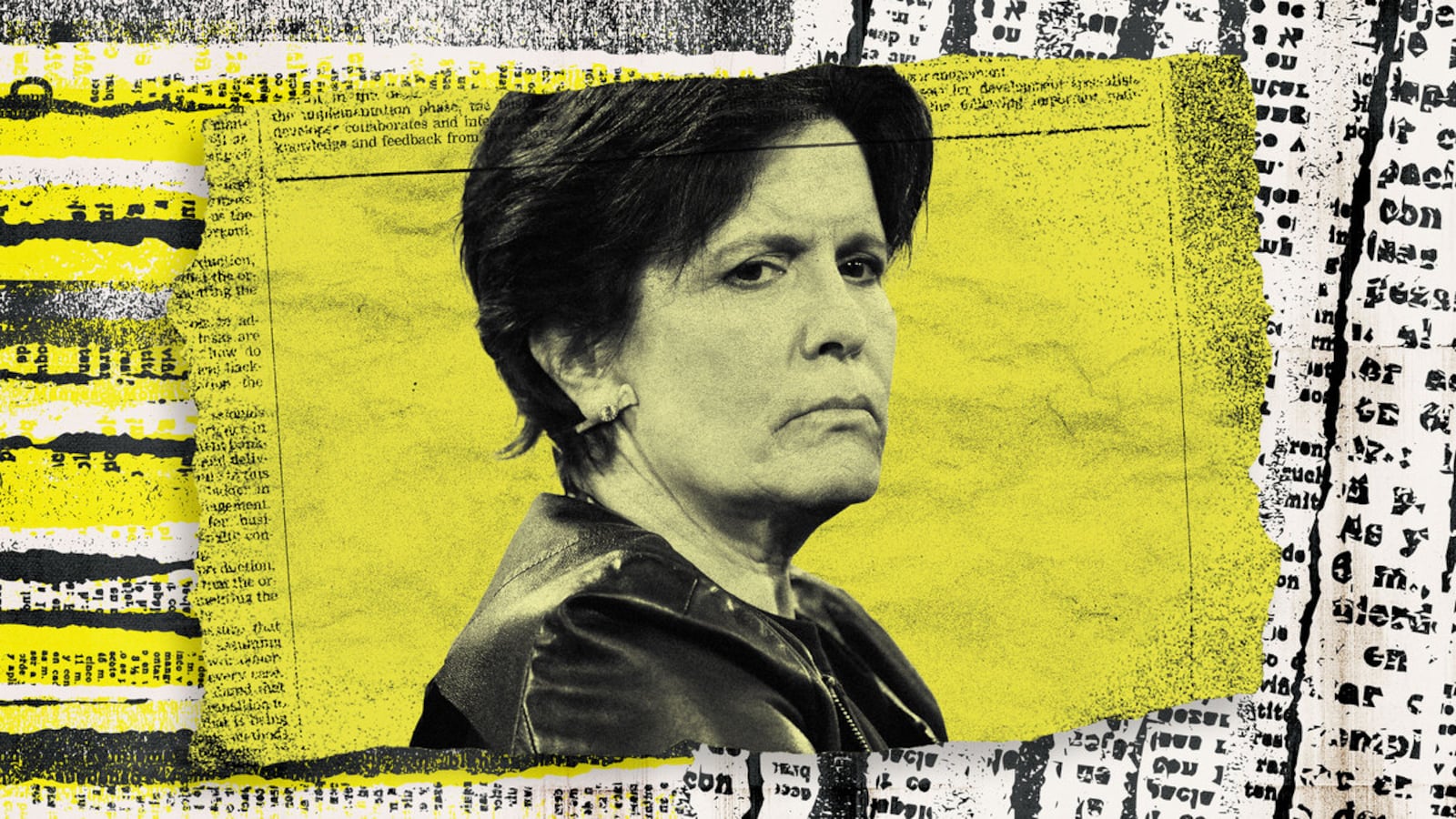

Kara Swisher describes herself in the final pages of her new memoir as “a longtime tech reporter and raconteur,” someone able to tell stories in a captivating, amusing way. It’s a necessary skill for explaining the ongoing collapse of digital media, especially following the last two months’ “extinction-level” layoffs at publications from the Los Angeles Times to the zombie-like Vice to the now-defunct The Messenger.

“I don't think they're particularly good businesses anymore,” Swisher told The Daily Beast over a Zoom interview late last week. That’s not just the fault of billionaires like Jeff Bezos and Patrick Soon-Shiong, the respective owners of The Washington Post and the L.A. Times, but the natural progression of things under tech’s rapid advance: dominance and then antiquation.

“These businesses have economic systems not in line with our costs,” Swisher said. “That's pretty much one of the things media doesn't like to do is pretend costs need to meet revenues. Normal reporters don't think about that.”

Drawing from her decades of experience at The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, and her own ventures at AllThingsD and Recode, Swisher chronicles in her memoir Burn Book: A Tech Love Story (out Tuesday) how tech supported—and helped kill—the modern media industry. A dependence on digital advertising (supplemented by Google) and social media (aided by Facebook and Twitter) for traffic and revenue helped build massive multimedia brands like Vice and BuzzFeed News—both of which cratered over the past year thanks in no small part to those same tech companies’ dramatic pivot away.

The book was necessary for Swisher to write at this juncture of her voluminous career, both “in case I die” and, as a self-described media and tech Cassandra, to warn how “what’s coming next” for digital media “is even bigger.”

More specifically, Swisher identifies artificial general intelligence, or AGI, as the next big threat. AI’s next frontier is still in its relative infancy, but its impact on this year’s presidential election already frightens her. The rise of AGI bots that can populate complete news sites risks diluting real, accurate news sources, particularly if people cannot discern the difference between them, she said.

“They’re flooding the zone of inaccurate stuff,” Swisher said. “You don’t even need players like the Russians to make a mess—they're in there too, so are the Chinese. Now these [AGI] bots just churn out so much dreck that it’s hard to sort through to the real stuff, and the platforms are doing nothing about it. It seems like they’re not elevating trusted sources of news because they refuse to choose and I didn’t ask them to choose…just put stuff we know to be news organizations.”

Swisher recounted to The Daily Beast a story she left out of the book, in which she argued with Google co-founder Larry Page at her home. Google shouldn’t list shoddier “news” sources next to established brands like The New York Times and The Washington Post, she recalled telling Page, as it would create a false equivalence.

“We had a huge argument about this,” Swisher said. “He was like, ‘Well, people can decide.’ I'm like, no, no, it’s like putting tainted meat next to good meat. People won’t figure it out quite as quickly as you think they do. You have to have some sort of way to have a wide range of opinion, but at the same time, they didn’t want to bother figuring it out, right? They didn’t want to make the choices, and it’s not that hard to make the choices.”

Swisher added: “They just didn’t want to. They wanted to just throw it all up there and ‘You guys’—like throwing library books on the floor—‘You figure it out,’ and people don’t figure it out. I was always like, ‘As smart as you are, you’re a fucking idiot.’ Like, are you kidding me? Like, you know how regular people behave?”

And while tech poses a serious threat to journalism, Swisher noted, it’s not like established media companies have helped themselves succeed longer-term. “I was there for Vice, they spent too much money,” she said. “It made no sense to me whenever I visited their headquarters and they were an advertising company, essentially, with some good journalism and some really cool shows like, Fuck, That’s Delicious. But the amount of money they spent was way out of line for the amount of money they were eventually going to bring in. So that was an issue.”

Such financial chaos hasn’t been limited to Vice. The Messenger blew through $50 million in less than a year, while media company after media company has had to shed staff at alarming rates. Jeff Bezos’ Washington Post alone lost more than 250 people last year, leaving staff fearful the paper would never reach the heights it did during the Trump administration. (Bezos, in Swisher’s view, “actually has been a pretty good owner, all things considered.”)

“Media companies rise and fall all the time,” Swisher said. “This is, again, not a fresh new thing.”

Meanwhile, platforms are also trying to figure out ways to generate more cash amid waning revenue and value, perhaps none chaotically more so than Elon Musk’s Twitter-turned-X.

Burn Book teases Swisher and Musk’s relationship throughout its roughly 300 pages, with Swisher noting Musk’s impact across various tech milestones while documenting other figureheads. (“I sprinkle him like the toxic spice he is,” she said.) But the world’s wealthiest edgelord eventually gets his own chapter toward the end, where Swisher describes how her initial curiosity about him—particularly his interest in electric vehicles and space exploration, along with his high-speed rail proposals—gave way to severe disappointment.

“These were big ideas,” Swisher said. “One of the things that had gotten me crazy as a reporter was so many small ideas from smart people, and I thought, ‘We have all these issues facing the world. Pick one: Poverty, climate change, income, inequality, blah, blah, blah. You can go on and on, right, and this is what they're focused on, making their lives in San Francisco more comfortable. So I was starting to get irritated. And he wasn't.”

But Musk’s tumble into social media’s dark abyss, taking whatever remains of X with him now, has frustrated Swisher—a descent she attributes to a combination of obscene wealth and character depravity. “He clearly is lacking in character or something,” Swisher said. “He didn't get it and or his character was so weak that he's fallen prey to, you know—what people tell him online who he has never met is more important than people who are around him.”

But people like Musk and the multitude of tech figures who frustrate Swisher aren’t why she wrote the book, nor are they indicative of where tech (and, to a degree, media) could go. The book leaves room for figures who’ve positively affected either her life, the world, or both, such as the late Zappos co-founder Tony Hsieh, former SurveyMonkey CEO Dave Goldberg, and Steve Jobs.

“I prefer to deal with adults,” Swisher said. “I would like to talk to adults, and I don’t want to talk to these children anymore because these children don't know what they're talking about.”

Still, Swisher hopes that, unlike the mythological Cassandra whose prophecies were ignored, both the “children” and adults will pay heed to her warnings.

“Because I was right before,” she said. “And some people do, some people don't. I hope that we will see what happened with the last go-round and maybe make some better choices here, going forward, especially with AGI.”