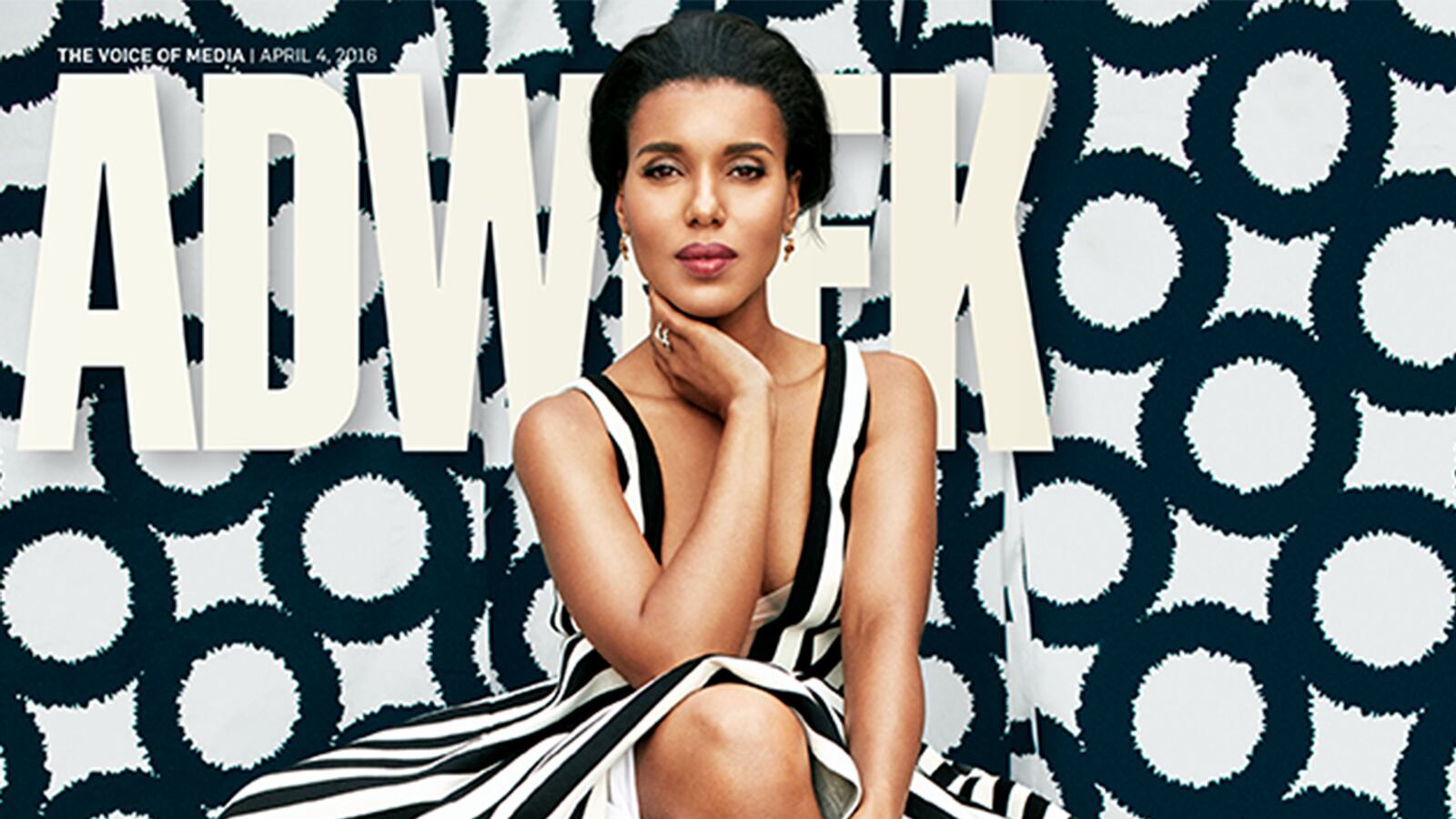

The actress Kerry Washington has been widely praised for her eloquent taking to task of Adweek magazine.

Washington claims the magazine overly-Photoshopped her for their most recent cover, but is not specific about how they did so.

Instead, she wrote an extremely polite Instagram post about her experience and feelings.

Washington wrote, “It felt strange to look at a picture of myself that is so different from what I look like when I look in the mirror. It’s an unfortunate feeling.”

But nothing is specific in her post, so it’s hard to know what she found so discombobulating. Some articles suggested her skin had been lightened, but Washington didn’t say this. Had her nose been made thinner? Had Washington been Photoshopped to make her closer to a “white” beauty standard?

There was no mention of racism in Washington’s own criticisms, just as there was no mention of what offended her about the image.

“Look, I’m no stranger to Photoshopping,” she said. “It happens a lot. In a way, we have become a society of picture adjusters—who doesn’t love a filter?!? And I don’t always take these adjustments to task but I have had the opportunity to address the impact of my altered image in the past and I think it’s a valuable conversation.”

It is, and many have praised Washington for this “honesty,” but what has she been honest about, and what is she criticizing? It isn’t clear. What is the “valuable conversation” exactly: She kind of likes to be Photoshopped, and kind of doesn’t.

For their part, AdWeek says they made her hair bigger, but that was it.

“Kerry Washington is a class act. We are honored to have her grace our pages,” said Editorial Director James Cooper. “To clarify, we made minimal adjustments, solely for the cover’s design needs. We meant no disrespect, quite the opposite. We are glad she is enthusiastic about the piece and appreciate her honest comments.”

On Twitter, Cooper said AdWeek had “added volume to hair for dramatic effect.”

Last year InStyle was forced to deny it had lightened Washington’s skin in another controversial cover.

The weird Washington contretemps comes after Lena Dunham castigated a Spanish magazine for the same “mad Photoshop” transgressions—but the magazine hadn’t done that much to doctor an image already approved by Dunham’s representatives, and Dunham apologized.

Modern makeup techniques and digital technology means our faces in print or on screen can be manipulated to look any way we, or a publication, wants. And yet, this freedom to change, this capacity to be a chameleon at the click of a button, also comes at a time when there is also a desire to appear “real.”

Any Photoshop or retouching brouhaha feeds the accompanying tributary of “body shaming,” and racism when skin has been allegedly lightened.

In what now seem very olden days, we giggled, a little awestruck and bewitched, when certain stars got the “Vaseline lens” treatment—the aging actress whose camera shots were so artfully misty they may have taken years off her, but the trickery was obvious as well as de-aging.

Today—as Logan Hill’s recent, excellent Vulture piece on the new wave of digital and visual effects employed by TV and movies, makes clear—not only can pimples be made to disappear in post-production, but also just the right amount of moisture added to a body for maximum sexy effect after a shower, as well as six-packs added to male action stars, indeed whole faces changed.

Kerry Washington and Lena Dunham may know their own faces better than anyone, but those same faces, after being polished, buffed and painted by a team of specialists, and then photographed and tweaked by tech wizards, will not look like these “real” faces—and they sign up to that when they shoot magazine covers.

How “real” a star wants themselves to look is the presently unasked question. It’s always easier to criticize a magazine than it is to interrogate the understandable contradictions of another human’s ego and vanity.

Makeup and retouching is there for a reason. If any star looks too “real” a gossip mag is always ready to leap on a zit, visible weight gain, a sign of soft flesh, a spot, an unmade-up face, a wardrobe malfunction, an accidentally visible nipple.

How to defy this hounding? Head-on, perhaps… For all those Hollywood stars who complain about how their faces and bodies look different on magazine covers, one could say: OK, just turn up to the shoots in your everyday garb, no makeup, no anything. Insist on being shot as such by the magazines, or TV or movie companies. If the level of unreality of a magazine shoot is so offensive to celebrities, they should stop being so complicit in it.

Maybe the truth of how Hollywood stars feel about Photoshop is as muddy as their anguished, imprecise musings on the subject seem to be. On the few occasions I have sat in a makeup artist’s chair before a TV appearance or photographer, the general mood of those awaiting a camera’s imminent attention is: “Do whatever you can to make me look as good as possible, because lots of people are about to see this.”

What Photoshop does is take that already softened image and refine it more.

This refinement, as the editor of AdWeek made clear, is less about offending the subject by changing them radically as it is about making the image on that magazine’s cover arresting. Colors are dialed up and down, contrasts sharpened. Designers and editors want that image to look as pin-sharp and dramatic as possible for the newsstand.

Perhaps this end result is alarming for the subjects to see. But they, their agents, their reps wanted them on that cover. Did they insist on “no Photoshopping” before they sat for the photographers? Would they or their representatives rather they looked as unmade-up and unchanged as possible?

Perhaps they should state exactly what the bounds of the photographic process are at the beginning.

When they put Vaseline on the lens in the old days, the ruse was visible. Today, the ruse is done anonymously, away from our eyes. We didn’t mind the Vaseline back then: It added glamour and mystery. Today it makes us recoil: We know too much. Today, we are suspicious of all the techno-trickery, yet also in thrall to it.

We non-celebrities are able to retouch and recalibrate our own images, play with filters and contrasts. We’re our own brands, marketing our faces to the world through Twitter, Instagram, and the rest.

The ideal look now, as professed by Kerry Washington, is to look real but polished: glamour without the visible effort needed to achieve it. The irony is, it takes a lot of people—skilled “glam squad,” skilled photographer, and skilled retouchers—to make celebrities look that slightly tweaked notion of “real.”

The “real” we see on TV and in magazines—no matter how fresh and unfussy it seems on the page or screen—is as artfully confected as Joan Collins’s vivid maquillage on Dynasty.

Maybe Hollywood stars themselves need to get real, and accept the magic of the retoucher’s wand—unless, and good luck to them, they want to dismantle the absurd aesthetic hegemony so present in their professional lives, which they are complicit in.