The Trump Organization’s two affiliate companies on trial in New York City were found guilty of all nine counts of tax fraud and related crimes on Monday, as jurors ended a long trial with a swift verdict against the former American president’s corporate empire.

The Manhattan jury concluded that former President Donald Trump’s eponymous companies dodged taxes by playing accounting games: showering their executives with benefits, reducing their official salary, and paying them at times as if they were “independent contractors.”

As the court clerk read the list of nine criminal counts—tax fraud, falsifying business records, engaging in a conspiracy—the jury foreperson kept repeating the same word, "Guilty." At times, she even got ahead of herself, saying the word before the clerk finished describing the charge. Afterward, each juror nodded and asserted out loud that they agreed.

The company now faces what prosecutors expect to be more than $1 million in fines—a paltry sum for a multi-billion dollar global marketing operation but a mark of shame nonetheless, just as Trump launches a re-election campaign. This is also the first successful legal action against the Trumps in years.

The tax accounting hacks were all a ruse—one that even the company acknowledged but placed all the blame on a rogue employee.

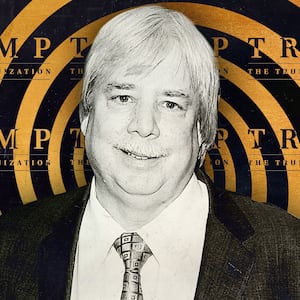

Defense lawyer Michael van der Veen tried to win over jurors with a mantra straight out of the O.J. Simpson trial: “If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit.” The Trump Organization motto was, “Weisselberg did it for Weisselberg.

But the jurors weren’t convinced. After all, those swindling staffers were Chief Financial Officer Allen Weisselberg and company controller Jeffrey McConney, as well as half a dozen other executives who were never charged.

Weisselberg eventually confessed to reducing his on-the-books salary—allowing him to avoid city, state, and federal taxes—and instead got an ton of perks: a fake $6,000 no-show job for his wife, corporate Mercedes sedans for them both, a luxury Manhattan apartment, and more than $360,000 in private school tuition for their grandkids paid by Donald Trump himself.

Weisselberg and several other executives, including Chief Operating Officer Matthew Calamari Sr., also diverted some of their salary to make it seem as if they were outside contractors, claiming a status that allowed them to pay even fewer taxes.

The ploy let the company to reduce the overall size of its payroll, allowing it to pay less in payroll taxes, Medicare, and related expenses.

Two hours after the verdict, Trump issued a statement titled, “MANHATTAN WITCH HUNT!” In it, he reiterated the same arguments that failed to convince the jury: claiming that the company’s CFO acted on his own and misquoting his testimony, which in reality revealed that the company benefited from the fraud as well.“Disappointed with the verdict in Manhattan, but will appeal,” Trump’s statement said. “New York City is a hard place to be ‘Trump.’”

The Manhattan District Attorney’s Office spent roughly six weeks at trial against the Trump Corporation and Trump Payroll Corporation—sister companies within the real estate mogul’s corporate umbrella. The time was stretched out by holidays, the incessant police sirens that echoed in the streets below, and a COVID outbreak that sickened a witness and even the judge.

Prosecutors made the case that top decision makers were all in on the plot to routinely reduce executives’ official salaries in various ways to avoid paying taxes. For prosecutors, the primary challenge came from proving that these executives did it to enrich themselves—and helped the business in the process.

Joshua Steinglass, an assistant district attorney, put it simply to jurors in his closing arguments last week Friday. He described how an employee seeking to buy a $25,000 car would have to ask for a raise worth double that to account for taxes. But the employee and company both make out like bandits—avoiding a heap of taxes—if the company just gives the employee a $25,000 car and reduces their pay by the same amount.

“By far the most significant benefit… is that it allowed these companies to pay these executives less than they otherwise would have,” Steinglass told jurors.

Despite damning spreadsheets, self-implicating memos, and checks signed by Trump himself, it all came down to three words: “in behalf of.”

The company’s defense lawyers remained fixated on a murky legal definition of that phrase, trying to raise the bar necessary to tie executives’ misdeeds to corporate fault. While they acknowledged Weisselberg and McConney schemed to play accounting games, they argued that the pair were not acting “in behalf of” the company, as the state law requires.

On Monday, Justice Juan Merchan guided jurors on how this has "a special meaning."

"It is not necessary that the criminal acts actually benefit the corporation. But an agent's acts are not 'in behalf of' the corporation if they were undertaken solely to advance the agent's own interests. Put another way, if the agent's acts were taken merely for personal gain, they were not 'in behalf of' the corporation," he said.

In other words: Did Weisselberg and McConney help out the company by cheating?

Jurors thought so.

Tuesday morning, Trump took to his own social media site to whine about the trial.

“Murder and Violent Crime is at an all time high in NYC, and the D.A.’s office has spent almost all of its time & money fighting a political Witch Hunt for D.C. against “Trump” over Fringe Benefits, something that in the history of our Country, has never been so tried in Court before,” he wrote.

The biggest revelation from the trial—and the one that most undercut the company’s portrayal of Weisselberg as a lone betrayer of the Trumps—was that while the company had publicly cut ties with Weisselberg it had secretly been paying him a full-time salary and kept him on in an advisory role.

“Allen Weisselberg didn't steal from the company. He stole with the company. The Trump Corporation isn’t the victim in this,” Steinglass told jurors last week.

“You know what the most unusual thing in this case is? The same day he finalized the terms of the plea, he had a birthday party in Trump Tower! Maybe if he hadn’t agreed to testify against the Trump Organization, it would have been a bigger cake,” he added, as some jurors smiled and held back laughter.

From afar, Trump himself denounced the trial on social media as an unfair political prosecution. The judge tried to avoid a political clown show by weeding out jurors who displayed any outright bias against the former president who tried to take down American democracy. But it ended up being Trump’s own corporate defense lawyers who dragged politics into the courtroom, repeatedly telling jurors that the former president and company CEO knew nothing of the accounting shenanigans going on at his own company. They made the assertion so many times that the judge later commented how he “thought it was a surprise the extent to which the defense brought up Mr. Trump’s name.”

In the trial’s final moments, prosecutors drove right through the door Trump’s defense lawyers had opened. They once again showed jurors a damning memo where Trump himself signed off on a memo in which the COO directed the controller, McConney to reduce his salary by $72,000 to pay for the tax-free rent.

“Mr. Trump explicitly sanctioned tax fraud, that's what this document shows!" Steinglass bellowed.

Yet he clarified, "Donald Trump is not on trial. We don't have to prove a thing about what he knew or what he didn't know.”

But that might come later. On Monday, The New York Times reported that Manhattan DA Alvin Bragg has recruited a federal prosecutor with experience nailing Trump to revive the office’s criminal investigation of the former president, which had previously collapsed.

And it’s still unclear how much prosecutors have explored statements Trump made under oath last year, when he admitted that he personally oversaw Calamari’s pay and untaxed benefits.

This trial is not to be confused with the half dozen other legal challenges currently targeting the former president. Trump is facing a quickly developing Department of Justice criminal investigation into the way he tried to cling to power in 2020 by lying to the American public about supposed voting fraud and inciting an attack on Congress, plus a probe into the way he kept classified documents at his Palm Beach mansion-club. He’s also the target of a local Georgia criminal investigation into his attempts to intimidate an elections official there into flipping that election’s results.

This trial is also separate from the civil case brought on by the New York Attorney General, who is trying to shut down the company and seize its assets over the way it regularly lied about its real estate portfolio—making up non-existent building space and inflating values to obtain better bank loans or maximize tax-write offs on donated land.