As the novelist hired to continue Robert B. Parker’s Spenser series, I was particularly interested in what Malcolm Jones had to say about similar plans by the Raymond Chandler estate. Let me say Malcolm is a friend and a terrific critic. And although I share his skepticism of moody Irish writer John Banville (writing as Benjamin Black) taking on Philip Marlowe, I took exception with many of his points.

Jones writes bitterly about “literary tomb-robbing” and “zombie characters,” and says with absolute certainty that no good can ever come of it. While I agree this may be true for authorized sequels to Gone with the Wind or The Godfather, I think a series hero simply does not fit into that mold. A series hero’s story is never finished. And while the creator may pass away, the hero lives on in the consciousness of fans and readers. The series character was created by the author to endure.

When Robert B. Parker died in 2010, there was no neat and tidy end to Spenser, the tough and funny private eye he’d been writing about since 1973. His loyal fans expected another adventure, a new client strolling into his office at Berkeley and Boylston with trouble, at the same time next year. It was that demand, and his family’s trust in me, that snatched Spenser out of limbo and put him back to work, not just a simple-minded and craven cash grab by publishers. If fans did not want Spenser to return, Robert B. Parker’s Lullaby would not have remained on the New York Times bestseller list for nearly two months. I still have not been able to respond to the hundreds of letters I’ve received from grateful fans writing of their personal connection to the series.

Joseph Campbell said it best when he explained that heroes do more than any spiritualist or guru to help us navigate confusing or troubled times. Society needs heroes. They live deep within our consciousness, bringing comfort and understanding. Perhaps that’s why, 50 years after the first James Bond film, Bond seems even more relevant in a post-9/11 society. Jones singles out novelists for the crime of revisiting classic characters; films earn a pass from him as a different medium.

With Spenser, I fully expected an avalanche of criticism from Parker’s fans, critics, and students of the genre. But writing Spenser was a job that I wanted anyway. As a veteran crime novelist, Parker’s work had meant to me what Chandler’s had meant to him. My career, writing style, and social outlook had been based on his work. I took on the job because, like his fans, I personally did not want the series to end. The stories were about far more than murder and violence. They’re about self-reliance, morals, and tolerance of all races and sexual orientations. Maybe that’s what makes Spenser timeless, what makes us return to him year after year.

Mostly, I knew Spenser had a lot more in him. As a novelist, I saw the potential for a proper, respectful, and exciting way it could work. If not, I would not have taken on the challenge. I do not seek out the redundant, the pastiche, or the formulaic. I only sought new, unique stories for a great hero.

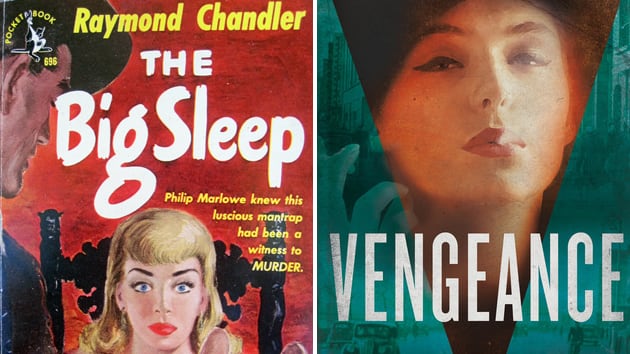

I found Parker wrote with the same passion when completing Chandler’s unfinished Poodle Springs. At this time he took on Marlowe, Parker was a major bestseller who did not need to be put under the microscope. And although hardened Chandler fans might point out picky details, Jones is the first I have heard describe Parker’s take on Marlowe as “execrable” and “laughable.” I also disagree that Bogart was only OK as Marlowe in The Big Sleep. It’s Bogart!

Most pointedly, Jones writes that only in death did Parker get what he deserved for his Chandler sins by “someone now doing the same thing to him.” Is it really an insult to have a massive fanbase clamoring for more of his creation after the author has left this earth? I feel it’s the ultimate compliment to the series author that his or her character has reached that rarified, iconic status. Bookshelves are filled with endless—mostly nameless—heroes but very few that become part of the American consciousness.

In fairness to Jones, I am not a fan of anyone trying to reinvent the author’s vision of their character. For that reason, I have yet to read Jeffery Deaver’s James Bond novel with Bond now a veteran of the Afghan war who does not smoke. But I did appreciate and respect the careful way John Gardner continued 007 in the 1980s. He was the perfect author for the job, a well-respected British thriller writer with a solid idea of how to update the character to the time while keeping Fleming’s original vision firmly intact. I also look forward to reading William Boyd’s forthcoming novel taking Bond back to 1969 and the Cold War.

Jones dismisses all these conceits and incorrectly calls them “endless sequelizing.” But a sequel most often means another look or furthered take on the same story, not new adventures and new stories of a character. Chandler’s The Little Sister is not a sequel to The Big Sleep, and neither was Kingsley Amis writing Bond in Colonel Sun or whatever Banville might invent for Marlowe. Parker did not write one Spenser novel and 38 sequels. He invented a character and a world for him to inhabit. Jones outright dismisses any new writer who might dare tell more tales of an established character. Perhaps Thomas Mallory should have left well enough alone with the original French Arthurian tales. Iconic characters like Marlowe, Spenser, and James Bond make up the patchwork of our modern day folklore. They exist outside of their original stories, beyond the confines of the page.

Do we really want to place our icons in glass cases after their creator’s death and deny fans the pleasure of reading new adventures of characters they love? If done well and properly, it benefits not only publisher coffers but the reading public as well. So with permission of Bob Parker’s wife, two sons, longtime editor, and legions of fans, I’m happy to remove any do-not-disturb sign off Spenser’s office door.

There are thousands and thousands of heroes in literature, but too few great ones that stay and live with us. Cheers to the ones who do. And the best of luck to Mr. Banville and my old friend Marlowe. From one private-eye writer to another, watch your back. They’re gunning for you.