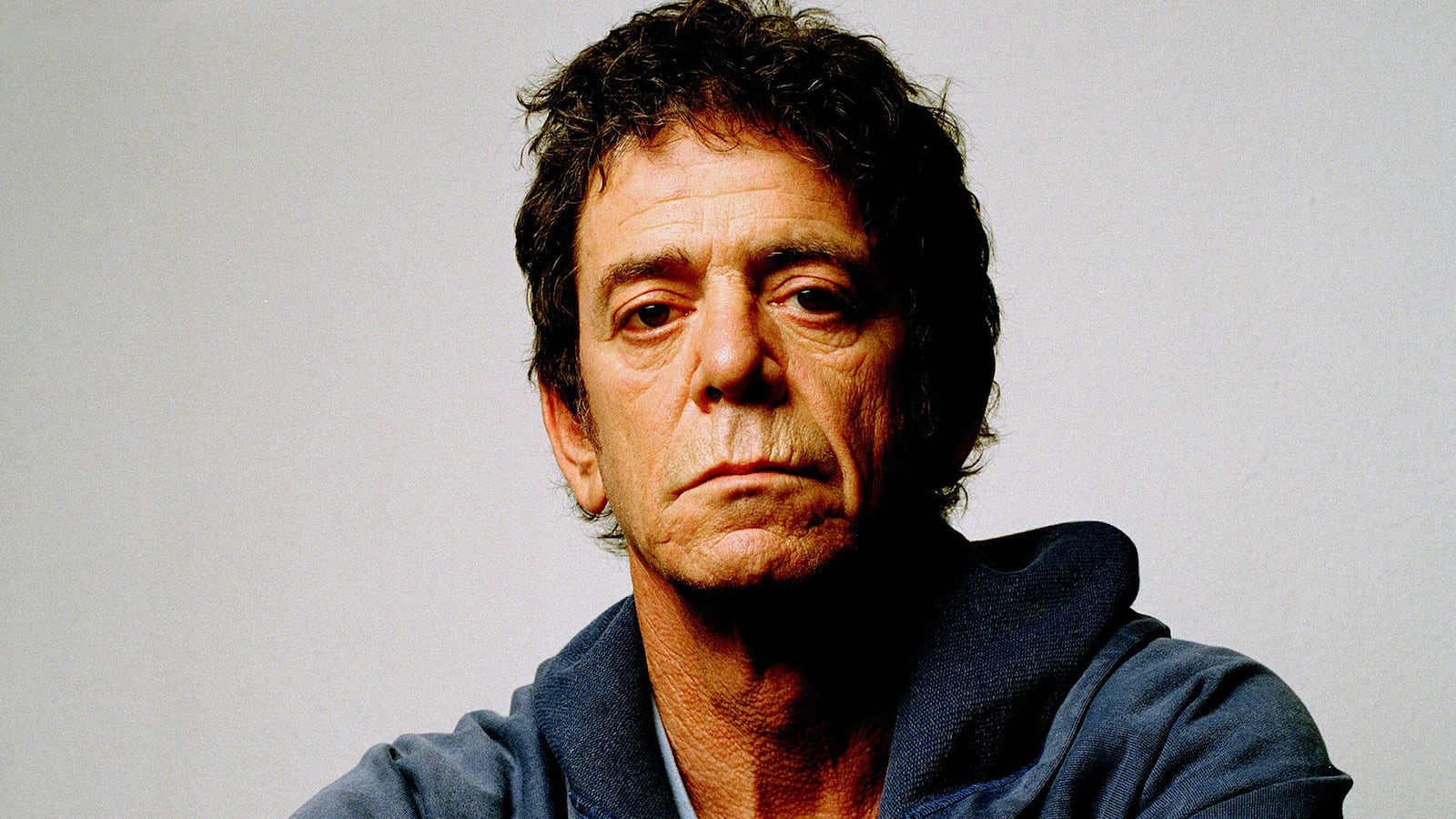

If you’ve ever entered into a debate with a fellow music nerd about the enormous contribution Lou Reed and the Velvet Underground have bequeathed to late 20th century popular culture, within a few minutes the following cliché is likely to have surfaced : “The Velvet Underground & Nico only sold a few thousand copies, but everyone who bought that record formed a band.”

The conversation most likely took place in the early hours of the morning, where copious amounts of alcohol, amphetamines, and marijuana were simultaneously consumed.

You were probably young, impressionable, naïve, and it’s extremely plausible during this precise moment—when ‘Femme Fatale’, ‘Sunday Morning’, and ‘Run Run Run’ were blasting from a record player, on repeat, for several hours, in a premises you couldn’t quite remember how you had arrived to—you were convinced your words were one day going to profoundly change human civilization for the better.

But alas, you woke up feeling hungover, disillusioned, and alienated.

Growing up as an awkward, neurotic, and slightly anxious teenager in Dublin in the late 1990s—when Catholicism was only beginning to relinquish its fascist-like-dominance over Irish society— the records of The Velvet Underground and Lou Reed allowed me to momentarily escape into a world that seemed to say, with dead-pan-coolness : the rules are there are no rules and the establishment can go fuck itself.

Listening to this music was about more than songs and melodies. In a way, it sort of formed one’s identity. When you discovered someone at a house party who held a faded copy of The Velvet Underground & Nico, VU, or Transformer in their record collection, you understood they meant business. Even though Lou Reed was supposed to be the coolest motherfucker on the planet, his fans always struck me as slightly nerdier, than say, your typical Beatles, Stones, or Pink Floyd fan.

When these geeks weren’t up for two-days-straight talking gibberish, fueled by cheap ecstasy pills , it seemed more likely you might run into them at the library on a rainy Thursday afternoon, studying Brecht, Tolstoy, Joyce, or Dostoevsky.

Beneath their fake bravado nonsense, and leather jacket smugness, usually lay an intelligence that required considerable sensitivity. A real Velvet Underground fan was no dilettante.

Of the numerous women who have come and gone in my life, I’ve somehow always managed to relate the Dionysiac moments with each of them back to the Velvet Underground and Lou Reed.

While much of this music tends to fall into the existential-destructive-chaotic section of the record shop, there is a plethora of placid songs in the back catalogue for us hopeless romantics too.

Whenever I hear the nursery-rhyme-like-simplicity contained within numbers such as, ‘I’m Sticking with You’, ‘Satellite of Love’, ‘Stephanie Says’, or ‘ Pale Blue Eyes’, I invariably find myself returning to a recurring memory: I’m lying in bed with a beautiful woman who has perfectly straight long black hair, the most enormous eyes you’ve ever seen, and a wonderfully smooth dark complexion. In the background, Lou’s soothing voice is effortlessly serenading both of us. For a fleeting moment, it appears that perfection can indeed be achieved in this universe.

At the impressionable age of 19, I arrived to New York City from Dublin for the first time.

Lou Reed and The Velvet Underground became the soundtrack to my epic adventure that summer. I spent each evening collecting dirty dishes as a busboy in a steakhouse frequented by rich city stock brokers, in Montauk, Long Island.

I would return every night to a run down room in a small bungalow at the edge of town I was renting with my then girlfriend. In a disused shed in the back garden that overlooked a lake, my friend and I would get exceptionally stoned: always listening to the chaotic chants of The Velvet Underground.

One August evening, that seemed to stretch on into dawn, an epic thunderstorm storm broke out. As purple forks of lightening shattered violently across the sky, and a great cacophony reverberated over the lake, and out onto the wild Atlantic ocean, ‘All Tomorrow’s Parties’ seemed to provide the perfect backing-track for the apocalyptic weather that raged for hours. The more delusional my friend and I became, the conversation would inevitably return to the genius of John Cale’s fusion of guitar and tone clusters on the piano: as Nico’s angelic voice created a fitting equilibrium to match both instruments.

We both worked out, in between fits of laughter, and prolonged-paranoid-silences, that it was exactly 95 miles to Freeport, where Lewis Allen Reed, a deeply troubled son of two rich Jewish tax accountants, had spent his youth. We sought consolation in the fact that, even though the distance was considerably large from where we were living, technically, we were on the same island Lou had grown up on.

I imagined the trepidation young Lewis must have felt when his parents dragged him to Creedmore State Psychiatric Hospital, where the staff put electrodes on his head: attempting to exterminate what they believed to be devious sexual compulsions.

Lou Reed’s biography is memorably sad, but without this melancholy narrative, it’s highly unlikely the songs that later arose from this traumatic adolescent experience would have ever materialized. Most brilliant art usually arises out of some sense of insecurity from the individual. Thus the words displacement and Lou Reed would always be inextricably linked from the moment he picked up a guitar.

In June 2008, when I returned again to live in New York— this time working for a radio station — I made the pilgrimage several times to the exact spot on the intersection where I imagined Lou had stood waiting for his dealer on Lexington Avenue and 125th Street.

I would regularly insulate myself from my temporary New York loneliness with a very simple thought: Lou once stood here too.

That same summer I went to see Patti Smith give a talk in Film Forum in Soho, after a debut screening of Dream of Life. Much of the biographical documentary takes place in the Chelsea Hotel during the early 1970s. I asked Smith after the show what the difference was between writing rock-lyrics and poems. “When you are writing poetry, man,” she answered: “ You are thinking of William Blake and the God’s. With songs though, you are fitting it all into a grander narrative structure that accompanies the music”

I wondered would Lou have agreed? He was probably practicing yoga or Tai Chi somewhere in his apartment, which was only a few blocks away. After all, without Lou, Patti mightn’t be here today, I thought to myself. There seems to be a direct trajectory from the early 1970s onwards, where all rock music of a certain creed descends from Lou: Patti Smith, Television, Blondie, The Ramones, The Sex Pistols, The Clash, U2, Talking Heads, The Jesus and Mary Chain, The Smiths, John Cooper Clarke and The Fall. All of them spoke about art in a similar non-conformist manner when they began their careers. But most of them failed to properly emulate what Lou seemed to always embody without even the slightest ounce of effort.

I was in my basement flat in south east London on October 27, 2013, when I heard Lou Reed finally passed on into the ether. From the amount of poison he had ingested into his body over the decades it was surprising he lasted as long as he did.

A good friend of mine messaged me immediately on Facebook that Sunday evening.

We began emotionally recalling endless afternoons we’d spent after school as teenagers, dissecting, for hours at a time, how John Cale’s pitch-perfect Welsh accent matched effortlessly with the rhythm section from a track off White Light /White Heat called’ The Gift’: a musical short story that Reed had written during his college years. It involves a paranoid love-sick Waldo Jeffers, who mails his own head to his college sweet heart, Marsha Bronson. I always loved the way Reed managed to keep the listener guessing until the very last line about what exactly was contained in that very large envelop.

If I was to attempt to put my finger on why The Velvet Underground and Lou Reed’s music meant so much to me, and many of my peers—particularly in our most formative and difficult teenage years— I believe it has something to do with the importance the songs place on creating a mythological world: where outsiders assume leading roles and conventional society, as we normally conceive it, suddenly disappears.

Growing up, fitting into the mould of what was deemed “normal” seemed to me to be a terribly painful experience: where achieving acceptance status required one to do a-hell-of-a-lot of pretending. Lou Reed and The Velvet Underground turned that idea completely on its head. If there was a rule book on middle-class-values, they tore it to pieces and ate the remaining shreds of paper.

Geeks, freaks, queers, drag-queens, drug-addicts, pimps, whores, hustlers, loan sharks, and only those who operate by the rule of the street, suddenly become a powerful force to be reckoned with. Massage parlours take the place of corporate offices and churches; while drug dealers and sadomasochists assume the respectability of mainstream citizens. The subterranean world of the gutter opens up from dull monochrome, to suddenly illuminate into several bright shades of technicolor brilliance.

I suspect this compelling form of storytelling comes from the importance Lou Reed always placed in his songwriting on narrative structures. At first glance, tracks like ‘Perfect Day’ or ‘Sunday Morning’ always seem incredibly simple. But dig beneath the surface, look closer: there is a whole world of nuance working its way though this incredibly complex artistic vision.

The hidden genius contained within this music is that these songs move you on a visceral level. And if there is an intellectual mechanism at work, you barley even capture it in your rear-view mirror. The key to all good songwriting is feigned simplicity. And Reed was an absolute master of this particular trick.

In an interview he gave to the British writer, Neil Gaiman, in 1992, Reed confessed how he tried to bring a “novelist’s eye within the frame work of rock and roll” into his song writing.

In a fascinating discussion he conducted with Spin magazine in 2008, Reed was asked if there was a moral aspect to a song like ‘Heroin’: where the singer claims he feels like Jesus’s son after he puts a spike into his vein. Reed responded ambiguously to the question by claiming he was:

Writing about real things. Real people. Real characters. You have to believe what I write about is true… Sometimes it’s me, or a composite of me and other people. Sometimes it’s not me at all.

In Lou Reed: The Last Interview and Other Conversations, a concise but marvelous new book that contains six of these lengthy interviews in total, we see a pattern developing: As Reed got older, he mellowed out, and his appetite for drugs and booze waned considerably. We see him in his latter years, slightly ashamed of what he even referred to in one song as “growing up in public/ with your pants down.”

The great social taboos that Reed tackles in his song writing —drug addiction, sexual deviance, and a penchant for lowlifes and down and outs— percolates down from an artistic style that came to fruition during the 1950s, from a literary movement that affectionately became known as The Beat Generation: where authors like Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Jack Kerouac, Lawrence Ferlinghetti , and others, rejected conventional bourgeois American values. Celebrating instead a subculture of street merchants, thugs, pornographers, tough guys, beatniks, sailors, sex-fiends with ravenous libidinous desires—often of a homosexual nature— whose main purpose in life was to take drugs, write, talk about artistic ideas, and explore a decadent world of pleasure that was nihilistic and bordering on the sadistic.

In the recently updated Waiting For the Man The Life & Music of Lou Reed, the English poet and author, Jeremy Reed—no relation to Lou— attempts to fuse biography with a kind of academic assessment of the singer’s career, connecting the themes that crop up in his work to the cult authors I’ve just mentioned.

“My interest in Lou Reed,” the author explains in the opening chapter, “focuses partly on his singular concern to turn rock into an intelligently literate medium of expression.”

There is more than a serious grain of truth contained within this statement. But the question one must ask themselves, before embarking on this reading journey is: do I need a whole book where the subject is forcefully rammed down my throat?

The narrative is essentially a work of comparative literature. For every Lou Reed lyric mentioned here we get an analogy to William Burroughs’ stream-of-consciousness prose, paragraphs describing the abstraction contained with John Ashbery’s poetry, or long passages about the free living sensibility that can be found within the work of Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady.

The book was originally published in 1994, and this updated version, it appears, has been brought out to cash in on the interest that has inevitably come about since Lou Reed’s death.

I found Jeremy Reed’s style of writing, however, to be extremely scattered, overindulgent, pompous and exhausting. George Orwell’s observation that “the great enemy of clear language is insincerity,” immediately comes to mind.

There is no sense of order to Reed’s prose, which pollutes the page like a badly planned modernist novel. He then goes off on daft tangents, where he over intellectualizes every single lyric of Lou Reed to a point that is just farcical.

Most of what is actually contained here about Lou Reed’s personal life we knew already: he had a sexual preference for transvestites ; he was a misogynist; he could be a real ass-hole to his audiences at times; he struggled with addiction and substance abuse for a number of decades, namely, heroin, speed, and alcohol; and he married three different women at numerous stages of his life, somehow hoping one of them might make him a semi conventional straight guy, but never really did in the end.

The only bit of originality the author offers are academic-style opinions of Reed’s music; while all interviews we come across here are gleaned from other music journalists.

After reading the book, I went back to many of the original interviews and felt I got more out of them, than reading Jeremy Reed’s second hand analysis, which makes numerous outrageous claims. Allow me to indulge you in one of them: “Lou Reed was assumed to have out-gayed gays and out-punked punks and out-drugged druggies as an infamous intellectualized Judy Garland of the gutter.”

The author then asks the reader—as if they were participating in some undergraduate cultural studies music module— to take part in discussions about the nature of pop music itself.

These have nothing to do with the subject of Lou Reed’s music or lyrics. Here is one egregious example:

There’s a real argument to be considered that rock music, like good poetry, by its economic phrasing and fractured narrative leaves mainstream fiction obsolete.

It’s a very dodgy practice when authors begin over-intellectualizing, at great length, the words and motives of rock stars. And the style of writing that Jeremy Reed indulges in here reminded me of another poor biography I reviewed last year about Leonard Cohen, called A Broken Hallelujah, by Liel Leibovitz.

Like Jeremy Reed, Leibovitz similarly indulges in this pompous game of trying to create a cultural studies department for aging rock stars. In the process, the beauty and mystery of the artists’ words become almost like a mathematical formulae that’s meant to be deconstructed down to nothing. There is very little merit created in this critical process.

There has always been an appealing quality contained within the central ethos that rock n roll was formed on that seems to unconsciously upset certain critics. Primarily because despite their continual frustrated attempts, they cannot seem to deconstruct this mystical musical genre in the same way as they can do with say, a novel, a poem, or drama.

And—I say this as a professional critic myself— there is something incredibly liberating and beautiful about this fact.

It’s no coincidence that rock music has always seemed to be able to naturally portray feelings about sexual liberation, or expression, in a far greater capacity than anything literature can even get close to.

And sure, Lou Reed has, as I have suggested, several times in this piece, certainly brought a level of intellectual coherence to his song writing, that many before, and after him, could never match or equal.

But if you really want to understand the music of Lou Reed, and The Velvet Underground, experience it directly. And leave the overindulgent analysis to one side for the time being.

Instead, live and breathe the absolute totality of the music.

Go to a party, make love, get high or drunk, while simultaneously studying its multiplicities of meaning. Stay up all night, and let Lou Reed take you to places you might never imagined we’re possible.

Feel that bass line take control of your whole being: it will automatically warn you that’s its far too early to go home at this unreasonable hour. Let distortion corrupt your moral compass for fifteen minutes. Ignore your intellectual grounding for once in your life, and follow your primordial impulses at all costs.

Hurry up, the music is getting louder. And don’t worry, a jaded monotone New York drawl will dictate events from here on in. Forget questions like how, why, and who with? Just allow the rhythm to give you direction and move with it.

Lou, in his own idiosyncratic way, is now in observation mode. And he’s explaining, very subtly, that: “She’s Over by the Corner/ Got her hands by her side.”

Start listening closely. Because pretty quickly, everything else should fall into place. And things will somehow magically begin to make perfect sense from here on in.