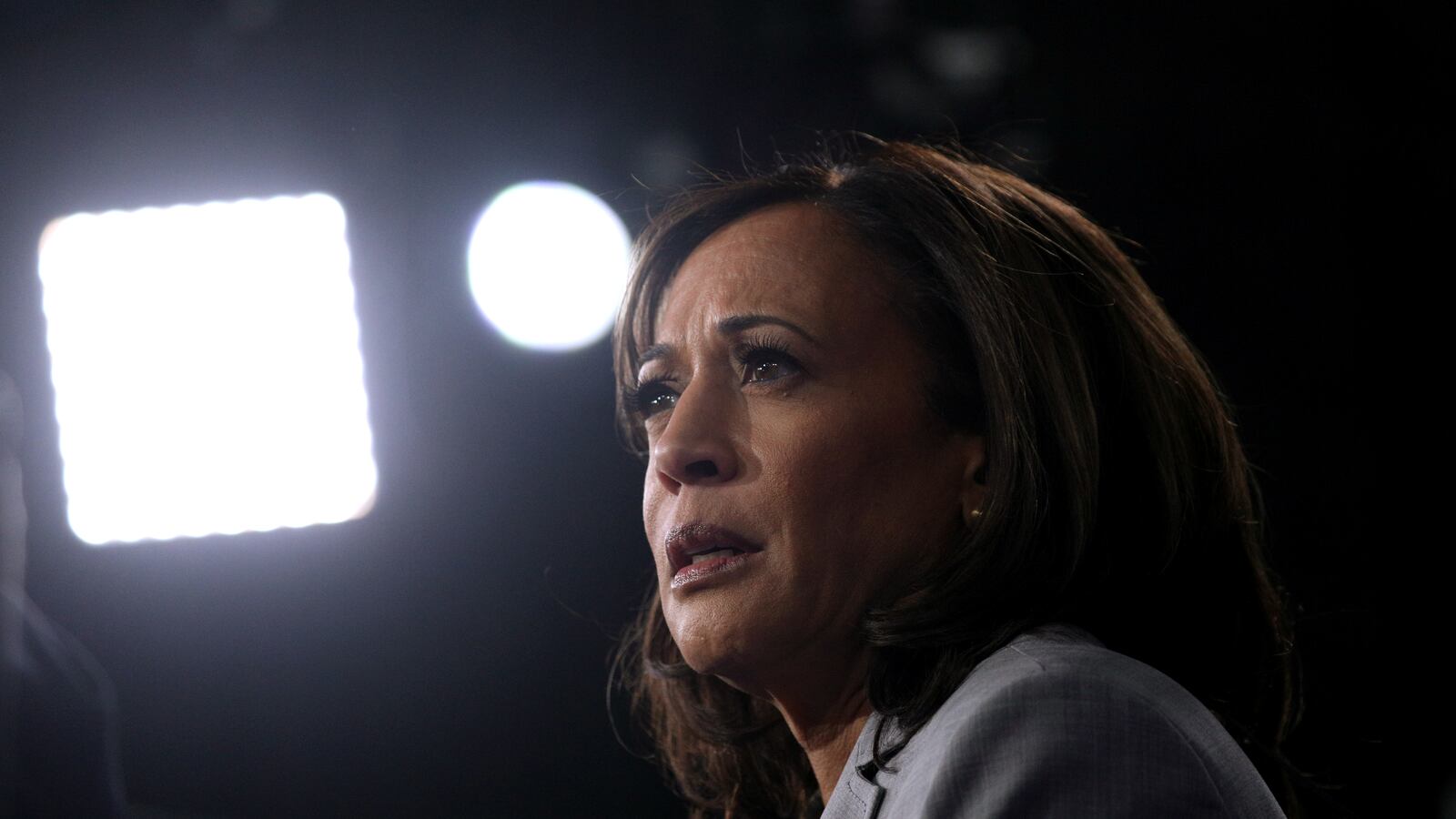

Sen. Kamala Harris (D-CA) sent shockwaves through the Democratic primary cycle on Tuesday by announcing her departure from the presidential race less than one year after officially entering it.

“To my supporters, it is with deep regret—but also with deep gratitude—that I am suspending my campaign today,” the senator said in a statement posted to Medium. “But I want to be clear with you: I will keep fighting every day for what this campaign has been about. Justice for the People. All the people.”

Although she had been faced with waning fundraising and poll numbers that had nosedived in recent months, there was a thought that she would keep pushing through the New Year in time to compete in the Iowa caucus.

But that proved to be wishful thinking.

The 55-year-old freshman senator’s splashy launch in Oakland in January, which drew more than 20,000 in attendance, turned both donors and opponents’ heads. At one point, President Donald Trump marveled at the crowd that had assembled to watch her kick off.

But Harris found herself quickly tripped up by the same policy issue that has perplexed other presidential aspirants, with some Democrats arguing her health care fumble was the start of a broader downward spiral. Just days after her announcement, she told CNN’s Jake Tapper that she supported eliminating private insurance as a part of a Medicare for All plan. Her campaign scrambled to soften the blowback. But it struggled to settle on a plan that would satisfy the liberal wing of the party and those Democrats who feared that a single-player plan would be a killer in the general election.

One source close to the campaign said that the “months-long” journey to settle on a plan sapped the campaign’s early momentum. Eventually, she introduced a proposal that transitioned gradually into a Medicare for All type system with options for supplemental private coverage. But the ten-year transition window she envisioned left some health care experts questioning whether the plan was politically viable. And in subsequent debates Harris struggled to defend her idea on the merits.

It was, said one top party operative, “a symptom that she didn’t know what she was about.”

Others saw a more problematic contributor to Harris’ fall: mainly that gender biases still manifested themselves in voter expectations and press coverage. The senator’s struggles have come as Mayor Pete Buttigieg has risen in the primary polls. And the contrasting directions of those two campaigns wasn’t lost on some.

“It's not hard to argue that Kamala and the other women have been held to different standards,” said Christina Reynolds, vice president of communications for the group Emily’s List, which works to elect female candidates. “The campaign coverage has shown too often that men just need to have potential, while women must have met it.”

But even Harris’ strongest attributes as a candidate—namely her record as California’s attorney general—were a matter of debate internally. Her record as a tough prosecutor put her at odds with a Democratic primary electorate angry about mass incarceration and the racial disparity in the judicial system. When attacked on that record in debates, she was tepid, opting to change the subject rather than explaining what had once been a signature issue.

Looking back, campaign veterans said that Harris ultimately suffered from an inability, or unwillingness, to find a theme or cause that animated her run for office.

“Her own lack of clarity resulted in a lack of clarity in the campaign,” said David Axelrod, the chief strategist on Barack Obama’s two winning presidential races. “There was a tactical theory of the case but the message never congealed… [And] the thing about shifting messages is it creates issues about authenticity, and authenticity is the coin of the realm in presidential races.”

The Harris campaign wasn’t always without promise or direction. As Axelrod noted, Harris had a prime opportunity to lay claim to frontrunner status early in the race after a stellar debate performance in which she took former Vice President Joe Biden to task for his comments and his record on the integration of busing when he was a senator in Delaware during the '70s.

“There was a little girl in California who was part of the second class to integrate her public schools, and she was bused to school every day,” Harris said in that debate. “That little girl was me.”

The line—which soon featured on campaign T-shirts and coffee mugs—vaulted her to the top tier of the race for the Democratic nomination. Soon, Harris had the second-highest number of endorsements from high-ranking Democrats of anyone in the field, trailing only Biden himself.

But that momentum did not last. After peaking in the polls at 15 percent in June, her next debate performances were uneven—especially around health care—and as a result the campaign’s struggles became more and more evident. There was no pick up in the polls even as Harris tried out different issues for emphasis; at one point making a sustained push for Twitter to kick President Donald Trump off the platform.

Operatives in the party privately mocked the impulsive nature of the operation, and donors began to question what the long-term strategy was for sustaining her candidacy. In her letter announcing that she was suspending her campaign, Harris noted that she was “not a billionaire” who could “fund my own campaign”—a not so subtle reference to the late primary entry of former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg.

“Clearly money has become an issue,” Rep. Marcia Fudge (D-OH) told The Daily Beast, stressing that in her view, Harris had hit her stride on the campaign trail in recent weeks. “It just became a situation where… this is as far as it could go financially.”

Money wasn’t the only problem, however. A shifting set of strategies also hurt the Harris campaign.

The first target was South Carolina, a state where the support of African American voters can make or break Democratic candidates. Despite making early gains in the first-in-the-South primary in July, she never managed to surpass Biden’s lead, particularly with African American voters, a loyal voting constituency in the Democratic Party.

When it became clear that voters there were not warming to her as much as other candidates, she looked west to Iowa, a place where other rivals, including Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA), Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg already had vast and deep organizations.

“I don’t think you can point to any one thing that led to this point in her campaign,” Democratic strategist Antjuan Seawright, who is based in South Carolina, told The Daily Beast. “It was very much a learning experience for all.”

Still, Harris reset much of her national operation to focus on the Hawkeye State, joking on occasion that she’s “moving” there.

But the “put Iowa first” effort—that included putting dozens of additional full-time organizers on the ground and visiting the state each week in October—flatlined, leaving Democrats on the ground skeptical that she could turn the downward spiral around in time for the Feb. 3 caucus after plummeting to low single digits.

In New Hampshire, the story was even grimmer. In recent weeks, Harris gutted nearly her entire operation there, as part of the related push to compete in Iowa and, the thinking went at the time, take that momentum to the first-in-the-nation primary. But multiple Democrats in the Granite State speculated that her campaign would have trouble catching up to rivals, including two neighboring senators, who have for months built out sizable teams dedicated to winning the primary in February.

“She is talented and it wouldn’t shock me to see her on the national ticket. We haven’t heard the last of Kamala Harris,” said Axelrod. “But this was a troubled enterprise from the beginning because there was no clarity.”

—With reporting by Scott Bixby.