Influential Kenyan citizens and expatriates have told The Daily Beast they want King Charles to use his forthcoming visit to the country to make a full and frank apology for crimes perpetrated by British overlords as they crushed the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya between 1952 and 1960, one of the bloodiest episodes in colonial history.

One man, a Kenyan-born British lawyer and councilor, whose elderly grandfather was killed by British troops in 1956 while he was harvesting honey, described it as “very offensive” for Charles to contemplate traveling to the country without offering an apology and opening a discussion on reparations.

So far, the Palace has refused to be drawn in detail on the question of how the king will deal with the divisive and toxic legacy of British colonialism in Kenya, with advisers only saying that he would acknowledge “painful aspects” of the countries’ “shared history.”

“Shared history” may seem to some a rather inadequate way of describing the events of 1952 to 1960, which saw a state of emergency declared in the country after a million-strong army of indigenous Kenyans, who called themselves the Mau Mau, rose up with the goal of taking back land seized by the British and expelling their colonial masters.

The British response was savage: tens of thousands of supporters, many of whom had themselves been violently forced to declare allegiance to the Mau Mau, were herded into concentration camps, where they were subjected to beatings, rape, castration and summary executions. The Kenya Human Rights Commission found that 90,000 Kenyans were executed, tortured or maimed. Official figures show that 1,090 people were hanged and say another 10,000 died, but academics such as David Anderson, professor of African Politics at Oxford University, estimated to the BBC that the death toll in the conflict was 25,000.

By contrast, just 32 white settlers were killed over the eight years the state of emergency was in place.

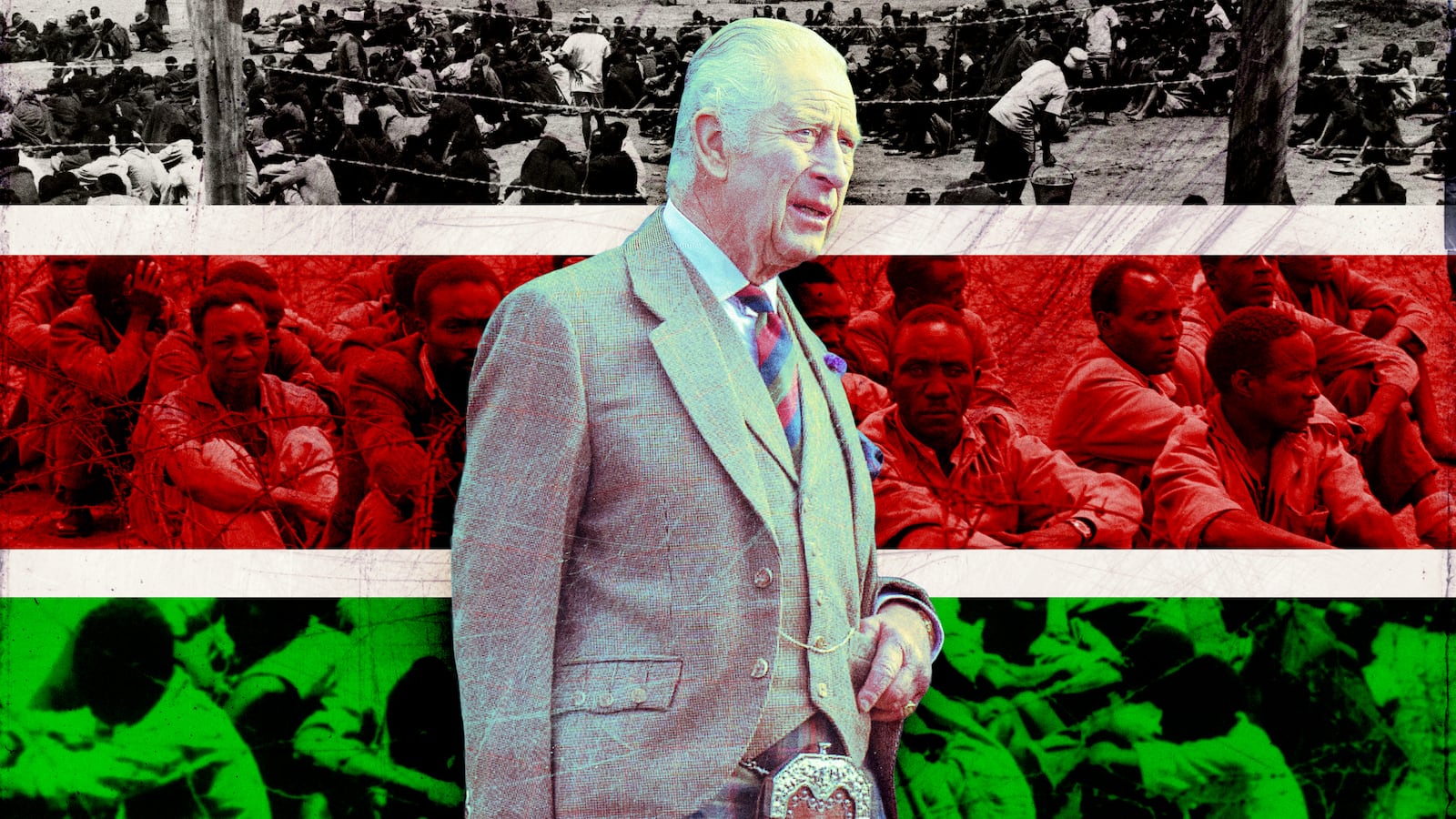

British policemen hold men from the village of Kariobangi at gunpoint while their huts are searched for evidence that they participated in the Mau Mau Rebellion of 1952.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesThe British government in 2013 admitted wrongdoing and said it would pay out £19.9m ($24.1m) in costs and compensation to more than 5,000 elderly Kenyans who suffered torture and abuse during the Mau Mau uprising in the 1950s and admitted that “Kenyans were subjected to torture and other forms of ill-treatment at the hands of the colonial administration.”

However, a further 40,000 Kenyans who then sued the U.K. government for compensation were not compensated, and lost their case in 2019. According to a report in the Guardian, the judge “concluded that the passage of time since the alleged ill-treatment was so great that it was impossible for the crown to mount a meaningful defense, especially in the absence of virtually any corroborative evidence,” as “nearly all those alleged to have committed the claimed offenses were either dead or not traceable.”

It is unsurprising, therefore, that the issue is a hugely emotive one, with many arguing that vague and generalized expressions of regret will not suffice.

Take, for example, Dominic Kirui, a Kenyan athlete and double Olympian turned writer. In a telephone interview, he told The Daily Beast: “A royal visit in itself is not something that many Kenyans would have wanted or needed, because it awakens thoughts and feelings about the colonial past that many people have buried and never want exhumed.”

Kirui comes from a region in the Rif Valley where, he says, “the scars of colonialism can still be felt and seen. The people in Kericho were driven out of their homes and their ancestral lands and forcibly resettled in Nyanza, on lands that were infested with the tsetse fly, which it was hoped would kill them. A royal visit only serves to remind people about the injustices that were committed and the pain they suffered, so I cannot believe it is something Kenyans would be eager to see or witness.”

Kirui points out that stories of oppression are common “all over Kenya” especially where huge tea farms comprising thousands of acres were carved out.

Kikuyu tribe members held in an internment camp by the British government during the Mau Mau Rebellion.

Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis via Getty Images“The people whose land was stolen... still live among the farms,” Kirui said, adding, “I see the visit by the royals as a way of the colonists saying to Kenyans, ‘We are still around. You are not as sovereign as you think you are.’”

Kirui dismissed the generalized expressions of contrition made by Charles’ office saying that what was needed was “reparations to ensure people are compensated.”

A spokesperson for Buckingham Palace asked about the prospect of an apology said that as the king is traveling to Kenya “at the request of the British Government” questions about an apology “would be a matter for them.” They directed the Daily Beast towards the text of the 2013 apology. (The Foreign Office did not respond to a request for comment.)

An official source in the king’s office added: “The visit will acknowledge the more painful aspects of the U .K. and Kenya’s shared history. His Majesty is fully aware of the context and will take time during his visit to hear from Kenyans who experienced, or whose loved ones experienced, the wrongs of this period first hand, to deepen his understanding. As well as acknowledging the wrongs of the past, the visit will look to the future, celebrating the strong and dynamic partnership which exists between Kenya and the U.K.”

British troops during the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya.

Bettmann/Getty ImagesJames Mugo, a Kenyan-born lawyer who has lived in the U.K. for 26 years, has a very personal sense of outrage about what the British did in Kenya. In the mid-1950s, his grandfather, who was in his late seventies, was shot and killed at point-blank range by British soldiers as he emerged from a forest where he had been gathering honey from beehives he kept there. He was far too old to be mistaken for a Mau Mau fighter.

Mugo told The Daily Beast: “Unless King Charles delivers anything less than an outright apology for the crimes committed by the colonists, he will not be welcome in Kenya. There are millions of people who are still languishing in poverty right now as a result of the British’s actions. They lost their land and were put in concentration camps and villages and exploited for cheap labor. I don’t see why Kenyans cannot be compensated.”

Speaking about his grandfather’s murder by British troops, he said: “He was not fighting. He was 70 years old and he was shot by British soldiers collecting honey. So I personally find it very offensive that King Charles can go there and not apologize for what happened. Very offensive. It is adding insult to injury.”

Kenya is an enormous country, about the size of Texas, with 53 million inhabitants, which has been riven with political division since long before independence. It is not entirely surprising, therefore, that many Kenyans take a different view of the forthcoming visit of the king.

Robert Kibet, a freelance Kenyan journalist who writes about the region for numerous Western outlets, told The Daily Beast: “There are strong historical ties between the countries, and these kinds of trips offer significant opportunities for cultural exchange and building bilateral diplomatic relations, but of course it all depends on the focus of the itinerary.

“Economic partnership is key for us, trade relationships which will attract investment and give business opportunities to Kenyans. Russia wants to be in Africa, China wants to be here, and so it is not surprising the U.K. wants to be here too.”

Kibet says the issue of the environment and the climate crisis is likely to be an important area of common ground because Kenya is a regional leader on the issue, having recently hosted the African climate summit, and Charles is well-known for his interest in the subject.

One white British charity executive who previously worked in the voluntary sector in Kenya told The Daily Beast: “The colonial legacy isn’t as much of an issue in daily political discourse as you might expect just because the country has faced and continues to face so many other political and economic challenges, as well as security issues and natural disasters. These are what actually preoccupy people day to day in my experience.”

Dr. Samson Ruben Ndegwa, 75, a community leader living in Nairobi, who saw his father imprisoned by the British in a concentration camp during the Mau Mau uprising, told The Daily Beast: “The British rule in Kenya has got two sides to it. They brought education to this country, for example. On the flip side of it, there was the oppression, the forced labor and the colonization which particularly affected people from the Central Province. They rebelled, they went to live in the forest, they fought.

“My father was one of them, but he didn’t die, he survived. He came out, he started a business and he educated us. He moved on. Of course there was some bitterness but many people, after independence, like him, just decided to move on.”

Asked if he supported the visit, Ndegwa said: “Let him come, by all means.”

On what Charles could or should say, Ndegwa said, “If Charles was bold enough to apologize on behalf of the British government, I think that would solidify the relationship between Kenya and Britain. The President said, ‘You forgive, but you don’t forget,’ and I think that is probably how a lot of Kenyans feel about the king’s visit.”