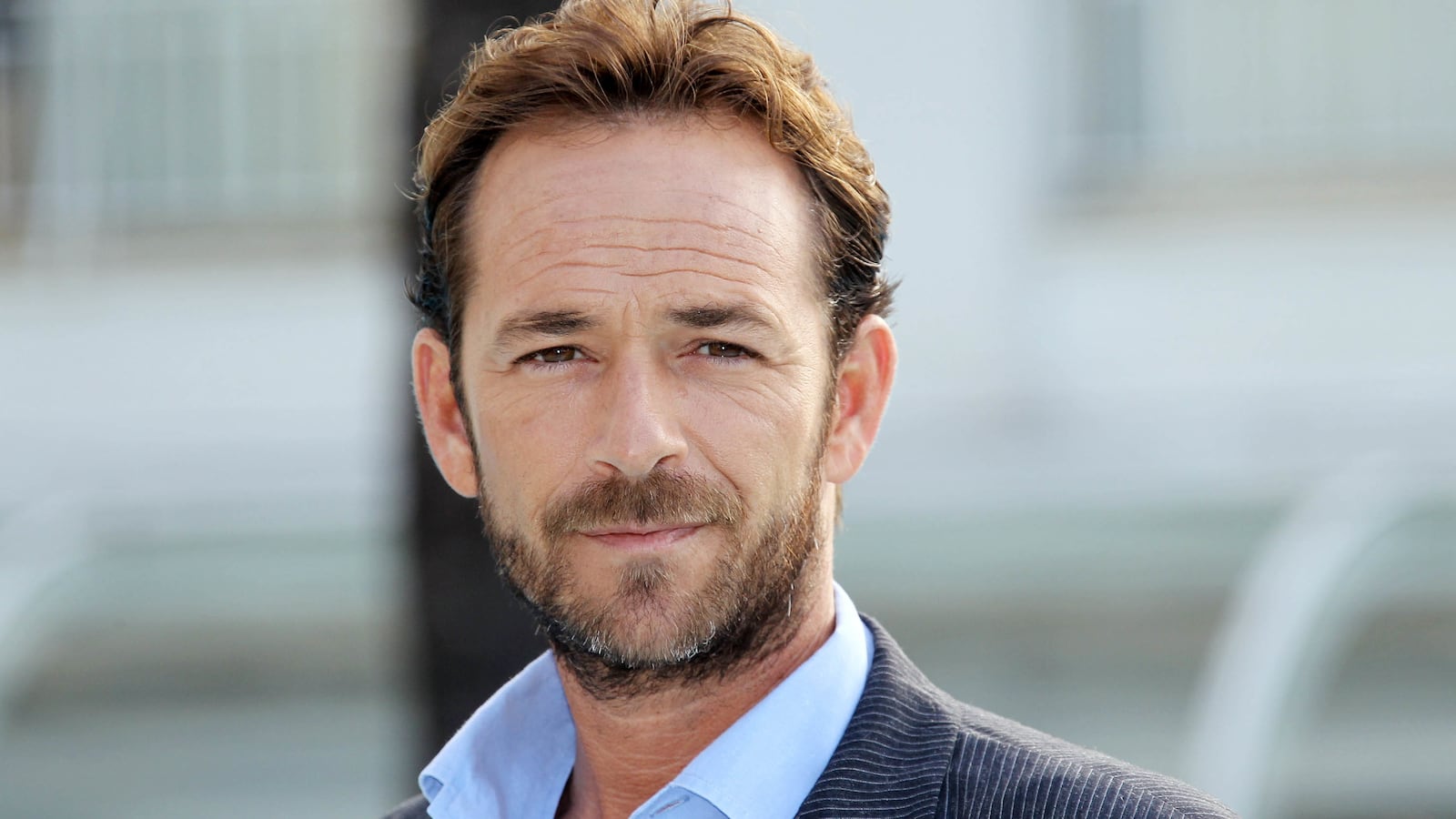

Actor Luke Perry’s death from a massive stroke at the age of 52 highlights how quickly they can strike, how deadly they can be, and how they are killing more and more young people.

Steven Zeiler, an assistant professor at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institute in Baltimore and the director of the school’s cerebral vascular fellowship, said that Perry’s age, though shocking to fans, is “not necessarily out of the range of normal.”

Statistics back him up. A 2012 study in Neurology found that the average age of stroke in patients in Cincinnati decreased from 71 in the 1990s to 69 in 2005. Those younger than 55 made up about 13 percent of all strokes in the 1990s, but that number had jumped to about 19 percent in 2005. And according to the Centers for Disease Control, nearly 34 percent of people who had a stroke were younger than 65 in 2009.

Initial reports described Perry as suffering a “massive” stroke on Wednesday, though that doesn’t explain exactly what type of stroke he had.

Anything that cuts off blood supply to the brain can cause a stroke.

There are thrombotic strokes, which happen when blood vessels get clogged with what Zeiler referred to as “gunk” caused by age, obesity, diabetes, smoking, hypertension, and high cholesterol.

“You might have heard of people having a carotid stent placed,” he said. “That’s an intervention designed to prevent that gunk from building up to a dangerous degree.”

A blood vessel in the brain can also rupture, which is known as a hemorrhagic stroke, often caused by uncontrolled high blood pressure.

A third type is the embolic stroke, in which a clot gets trapped in a brain artery; these clots can be caused by irregular heart rhythms or heart failure that slows blood pumping.

Zeiler’s colleague, assistant professor Mona Bahouth, said that when the word massive is used in connection with a stroke, it usually refers to the size of the affected vessel.

“It’s like if you had an accident on 95 and it was completely shut down, you can imagine traffic into New York would get affected,” Bahouth said. “That, versus a small side street getting blocked. You’d still have issues, but not quite that much.”

Perry survived five days after suffering from his stroke, which experts say is not unusual. Zeiler likened it to knocking against a table: “You won’t get a bruise right away, but it gets really big a couple days later when you get inflammation,” he said. “That’s the same with the brain.”

Zeiler said that while genetics plays a role in strokes, “prevention is the best medicine.”

“Take care of your risk factors: Eat healthy, exercise, control your diabetes, don’t smoke,” he ticked off.

“We’ve made great strides reducing frequency from death from stroke,” Bahouth added, pointing out that stroke has dropped from the second leading cause of death to the fifth in Americans.

“We’ve gotten better at recognizing signs of stroke and intervention. We’re doing well at reducing disability related to stroke,” she said.

Yet, despite the advances in detection and treatment, “probably on the order of 15 or 20 percent of patients die.”

Because it’s so difficult to predict when strokes will happen, researchers have focused on treating them.

The biggest factor is immediate medical attention. That’s why the medical community came up with the acronym FAST to alert the public to stroke symptoms: a droopy face, arms that become weak, slurred speech, and time.

“The earlier you get to the hospital the better,” Zeiler said. “There are lifesaving and stroke-altering therapies that can be offered but can only be offered in time. Delaying is a horrible thing to do. Some people think they can sleep it off, but that can sometimes be too late.”

Bahouth agreed.

“Stroke is one of those devastating diseases where one minute you’re feeling fine, and in just a second, symptoms come on,” she said. “If you feel symptoms like sudden weakness, sudden loss of vision, and trouble speaking, go get evaluated quickly.”