A restaurant menu is the nexus of a diner, a dinner, a chef and the suitably hospitable environment in which a meal is served. It wasn’t always this way.

Until the rise of the modern restaurant in ancien régime France, a traveler’s gustatory experience was characterized by near universal mediocrity–or worse. Marco Polo, describing his crossing the Gobi desert on the way east to see the Chinese Emperor in the 13th century, wrote in his Travels, “It consists entirely of mountains and sands and valleys. There is nothing at all to eat.”

In the intervening centuries, for those on the road fortunate enough to find a meal at an inn, a neighborhood tavern, a boarding house or by the fireside of a toll-house keeper’s home, such weary travelers chronicled their frustrations. Diners’ complaints were legion: There was typically just one fixed time for eating, woe to those who missed the dinner gong; no choice of dishes; and a chaotic service where every diner lunged and wolfed down what he could when dishes hit the table. Adding insult to injury, what was served was often spoiled and enforced seating often landed an innocent diner next to pickpockets, criminals or unprincipled gluttons at the so-called ‘communal’ table. (It was well into the 19th century before the fairer sex was even welcome in so-called fine dining establishments!)

Not until the late eighteenth century in Paris, when the first rich aromas of true hospitality wafted from simple soup shops, would hungry eaters encounter a new marvel: A public place offering a selection of tasty broths; where patrons were welcomed with a table of one’s own; and with each dish served up by waiters in a cozy setting. A client could patronize any time, day or night, and choose a novel entrée from a detailed menu that listed all the latest fashionable dishes.

In fact, as food historian Steven Heller ably recounts in the introduction to Menu Design in America – 1850-1985, in its original pre-revolutionary French incarnation a restaurant was a meat- or vegetable-based broth, a healthful restorative. Thought to be especially nourishing by growing numbers of affluent, health-conscious Parisians, such concoctions were served at privileged addresses in the three decades or so before the 1789 revolution that turned the world upside down.

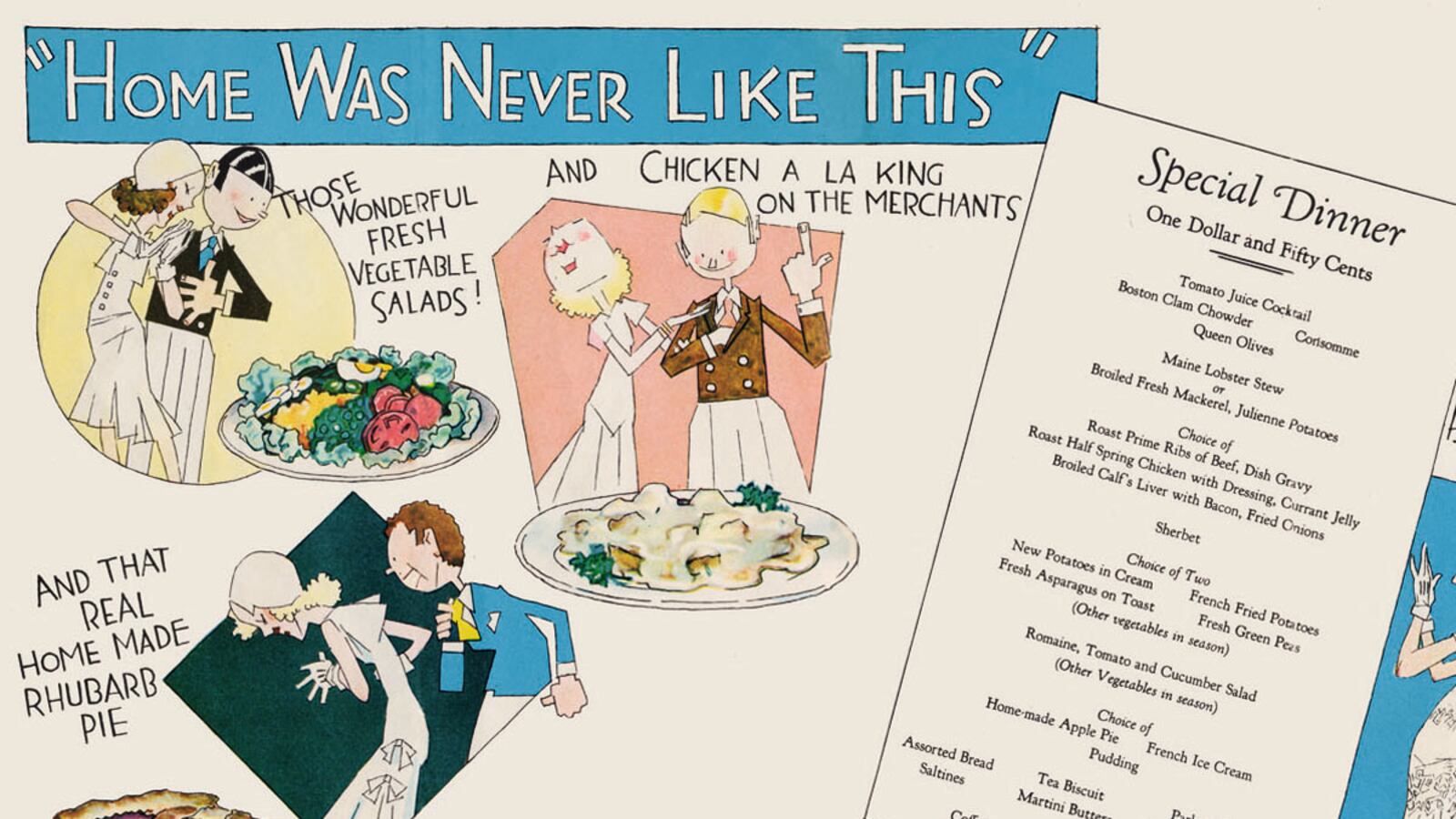

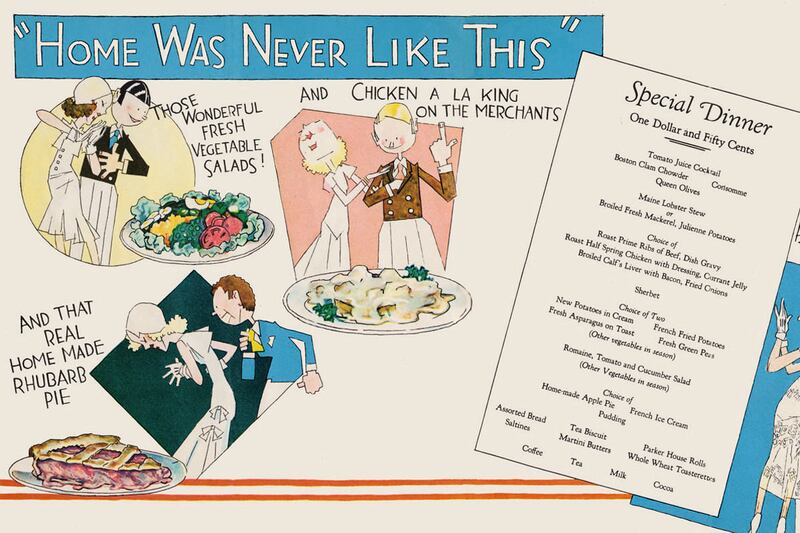

It was at these establishments that a list of restaurants launched the restaurant as we know it today, and with it, the menu, as the book’s editor and cultural anthropologist Jim Heimann explains. As the list of broths, soups and liquid restoratives expanded in variety and price, these bills of fare–with items listed one by one on a chalkboard (the menu term, á la carte literally means “on the card”)–evolved rapidly. Menus became more detailed with their descriptions. Colorful tints, eye-catching graphics and mouth-watering images combined and voila, the menu was born!

Menu Design in America - 1850-1985By Jim Heimann [Ed.], Steven Heller, John Mariani392 pagesTaschen, 2011$59.99

From antebellum watering holes and gilded age hotels to late 20th century gastronomic hot spots, one after another menu explodes like a colorful series of Fourth of July fireworks in the pages of Menu Design in America – 1850-1985. In the book’s almost 400 large-format pages, more than 800 historic menus are featured, with many coming from the personal collection of Heimann. Detailed captions accompany most of the menus and are handled succinctly by food historian and restaurant critic John Mariani.

All these pre-revolutionary developments in France’s infant restaurant trade were given a huge boost after 1789. In the aftermath of The Terror and beheadings, a host of talented chefs formerly employed by aristocratic families found themselves out of work. Not surprisingly, a large number of these chefs, along with the original core of Parisian soup-makers and growing ranks of enterprising caterers transformed themselves into restaurateurs.

A number of these old-world cooks and bottle-washers flocked to America, where they soon established a gastronomic beach head in New York. A host of foreign-trained chefs quickly opened luxurious restaurants and printed elaborate menus; in the process, these outposts of civility and taste transformed our culinary landscape. As the editors of Menu Design in America emphasize, until their arrival, our colonial-era dining choices chiefly consisted of oyster shacks, chop houses, whiskey joints, and beer halls.

After a few short decades, these foreign-born chefs and restaurateurs, like the Delmonico brothers of the early 1800s, opened our eyes and palates to creamy bisques, sautéed fricassees, truffled sweetbreads, fine wines, vintage Champagnes and exotic liqueurs, and all matter of delicate pastries and confected sweets. Thanks to these pioneering restaurateurs and the menus they created for our pleasure, America’s dining scene is immeasurably richer.