It was early morning on May 10 when the control room went dark aboard a research vessel drifting through one of the deepest points in the ocean. Transmissions from Nereus—the deepest-diving of the few unmanned deep-sea exploration vehicles in the world—would never reach the surface again.

Though these kinds of expeditions are precarious and costly, discoveries made miles below the surface of the ocean have proved worthwhile—like Nereus finding a new potential treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. Now, in the wake of the rover’s loss, scientists are no longer able to reach the ocean’s trenches, leaving the promise for combating pressing global health and environmental concerns out to sea.

A sense of dread that Nereus would not be able to complete its latest mission to explore life in the Kermadec Trench set in as a team of 30 scientists waited for the $8 million vehicle to resurface. Hours later, scraps of white plastic dotted the ocean around the vessel’s coordinates—Nereus had returned in unsalvageable bits.

“It was a horrible feeling of denial and disbelief,” says Timothy Shank, deep-sea biologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) and chief scientist on the expedition.

The rover’s destruction left a massive void in scientists’ ability to study the hostile environment, and it’s not the first to have gone down. It joins a list of five deep-sea exploration vehicles that have been lost or near-fatally damaged on the job since 2003. They went AWOL all around the world—from the waters around Antarctica to just off a Japanese Island—for a host of reasons. Still, the secrets contained in the least hospitable parts of the ocean reveal why sending millions of dollars of machines after them is worth it.

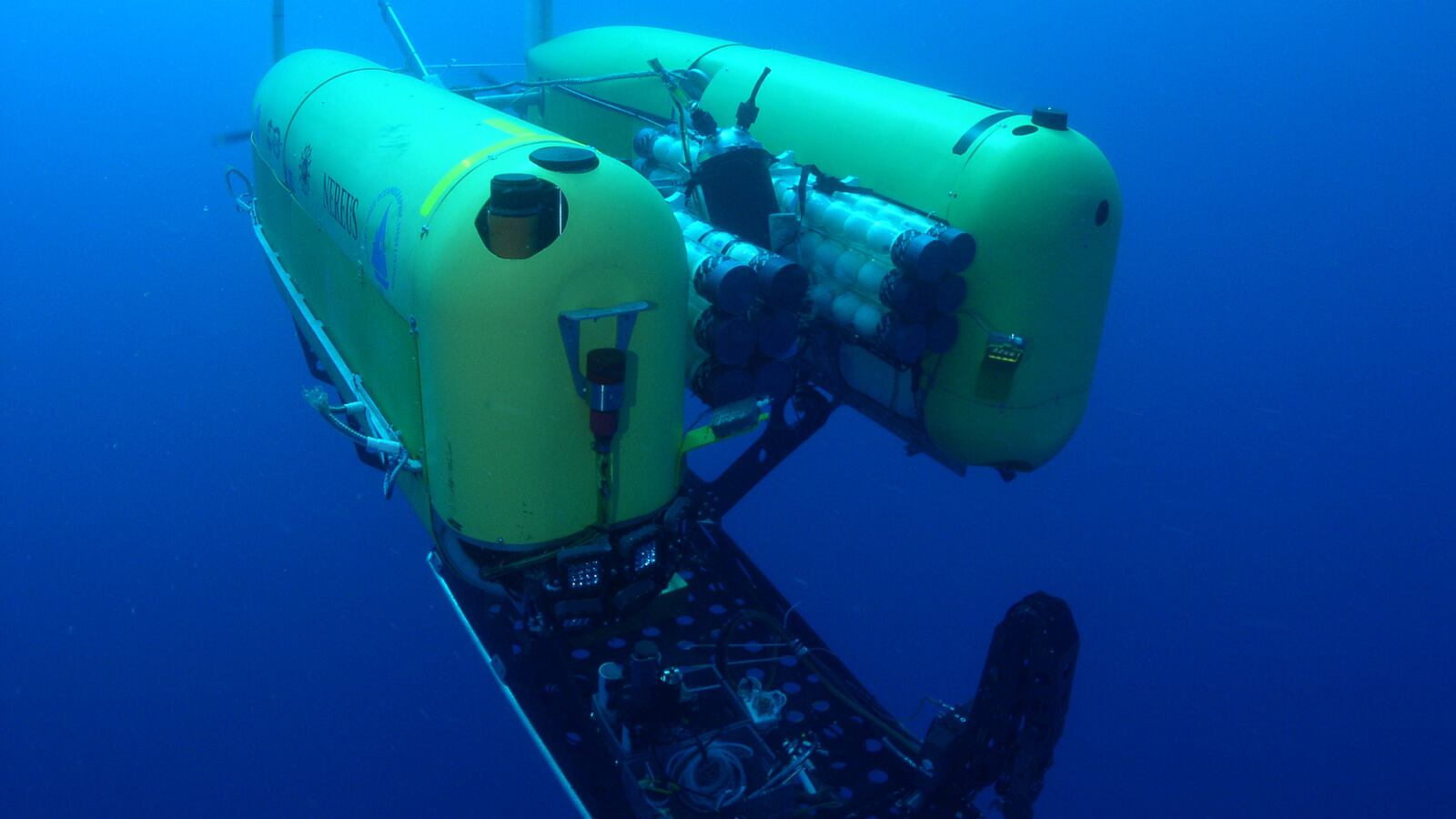

Nereus was named for a mythological Greek god with a fish tail and a man’s torso. It reached the lowest point of the Mariana Trench in 2009, which is thousands of meters lower than Mount Everest is tall. When it surfaced, it brought with it organisms which showcased the remarkable adaptations of life in some of the deepest, darkest places in the world. Not long before it was destroyed, Nereus had delivered polychaete worms and two sea cucumbers from several miles below sea level, which will be studied to determine how these animals have adapted to such dark, cold, and hostile habitats.

And the enzymes found in some organisms Nereus collected from the ocean’s deepest parts are being tested as possible treatments for Alzheimer’s disease. A particular osmolyte, or solute that helps water-based life maintain the structure of cells, found in deep sea crustaceans is proving promising in dissolving the plaque that builds up around nerve cells in the brain to cause the disease. Scientists believe that the solute was developed in deep-sea organisms to combat the pressure found in the ocean’s depths. Clinical tests have found that the osmolyte both prevents the onset of Alzheimer’s and treats its symptoms.

Researchers are also exploring how deep-sea trenches bury carbon and other chemicals in the seafloor. Studying how this process works and under what conditions is important to scientists exploring ways to mitigate the effects of climate change.Marine biologist Jonathan Copley writes, “The loss...is utterly crushing for those aboard a research expedition and their colleagues ashore. But whenever we send something into the ocean depths, there is never an absolute guarantee that it will come back.”The last deep-sea exploration vehicle to go down before Nereus was the Autonomous Benthic Explorer (aka ABE), which scientists believe also suffered a catastrophic implosion. After carrying out more than 200 deep-sea dives to map hydrothermal vents and oceanic volcanoes, the vehicle was lost off the coast of Chile in 2010. Another, Autosub-2, was trapped as it explored life beneath permanent ice shelves around Antarctica in 2005. And in 2003, a remotely operated underwater vehicle (or ROV) named Kaiko was destroyed as a typhoon spread over the area around Japan, where it collected sediment and organisms for research.Copley, who is based at Southampton University in England, writes in a blog post that these losses happen despite the most intricate of planning efforts. “It sometimes seems like we have more contingency plans than there are letters in the alphabet,” he claims.While its remains have yet to be conclusively examined, scientists believe Nereus imploded from the pressure taken on at such a depth—about 16,000 pounds per square inch. Built in 2008, Nereus featured completely new technology to meet the unique challenges of deep-sea exploration. Shank explained that its possible continuing wear compromised its structure and caused it to buckle, despite all that new technology.

As for potential replacements for Nereus, Shank doubts there are any vessels that could effectively do the same kind of research so deep in the ocean. A third of the ocean can’t be explored without it, Shank told Ira Flatow on a recent episode of Science Friday. “And so we absolutely have to have another one, if not many more.”

While the loss of Nereus may mean an end of its unmatched study of the sea that has engendered new and important research, for some, it’s more personal than that. “I feel as if I have lost a child,” Casey Machado, who headed up the latest Nereus expedition, wrote on WHOI’s Facebook page. “I’d greet Nereus each morning on deck and wave goodbye to her as she was released to her long commute down to work each dive. She will be missed greatly.”

While many scientists who worked with Nereus are still in a state of mourning, replacements are on the way. WHOI is working on a small fleet of Nereus-like vehicles called Nereids, which will take on ocean exploration at different depths and by different means. One will utilize a hybrid tethering system, one will explore under sea ice, and still another will be able to reach the depths that Nereus achieved.“The plans are already underway,” Shank told Flatow, though the price tag is daunting—along the order of $15 million to $20 million. But compared to other pieces of equipment, that’s nothing. “[That’s] maybe a million shy of a single Black Hawk helicopter, of which we have thousands in the U.S.” he said.

The Nereids could continue our exploration of the deep, push the limits of what we know about our planet, and bring back cures for diseases. To Shank, that’s worth giving up one military helicopter.