Donald Trump has already found that mixing electoral politics with owning a Washington hotel can be tricky business. The Trump International Hotel should have been a triumph—the swanky new establishment is, after all, in one of the most beautiful buildings in Washington, a romanesque monument from 1899 that had been known as the Old Post Office. But instead, Trump’s candidacy has made the hotel a source of controversy and a object of protest.

Celebrated chef José Andrés—disgusted with Trump’s remarks about immigrants—bailed out of plans to open an extravagant restaurant in the new hotel. (Andrés is just one of the restaurateurs to quit Trump International, leading to a raft of litigation.) D.C. Council member Charles Allen tried this summer to have Trump’s name stricken from signs on the building that read “Coming 2016/TRUMP,” accusing the candidate of surreptitious political advertising. And since the hotel opened in September, it has become a target for “Black Lives Matter” graffiti.

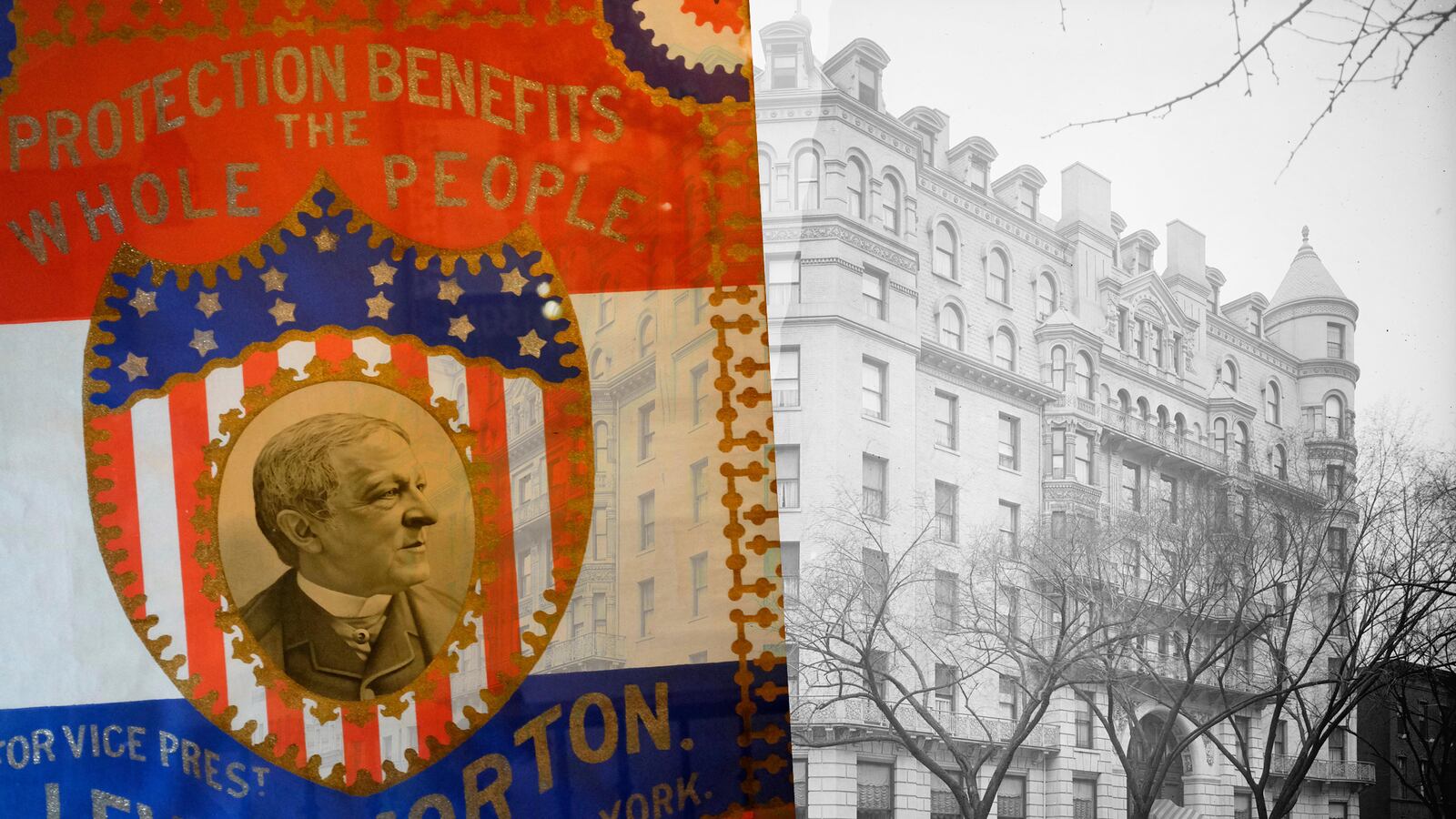

But, if it’s possible to imagine it, the Trump International brouhahas are not even close to being the most vitriolic response to a hotel opened by a national politician. Trump’s critics have nothing on the prohibitionists who outraged when Vice President Levi P. Morton opened a Washington hotel at which liquor was sold.

“Does history record such a national disgrace as a dram-shop maintained by the next highest official in the Government?” thundered H. Clay Bascom at the national Prohibition Convention held in Albany, September 1891. President Benjamin Harrison had entered the White House in 1889, and early in his administration, Harrison’s veep completed and launched the elegant Shoreham Hotel in Washington.

In that hotel was a restaurant and bar; the fact of the latter drove the nation’s prohibitionists nearly to distraction. Morton had “opened the first vice-presidential dram-shop that this country has ever maintained,” Bascom sputtered. “With its large varieties of intoxicants it continues in deadly blast to decoy and destroy the goodly youth of the land.”

How big a variety of intoxicants? A prohibition pamphlet titled “The Saloon a Nuisance and License Unconstitutional” sneered that Morton’s “first-class hotel” contained “a first-class saloon, with a first-class bar, eighty feet long, from behind which forty-four brands of intoxicating drinks were sold.” The Pittsburgh Times, in an outraged editorial titled “Our Liquor-Selling Vice-President,” went into even more detail: At the Shoreham “there is for sale five varieties of whiskey, two of rum, two of brandy, and twenty-five brands of wine. Surely this is enough to satisfy the most variegated appetite for intoxicants.”

The Pittsburgh Post reported that liquors were served at the Shoreham by “a full staff of white aproned and Cape May diamonded bar keepers,” who did “a rushing business.” The paper suggested that, at the Shoreham, one should call for a “Morton cocktail” or a “vice presidential gin sling.” If such drinks were ever concocted, they are lost to time.

W. Jennings Demorest, leader of the liquor-hating Anti-Nuisance League, contrived a new idea for how to shut down the country’s bars and saloons and made the Shoreham his first, high-value target. “We are going to inaugurate a campaign against the liquor traffic which will take people’s breath away,” he proclaimed. The idea was to find individuals who had “suffered injury by reason of the sale of liquor,” and then have them sue “the most prominent liquor men in the country.” And there was no question in his mind who the most prominent liquor man in the country was.

“Our plan was to begin the crusade in the City of Washingon,” Demorest said, “by securing an injunction against Vice-President Morton” as the “abettor of a nuisance.”

But then, just as the Anti-Nuisance League was ready to make a nuisance of itself, something strange and remarkable happened: Part of the fashionable Shoreham hotel collapsed.

It seems that, when the hotel was built, workmen had mixed mortar, not in wheelbarrows, but right on the wood floors in a stairwell. As one newspaper recounted it, “lye had formed and soaked through to the rafters and floor supports, which had rotted away.” The staircase—in a hotel only two years old—gave way and smashed down several floors all the way into the cellar. Remarkably, no one was killed.

One might think that the prohibitionists would have been delighted, perhaps seeing the collapse as a divine judgment. At the very least one might expect them to have been pleased that, for a while, no demon rum would be slung at the Shoreham. But no. “We were quite annoyed when we heard of the accident,” Demorest wrote, “because we wanted to begin our work in Washington.” He comforted himself that “the repairs in the Shoreham are progressing rapidly, and the hotel may be opened when we commence our campaign in earnest.”

It would be three decades before the prohibitionists, with the 18th Amendment to the Constitution, managed to shut down what they had called “Morton’s Saloon.” The old Shoreham hotel didn’t outlast Prohibition—it was razed in 1929. The next year a new Shoreham hotel was opened uptown. It’s still there, now officially the Omni Shoreham.

One hopes the bar there might come up with a Morton cocktail to serve in honor of the man who gave the hotel its start, and who—as the forces of prohibition saw it—put the vice in vice president.