination like a living national monument,” Marc Lambron wrote in the French daily Le Figaro beneath a headline that referred to the singer as “the last idol of France.”

Jean-Phillipe Léo Smet was born in Paris on June 15, 1943 to a French mother and a Belgian father, who split shortly after his birth. He was raised by an aunt and two cousins—professional dancers who brought him along on tours throughout Europe—and developed an early taste for show business. One of his cousins married an American with the stage name “Haliday,” which Smet adopted with a slight misspelling.

Among Hallyday’s greatest influences was “The King” himself. A showing of Presley’s 1957 film "Loving You" at a local movie theater had a profound impact on the teenage Hallyday, who began taking acting, dancing, and singing lessons.

Hallyday started performing at a local Paris rock venue, and signed his first record deal at sixteen. His early specialty was French-language cover versions of famous songs by American crooners Eddie Cochran and Presley, among others. His American-style rock music and sexualized, Presley-like dance moves caused a sensation in France, where the demure French chanson ruled. By the early ‘60s, frenzied young fans crowded his concerts. The blond-haired blue-eyed Hallyday had become a bonafide musical sensation and, according to the French press, “a corrupter of French youth.”

Even Edith Piaf reportedly swooned over the hot young pop star. In his autobiography Dans mes yeux (In My Eyes) Hallyday recounts an encounter with the then-middle-aged Piaf at a restaurant when he was still in his teens.

“I was sitting beside her and, in the middle of the meal, I felt her hand climbing up my thigh,” Hallyday writes. “I hesitated. Then I left and ran away from there. I ran away from Piaf… I couldn’t see myself in bed with her. As far as I was concerned, she was an old woman.”

Over the years his style became more eclectic, comprising everything from French ballads to blues to country. Hallyday went on to sell over 100 million records and performed before legions of besotted fans, including a 2001 gig in front of the Eiffel Tower that drew some 600,000 people. His popularity in France was such that in 1966 Jimi Hendrix opened for him at one of his shows. Although known first and foremost as a musician, he also appeared in several films, most notably French auteur Jean-Luc Godard's 1984 Detective and more recently in Johnnie To's 2009 revenge flick, Vengeance.

In true rocker fashion, Hallyday’s cyclonic personal life made headlines as much as his music. He married five times, survived a near-fatal motorcycle accident, and attempted suicide at least once. He appeared on the cover of the French tabloid Paris Match dozens of times, and spoke candidly to the press about his battle with drugs and alcohol—“I need cocaine to get out of bed in the morning,” he once quipped to Le Monde. Rather than putting his fans off, his openness was endearing and such vulnerability made him appear more accessible to the everyman. Indeed, a headline in Le Monde Wednesday referred to Hallyday as “a sort of ordinary hero.”

Although he dreamed of a career in the U.S., Hallyday failed to win the hearts of American audiences. While his style may have been innovative in France, it wasn’t especially original in the actual birthplace of rock 'n' roll. Moreover, Americans tended to prefer the classic French chanson, and Hallyday’s gravelly-voiced rock songs were outside the confines of what Americans considered “French” music. America may not have loved him, but he loved America, spending many years in Los Angeles and ultimately growing to enjoy the anonymity afforded by being legendary only within the borders of his own country.

"I am not 20 years old any more,” he said in an interview with The Independent several years ago. "Perhaps, I'm a little tired of playing Johnny Hallyday. I want to be Jean-Philippe Smet again.”

Back in France, however, he was and always would be “Johnny”—a beloved icon whose passing has touched off a wave of national mourning.

News of the singer's death dominated media headlines all day Wednesday, and tributes to Hallyday have flooded social media. Trending topics on Twitter included the hashtags #JohnnyHallyday and #RIPJohnny with everyone from intellectuals to fellow musicians to politicians paying their respects.

“France is mourning a great artist,” former President Nicolas Sarkozy said in a statement. “Johnny will leave a void that no one will ever be able to fill.”

In Marnes-la-Coquette outside of Paris, dozens of fans converged outside of the singer’s home to place flowers or candles on the pavement.

“My entire youth has gone with him,” Michelle, who had followed the rocker’s career her whole life, tearfully told Le Parisien. “I am almost his age. He is a member of my family who accompanied me through my joys and sorrows… He really loved his public.”

For those who didn’t grow up with Hallyday or hadn’t even heard of him until fairly recently, such acute grief over the pop star can seem perplexing at first. But Hallyday clearly resonated with France’s national consciousness. He was a rocker, but, in his way, a comforter as well. He was someone whose music and persona could take hold of you—gently, with love, and hand your life back to you. And his death has brought the country together, at least for a moment, to mourn the end of an era.

“I am in shock! Johnny is a monument! He is France!” fellow French icon Brigitte Bardot said in a statement, echoing the sentiments of heartbroken fans. “An epoch has disappeared forever with him…”