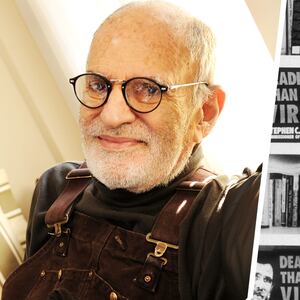

Larry Kramer, the late LGBTQ and AIDS activist, author and playwright, has been much praised and analyzed over the last 24 hours. But Larry Kramer was also both a friend and professional collaborator to many. Lost amid the tales of fire and brimstone are stories of a certain paisley pocket, an unexpected delivery of chicken soup, and the linking of arms late at night on a Broadway street.

In my obituary of Kramer, who died Wednesday at the age of 84, I mulled what people invariably mention most about Kramer: his anger. That anger, as I wrote, could be both telling and deceptive. Kramer, both artist and activist, was dedicated to a better world for LGBTQ people and people with AIDS. He was uncompromising in his activism and writing to achieve that.

He fought, bare-knuckled, for both. But around his friends and loved ones, Kramer was kind, thoughtful, and gentle. His plays—like him—could be as quiet as they were loud, as sensitive as they were bombastic.

The thread running between his words on the page and his activism Kramer’s knowledge that the fight for equality and justice was never-ending; he also knew that, at moments like this, living under an administration eager to do anything to harm LGBTQ equality and rights, people needed to stand up. Those who knew him saw that passion up close—working on his landmark play The Normal Heart or alongside him at ACT UP—and so much more.

Below, in emotional interviews, actors, activists, and friends—including Ellen Barkin, Joel Grey, Anthony Rapp, Matt Bomer, and Daryl Roth—share their memories of Larry Kramer. Tim Teeman

Ellen Barkin (The Normal Heart, 2011)

I have many important memories of Larry. For the 16 weeks The Normal Heart ran on Broadway (in 2011, for which Barkin won a Tony Award for her role as Emma Brookner, a physician), Larry never missed a performance.

He would come to about three shows a week, and would climb the four steep staircases of the Golden Theatre to kiss every actor and thank us for our performances. And he was outside the theater every night, handing out fliers, especially to the young kids who came to see the play.

The wheelchair Emma used had a little compartment for books and papers. The one we were using was falling apart. One day the stage manager said, “We’re going to change out the broken pocket thing.” And they did, and I did the performance that night, after which Larry burst into my dressing room and demanded, “Who changed that pocket?”

I said, “It was worn, there were holes in it.”

“That doesn’t matter,” Larry said. “This one has flowers on it. Do you think Emma would have a pocket on her wheelchair with flowers? Get the paisley back right now!”

And the paisley came right back.

He would say, “See, if I wasn’t here tonight that flowered thing would have gone on stage, and ruined your whole character, Ellen.”

We became friends. He had a great sense of humor, he loved to joke. He had a great love for young people. Larry Kramer had the spirit of a kid as an 80-year-old.

Larry Kramer and Ellen Barkin attend The Normal Heart after-party for the 2011 Tony Awards at the Amsterdam Ale House on June 12, 2011, in New York City.

Bruce Glikas/GettyWe only had 10 days of rehearsal. What got us through was that Larry’s passion seeped into us. I became Larry. I think we all became Larry. We didn’t just become our characters. We became manifestations of Larry. There’s Larry in every one of those characters.

Imagine someone running up and down those stairs three times a week, screaming, tossing out leaflets. You know how many kids come up to me and say, “I stood at that theater and waited for Larry Kramer to sign my program, and he gave me a leaflet and I still have it.”

For months we lived inside the power of Larry Kramer. He gave us his love and his righteous rage. For that I am forever grateful.

I met Larry for the first time on the Charlie Rose show in the late 1980s, or early 1990s. I was a young actor, and it was a big deal. It meant you were being taken seriously. I was waiting to go on, when I see, “Who’s being fucking interviewed? It’s Larry fucking Kramer.” I’m like, “Oh, this is great, this is the act I have to follow.” I have been in New York since I was born. I knew exactly who Larry Kramer was. I knew I didn’t stand a chance.

When he walked out I just shook his hand. “I’m honored to meet you, Mr. Kramer,” I said. That was my first hello. He didn’t know who I was, of course, but he was friendly. I was just flattened, I didn’t want to go out there. What the fuck am I going to talk about? Look at what he’s talking about. Changing the world. And I’m going to talk about a movie? Really?

Larry Kramer is a hero. He changed my life in not only ways I couldn’t imagine, he also changed a very hard belief of mine. I’m a cynic. I do not believe that one person can change the world, but Larry Kramer changed me. Without Larry Kramer I couldn’t have opened my mouth in 2018 (when Barkin alluded on Twitter to an incident involving Terry Gilliam in an elevator).

I couldn’t have helped any of my girlfriends if it wasn’t for Larry Kramer. Larry Kramer taught me to open my mouth and not close it until you saw change. He taught me to lie down and don’t move until they see you.

The fact this man lived through what he called “three plagues” in The New York Times is devastating to me. He was one of our most valuable activists. He always will be.

We also did a reading of (Kramer’s 1992 play about his family) The Destiny of Me and had such a wonderful time. It had meant so much to us to have done The Normal Heart on Broadway, and I know it meant an enormous amount to Larry. The idea that a little nothing like me could bring something to Larry fucking Kramer: oh my god, thank you.

I took offense to The New York Times’ suggestion that his anger sometimes outshone the good work he did. I don’t believe it. I think that without Larry’s anger nothing would have changed.

It reminds me of the African filmmaker Ousmane Sembène once being asked if rage got in the way of his art. Sembène took a big pause, and said very calmly, “My rage is my freedom, my rage is my art.”And that is Larry Kramer. He could write his rage, just like Sembène put it on film.

Larry Kramer is a fucking 20th-century American hero, who taught everyone who came into contact with him how to do the right thing, and to do the right thing. Whether you listened or not was up to you, but I know everyone on our stage listened to every fucking word that every other actor was saying because in those words was a map as to how to live your life in a way that was reaching out to help others.

I loved the story, which he liked to tell, of being in the elevator with his dog and (former New York mayor) Ed Koch, and telling his dog that this was the man “killing all of daddy’s friends.” Larry and I both had Wheaten terriers. Larry said he loved it even more when the elevator was crowded. And that was probably one of the nicer things he said about Ed Koch.

I wish I believed in heaven and hell right now. If the scene in that elevator was bad, imagine them both now. Well, no, Ed Koch would not be where Larry Kramer was, and should they be together I think Larry Kramer would get all the good people, and Ed Koch would have to go down below where he belongs.

There was no one like Larry. I grew up in the 1960s, yes, but I didn’t spend my young adult life around serious activists. I wasn’t a big believer that the world changed that way. Larry just flipped that switch for me, and every time I open my mouth I feel guilty that I can’t be as courageous as Larry could be.

But that courage is in me, it’s in all of us. That is what Larry Kramer taught me. We have the courage in us to fight, we all have the energy, we all have the strength. And now, right now, it’s happening again. Where is our Larry Kramer? There was only one Larry Kramer, just like there was only one Malcolm X. He was a giant. And there is no Larry Kramer now. I’m just confused and sad.

I think he liked me very much. I never saw Larry be anything but loving, but I did see him rage about something that deserved it. He was so gentle with the actors. You might think there would be a possibility of someone like that throwing their weight around. There was none of that. Larry lived just as what he fought for: every human being deserves respect.

When it comes to his legacy, Larry was a humble guy but not so humble he didn’t understand the impact his life has had. Larry Kramer was a grown adult who dedicated his life to something. He was not bothered by trivialities and smallness. He knew who he was and what he has done, and what he has done is massive.

I don’t have much respect for hide-behind-the-door types, and that’s not Larry. And if you were intimidated by him, then too bad for you because he’s not in the least intimidating. I once met him with a friend of mine, who he didn’t know and who wasn’t famous, and Larry just chatted to them. There was no who’s-coming-first, and order. It was all his art and his cause.

He got very angry when he spoke about Trump. He felt about Trump the way everyone else does, but more so because this was Larry Kramer. He was what you think he would be: a very passionate guy. And I kind of learned over time there was literally no stopping Larry Kramer. You couldn’t stop him. His belief in outing closeted gay men was, to me, his greatest action because it was honest and true, and they’re lying. If they came out back then, they could have helped get money for HIV and AIDS medications.

At the beginning of the #MeToo movement, I felt strongly that what I should do was call out the names of everyone I knew who was bad, but maybe I didn’t have the proof and honestly I am not as courageous as Larry Kramer. He certainly inspired me to be more so. I kept those opinions to myself, selfishly I realize. If you get one person to open their minds and eyes, you shouldn’t keep your opinion to yourself.

You know what else I think? I think Larry had that effect on all of us. I look at Mark Ruffalo (who starred in the movie adaptation of The Normal Heart) and I say, “I see Larry there, I see you.” I always see Larry in Joe Mantello. Always. That sense of commitment, that sense of “I’ll fight for it until I’m lying on the ground.”

It was so inspiring being on that stage in that room. That inspiration started at the top. It always starts with the word, and the words were his. Larry guided us with love, compassion, and his relentless spirit.

I think for Larry, love was a huge force in his life. Larry loved his friends unashamedly. Larry loved me. When I ran into him on the street I knew he loved me. I once ran into him at Shakespeare & Co. (the bookstore), and thinking, “Oh, this is Larry Kramer, loving me, kissing me. Hello. Wow. Larry. Kramer.” That’s a big deal for a little New York girl like me who remembers ACT UP, and who lived across the street from the LGBT Center on 13th Street.

Oh god, I’m going to go back to crying. If I talk any more, you’re just going to have bad quotes.

Joel Grey (The Normal Heart, 1985)

Larry had been struggling for quite a while. I’m smiling because now I think he’s out of danger. He was such a force, and full of a kind of excitement and fierceness about what he believed in that was so prophetic at the time.

I first saw The Normal Heart in previews. I was so moved and impressed with the nature of it—as something happening right in that moment. I said to Larry, “I want to be part of this. Please call me if anything happens.”

It was an honor to play Ned Weeks (in the original 1985 production). Brad Davis got sick during rehearsals and (producer) Joe Papp called me and said Brad was going to have to leave. (Davis was diagnosed as HIV positive in 1985, and died in 1991.) Joe asked if I would I get into the play as quickly as I could, which I did.

There was a doctor at UCLA back then—I think who was looking after Rock Hudson—who I was told to call. This was a time when everyone was afraid of everything. It was thought to be dangerous to sit at the same table or drink from the same glass of water as someone with HIV. I asked the doctor if it was dangerous for me to kiss, passionately, another character. He said not to do it. I decided I had to. I knew the play had to go on, and the story had to be told.

Larry was a hard taskmaster and opinionated, and so supportive of what I did. It was one of most gratifying and terrifying experiences of my life. All of the people in the play were real, they were all there at the beginning of Gay Men’s Health Crisis. Later, I directed the 25th anniversary benefit reading of the play, starring Joe Mantello. Larry’s experience of human life made him need to tell that story. Somewhere, Larry had to know he was finally heard.

Joel Grey and Larry Kramer attend the 2011 New York Drama Critic’s Circle Awards at Angus McIndoe on May 16, 2011, in New York City.

Bruce Glikas/GettyI talked to Larry often. He was working on a new book, working all day long, and totally into new work and new ideas—and fighting to the end. Of course, he had a lot to say about Mr. Trump, as do we all.

There was another side to him. He was jolly and sweet and full of stories, and yes, opinions. That’s what made The Normal Heart what it was. It did not shrink from the subject.

Sean Strub, author, activist, mayor of Milford, PA

The news of Larry’s death hit me like a gut punch, and oddly I was in the middle of a phone call discussing this present pandemic and testing (with local officials in Pennsylvania) when I heard the news.

I first met Larry at a Lambda Legal party in the early 1980s. I became aware of him when he first started speaking out. I didn’t really get to know him until ACT UP started.

In the summer of 1987, I had broken my leg on July 4th. I was working on a fundraising letter for ACT UP.

Larry came over to my apartment a couple of times with his dog, and I remember he brought me chicken soup, which I teased him for. I said, “Isn’t that for a cold? I broke my leg.”

That was the gentle, caring Larry. There was such a dichotomy between the public image of the bellicose, obnoxious, sometimes abusive, loud, passionate activist, calling people “Murderers” and all that kind of rhetoric, and the very loving, gentle, thoughtful, loyal friend who was always worried. He would always ask, “Do you have a boyfriend?” “Is your relationship going OK?” “It looks like you lost a pound or two. Are you eating OK?”

A lot of that parental love is in him; my heart goes out to (Kramer’s surviving husband) David Webster. He was immensely happy with David. I don’t think there is any question that the last 20 years of his life were the happiest he ever had.

My heart also goes out to the thousands who are in various ways his children, and he would refer to some of us in ACT UP as his “children.” He would also grandly refer to “my people.”

Larry could be “on stage” at a dinner party, or in front of hundreds of people. “Off stage” I found it easy to challenge what he said and the style in which he said it. A lot of his explosive public pronouncements were quite calculated. When I disagreed with him, he was always curious why. We had great back-and-forth discussions. I found I wrote more powerfully when I was angry. We connected on that. Too much thought, and we both felt you would water down your words and not be as effective.

In terms of the activism of ACT UP, the dynamite was there. Larry knew how to place and light the fuse. Would we have had a different epidemic if it hadn’t been for Larry Kramer? Yes.

Larry Kramer at a Village Voice AIDS conference on June 6, 1987, in New York City.

Catherine McGann/GettyHe saw himself as the leader of a movement and a generation of people, who largely responded in kind even as his voice became dated in certain ways.

Larry hasn’t been hugely relevant in AIDS activism in recent years, because the advocacy around the epidemic is different now. It is broader, more intersectional. But Larry deserves a lot of credit for mobilizing and raising consciousness and bringing to activism a generation of gay, mainly white men, many of whom might not have gotten into activism or social justice work. Many did not stay with it once AIDS treatments were developed, but many were also inspired and grew and found their lives in this work.

Larry had a connection to New York’s intellectual and cultural elite. He was a filmmaker, then he wrote (the novel) Faggots. I think for a while he fought against being seen as a “gay writer,” then he went all in, and found that was a niche. He helped to create new ground there.

I produced David Drake’s semi-autobiographical play, The Night Larry Kramer Kissed Me. There was concern about the title. Larry was irascible, Would he sue us? I took Larry to a workshop performance of it, where he watched it with tears in his eyes. At the end he said, “Well I’m not going to give you permission to use my name.” I was a little taken aback. Then he added. “But I’m not going to sue you either.” He winked at me. I think he felt honored by it.

Larry’s passion was always on. He became gentler and more forgiving and reflective in his later years. He saw his own life in a bigger historical context, and was very conscious of his legacy.

Larry’s consistent theme was that any gains made were fragile, and there were powerful forces out to destroy us and reverse those gains. Now, under Trump, we are sadly seeing the fragility of the gains we made; we are seeing LGBTQ progress reversed all over the world. Sadly, this not the one way “up” trajectory of progress. Larry would want people to get out of their moment, and look beyond the rainbow this-and-that, and to look at the larger arc of history and the dangers we face and how much we are hated and despised.

Larry’s role in uncovering our history, even if he didn’t do it as an academic and scholar, could be as aggressive and over the top as his activism—questioning the sexuality of Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, and Alexander Hamilton, for example—but I hope it at least sparks the interest of, and inspires, younger historians in the field.

Matt Bomer (The Normal Heart, 2014 movie)

Larry Kramer was truly one of a kind. Growing up in a conservative environment, Larry was everything I was told I couldn’t be: outspoken, bold, acerbic, passionate. He was a firebrand with an incredible intellect, and a wit to match. He embodied the motto: Silence = Death. His courage informed and inspired millions, and will continue to do so for generations to come.

Larry Kramer and Matt Bomer attend the Boys in the Band 50th anniversary celebration at The Second Floor NYC on May 30, 2018, in New York City.

Nicholas Hunt/GettyWithout him, I wouldn’t have known anything about the front lines of the epidemic our community was facing. He was an artist whose work saved lives. You can’t ask for a more profound and lasting impact than that. We mourn him, we miss him, and it’s our job now to make sure his work continues.

Michelangelo Signorile, activist, author, host of The Michelangelo Signorile Show on Sirius XM Progress

I met Larry in 1988. To me, he seemed angry, irascible, loud, challenging, intimidating, inspirational, profound, motivating, a visionary. I really looked up to him. He saw his art and activism working together. Everything for him was about using different media to create a spark, get a reaction, shake things up, challenge people. He was very outspoken, and angry, about complacency. He would do anything to wake people up.

In the early years, he could not understand why a tiny fraction of LGBTQ people were not out demonstrating. He was never satisfied. There was always something more we should be fighting for.

We worked together at (former LGBTQ publication) Outweek. He challenged and championed my work on outing famous people. Sometimes he would be enormously angry, which you would have to parse to get through to the golden kernel of what he was saying that was right-on.

In recent years his health had deteriorated, but not his demeanor. His basic stands, his basic principles, remained solid. He celebrated the progress that was symbolized by marriage equality. His legacy is to never settle for crumbs, and to think of LGBTQ people as needing to be completely equal and deserving of their civil rights—not having a place carved out for them, and not being satisfied with tokens.

There is a direct through-line from the AIDS activism he did to the activism that followed in the rest of the LGBTQ movement. Larry had lived through that moment, when in the early 1980s, we thought we were making progress. Then AIDS happened, and Larry’s activism with ACT UP inspired what came next. He found it tremendously enraging not to see us all fighting the AIDS epidemic.

Now, Donald Trump is taking everything away from us again, and Larry would want people to be enraged, fighting back, standing up, and cutting through the lies of the Trump administration. He would like us to be out there.

Daryl Roth, producer, The Normal Heart (Broadway, 2011)

It’s amazing this man lived as long as he did, with the challenges to his health. I think he willed himself to stay here until he just couldn’t any more.

I met Larry at a 25th anniversary benefit reading of The Normal Heart. Everyone was in tears. I said to Larry that we ought to revive the play, which now seemed prescient and important for a younger generation to understand whose shoulders they stood on. He said, “OK, you’re a brave girl!” And I said it would be my honor, and for all the years since it really was an honor because of the difference it made for so many people.

I have produced a lot of challenging work in my day. But this play did all I hope theater can do: It activated people, it educated people, it encouraged people to go out into the world and do something. And he was amazing. He would stand in front of the theater in his orange windbreaker, handing out fliers and talking to people about what they could do to help.

I got so many letters from mostly young gay men saying the play had given them strength to either come out to their families or come out to themselves, or be proud and feel strength and supported. I’d get these letters and cry. The people in the office would be like, “Oh no, she’s got another letter.” It was breathtaking. Theater can change people, and that was one of the most powerful examples.

The night New York State’s marriage equality law passed (in 2011) the stage manager announced it to the audience. I had been working with the governor and state officials to pass the law. My son Jordan (Roth, the president and majority owner of Jujamcyn Theaters in New York City) is gay, and the issue was very dear to my heart no matter what. The audience stood up and started clapping and cheering.

The play made people emotional. People were out and out bawling their eyes out without any shame. Often in theater people snuff out their emotions or are embarrassed or whatever. This was a love-fest where everybody’s just free and the emotions poured out. It was gorgeous.

People will tell you how difficult and cranky Larry was. I never felt anything but love and respect from him. He was grateful we wanted to bring the play back. I remember seeing the original, and it meant so much to me because of Jordan. But it started everything for me.

The most important thing for me was that Larry liked the production. I really wanted to make him proud. I felt a huge responsibility. He always encouraged me. He said I was doing a great job. “Look at the people,” he would say. To me he was very kind and gentle, and we would walk down the street after the show, late at night, arm in arm.

Anthony Rapp (The Destiny of Me, 1992)

What I remember is the force of Larry’s personality and energy. He was very encouraging and supportive. I was a young actor, coming out in my life. We spent the afternoon at his apartment, where he shared stories with me. Being in the presence of someone who always argued for doing whatever you could do to shake things up and make a difference made an indelible impression on me.

We first met at a reading of The Destiny of Me. I wasn’t cast in the production. John Cameron Mitchell was, but when he left the show, I was cast as his replacement.

Meeting Larry, the March on Washington in 1993, and the displaying of the NAMES Project Memorial Quilt were a series of events that galvanized me. I came out publicly when I appeared in The Destiny of Me, off-Broadway. It was small-scale. It was just a bio in a Playbill for an off-Broadway play, but I took that step very consciously.

Larry was not shy about showing anger towards institutions, but he was also incredibly passionate about theater. The Normal Heart was personal, but The Destiny of Me was even more personal in many ways because it was about his family. His desire to be seen as an artist was as important, if not more important, to him that being known as an activist.

His legacy is amazing. He didn’t just lead an institutional response with GHMC. Then he helped set up an activist response with ACT UP. Then Faggots, The Normal Heart, and The Destiny of Me were artistic responses. He funneled himself in all these avenues.

Larry was a sensitive soul. He cared if he pissed people off, but it didn’t stop him pissing people off. He was a living example of not staying silent in the face of crises, including the ones we have today. His example is that you should do whatever you can to shake the earth. For Larry, if that meant making enemies it meant making enemies. He wasn’t careful, and he changed the world.

William J. Mann, author and historian

I spent time with Larry and David (Webster, his husband) in Provincetown, and in 2016, I got him to come speak to a class I teach on the history of AIDS.

As it turned out, he came just two days after the presidential election, when the students were shocked and devastated. I wish we’d recorded it, but his words were very inspiring. When he saw the stricken (mostly LGBTQ) students, he said, and I’ll never forget it, “I am sorry we didn’t give you the better world we thought was coming.”

There was discussion at an open forum afterward, where I interviewed him about how to be an activist. Larry said, “I’m too old. I’ll have your backs, but it’s up to all you young people now.”

Larry Kramer addresses William J. Mann’s students, November 2016.

Courtesy William J. Mann

Larry Kramer, center in scarf, with William J. Mann, wearing tie, next to him and veteran activists, November 2016.

Courtesy William J. Mann