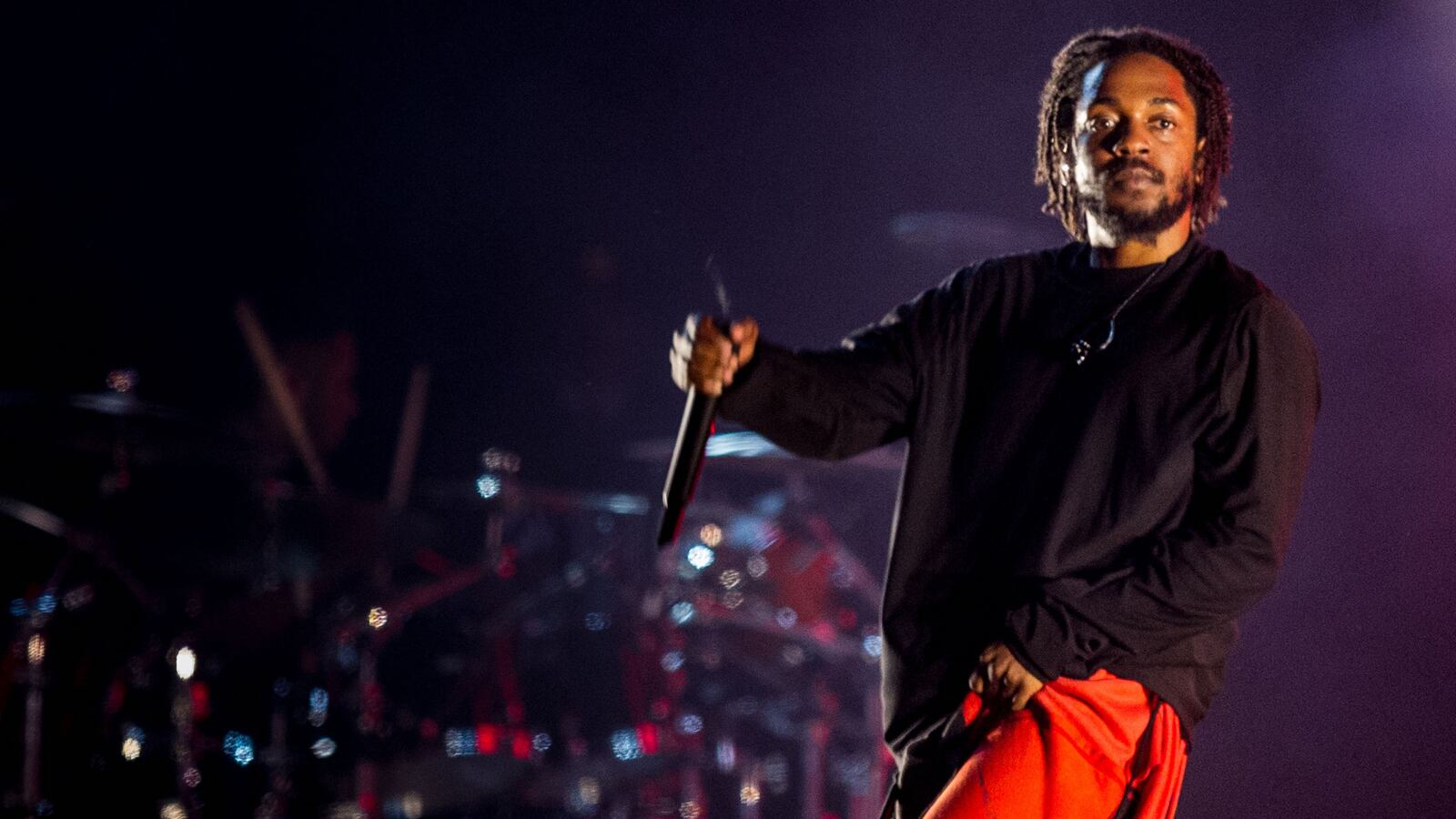

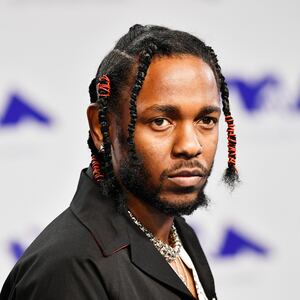

Kendrick Lamar made his grand return to music on Friday with Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers, his fifth studio album and his first since 2017’s Grammy-nominated DAMN. Other than firing off a few one-off features and spearheading 2018’s star-studded Black Panther soundtrack, Lamar has spent much of the past five years out of the spotlight; there’s been no social media content, TMZ reports, or podcast appearances. It was only yesterday, with the unveiling of the new album’s cover art, that the world even learned about the birth of his second child.

By all accounts, if you want to know what’s currently happening with Lamar, you have to wait for him to come out of hiding with his latest sermon on the mount—and if Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers is any indication, the sermoner has never been more miserable.

When Lamar released his third album, To Pimp A Butterfly, in 2015, it completely shook up the rap landscape. A politically astute, experimental, and occasionally intense fusion of what seemed like the entire history of Black music—jazz, blues, soul, funk, and West Coast rap—it handily went platinum in the U.S. But perhaps more significant to Lamar’s stature in both rap and music in general, it became capital-I Important. The late culture critic Greg Tate heralded it as “a masterpiece of fiery outrage, deep Jazz and ruthless self-critique.” Spin labeled it the “great American Hip-Hop album.” Robert Christgau called it a bid to “reinstate Hip-Hop as black America’s CNN.”

By 2017’s DAMN, it felt like Lamar had finally made the ideal record for his extremely singular perch as both a major pop star and someone people considered the new GOAT and a true artiste. An album just as conceptual and dense as TPAB, but with much more accessible singles, it became another major hit for Lamar and cemented his status as a “conscious rap superstar,” leading to him becoming the first rapper to ever win a Pulitzer.

So what exactly does Kendrick Lamar have to be so down about? It’s complicated.

Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers, an 18-track, nearly 75-minute double album (whatever that means in the streaming age), is the most anxious thing you might hear on wax in a long time, with Lamar suspicious of everyone and everything and feeling imprisoned by his own success: a recurring theme throughout his music since his first feature on a Drake album a decade ago. There’s an element of “been there, done that” with Mr. Morale, another highly experimental record about the hypocrisy of cancel culture (“N95”), the trials and tribulations of success (“Count Me Out,” “Crown”), and deciding to finally see a therapist (“United in Grief,” “Father Time”), among other things.

The most illuminating moments tend to come when Lamar delves into his role as a family man, especially on “Worldwide Steppers,” in which he calls himself “a protective father” for his daughter and his baby son, Enoch (“When I expire, my children’ll make higher valleys,” he raps). On the same track, he gives some insight into his musical hiatus and his long-awaited return: “Writer’s block for two years, nothin’ moved me / Asked God to speak through me, that’s what you hear now / The voice of yours truly.”

Mr. Morale feels like a spiritual continuance of To Pimp A Butterfly, both in subject matter and in its cluttered and high-concept nature. But Mr. Morale—despite its stacked features from Summer Walker, Thundercat, Portishead’s Beth Gibbons, Ghostface Killah, Baby Keem, and more—is much more inward-looking, with Lamar examining the personal trauma of coming from nothing and suddenly having everything, and the stress of being seen as an iconic rapper, which seems to have boxed him in more than anything else.

Playing into that is the constant, lazy labeling of him as a “conscious rapper,” which has become a blanket term for anyone who doesn’t do trap or drug rap. While you can certainly learn a great deal from Lamar, his music is much more concerned with alienation, anxiety, and the existential question of “what kind of man should I be?” Throughout all 18 tracks, those feelings pop up with an intensity and exasperation that proves interesting as an artistic statement, but struggles to support an entire body of work. The first third of the album, in particular, feels more like free-flowing ideas with some music scored underneath, rather than fully formed or idealized songs.

At the heart of Mr. Morale is the tug of war between conflict and reconciliation, as Lamar attempts to contend with his misogyny on “We Cry Together”—which uses a Florence + the Machine sample and takes the form of an argument between Lamar and a woman voiced by Zola actress Taylour Paige—and transphobia and homophobia on “Auntie Diaries,” in which he comes to terms with his auntie being transgender. But deploying Kodak Black, who has been accused of sexual assault, is much harder to reconcile with, particularly as it reeks of how Kanye West loudly championed DaBaby and Marilyn Mansion after their respective allegations of homophobia and abuse became public. Lamar, for better or worse, seems less concerned with moral goodness and more interested in how people’s surroundings shape their behavior. Even so, it’s a feature that certainly won’t go uncriticized.

But that’s part of the lonely journey of Kendrick Lamar, trying to wrestle his personal opinions, thoughts, and feelings with an unsparing world that has bottled him within its spotlight. The more he achieves, the lonelier he is, trying desperately to make sense of the acclaim that he both pines for and wants to rebel against, and sometimes floundering in those efforts. He is trying, though. At least give him that.