MEXICO — The lives of dozens of Mexican families were forever altered when bullets rained down on their sons, rural college students who dreamed of one day becoming teachers.

Two years ago this Monday, a convoy of corrupt police ambushed students traveling to the city of Iguala, from the underfunded, all-male Raul Isidro Burgos Rural Normal School in the impoverished state of Guerrero. The hours-long encounter, often referred to as “the night of terror,” left six people dead—both students and passersby.

But what happened in Iguala that night was just the beginning of a case that continues to shake the country.

As morning came on September 27, 2014, the country awoke to a horror that has not yet ended—a tragedy known simply as Ayotzinapa, after the tiny town where the teaching school was built.

That morning, as blood dried in the streets of Iguala, and bodies were collected, dozens of students who were unable to escape remained unaccounted for. Mexico soon learned that 43 students had been forcefully disappeared, taken by corrupt cops in the night. Now, 24 months later, the fate of most of them remains unknown.

The government’s official theory is that the 43 young men were taken by police and delivered into the hands of the local Guerreros Unidos drug gang, who systematically murdered, and then mass-incinerated them in a garbage dump in nearby Cocula, in the troubled state of Guerrero—Mexico’s most violent now for three years in a row. Then-Attorney General Jesús Murillo Karam, who resigned after scathing criticism of the maladroit investigation that ensued, called this version the “historic truth.” But there is seemingly little truth to it.

Though this wouldn’t be Mexico’s first massacre since the start of the drug war—which has killed more than 100,000 and left at least 27,000 officially missing—or even since President Enrique Peña Nieto took office in late 2012, the forced disappearance and probable mass-murder of “the missing 43” has become the most emblematic case against the Mexican government in recent memory.

To many it is evidence of a failed “narco-state” of unchecked cartel violence and official complicity.

“We’re going to kill you all,” the police told the students that night, according to testimony from one of the surviving bus drivers. Yet the students’ families continue to pray for and demand their sons’ safe return.

“You took them alive, and we want them back alive,” the parents tell the government. It has become their mantra.

Their sons, who traveled aboard a small fleet of buses they had commandeered—a practice that has become common among normalistas, and is usually tolerated—were making plans to attend the upcoming march in Mexico City on October 2, in memory of the students who died in the 1968 Tlatelolco student massacre.

But in Mexico history has a way of repeating itself, and they, of course, never made it. Now, Mexico commemorates their loss.

The order to attack the boys came from high up in the city’s hierarchy, from Iguala Mayor Jose Luis Abarca and his wife Maria de los Angeles Pineda, who later was revealed to be a key player in the Guerreros Unidos drug gang, with family ties to the Beltrán Leyva cartel.

The political power couple first claimed no knowledge of the attack—“I was dancing,” said the mayor after the chaos—but after repeatedly denying their role, the couple made a run for it, spending weeks on the lam, before their November 2014 arrest in a shabby Mexico City home. Since the investigation began, the fugitive mayor and his wife, along with more than 100 others—mostly police officers, and small-town criminals—have been arrested and interrogated for their alleged roles in the disappearance. Yet, still, the students have not been found.

“We’re just another missing persons case,” said survivor Omar García. “In Mexico and in Guerrero they kill people and say it’s collateral damage of their fucking politics—the [fighting] against different forces and even amongst themselves. We don’t want any part of it. We want a Mexico that’s just, and free.”

That night García rushed to the scene of the attack to try to save his fellow students. He came across the badly injured body of one, and helped carry him to safety. Nineteen-year-old Aldo Gutierrez had taken a bullet to the head, but thanks to his fellow normalistas he did not die. Gutierrez has spent two years in hospitals, in a vegetative state, since that bullet destroyed 65 percent of his brain.

Edgar Andrés Vargas also stepped in to rescue his friends that night, but instead wound up shot in the face. He has had multiple facial reconstruction surgeries to rebuild the parts of his nose and mouth that were destroyed, but unlike dozens of his classmates he is alive and free. Two months ago, Vargas graduated as a teacher from the Ayotzinapa rural school. He wore a blue surgical mask to cover his face.

But many of Ayotzinapa’s students will never fulfill their dreams of becoming teachers. Julio Cesar Mondragon, a young father, was tortured to death that night. He had 40 broken bones, and when his body was found, his face was missing.

Although that night directly affected hundreds of lives, the number 43 has become a symbol in Mexico, a badge that’s emblematic of the violence that has plagued the country as a consequence of the failed drug war, which continues to amass casualties with seemingly no end in sight.

Of the 43 missing students, only one, Alexander Mora, has been confirmed dead, after an Austrian forensic lab analyzed what authorities claim are the students’ remains—garbage bags filled with ash and a few charred bone fragments, which were discovered in a river along the edge of the Cocula dump. One other student is believed to have been positively identified, but the remaining students’ fates continue to be cause for speculation.

The Mexican government has made every effort over the past two years to “close the case,” but have offered the families a story that has been refuted by everyone but the government, a fiction that falls apart upon even the least discerning examination.

Twenty-four months since their disappearance, since the students were picked up by police in Iguala, and delivered into the hands of organized criminals, still no one really knows what happened to them. Were they systematically killed in a garbage dump in the neighboring town of Cocula, before being mass-incinerated on site, on a pyre made of wood, trash, and burning tires, as the government insists? Independent experts resoundingly say “no.”

José Torero, a Peruvian fire safety engineer from Australia’s University of Queensland has been sceptical of the official version since visiting the site in 2015 and finding no evidence to corroborate the government’s tale.

He decided to attempt to duplicate the alleged incineration using wood pyres and pig carcasses, and found that it would take more than 60,000 pounds of wood to successfully disappear the corpses in the setting described by authorities, and that it would be “scientifically impossible” to do so without the ash being contaminated by organic material, which the bags allegedly containing the students’ remains did not contain.

His theory is that the only way these bags of ashes could have been produced is by controlled cremation. Forensic evidence, and satellite imagery of the site have also failed to corroborate the government’s findings, which are based on dozens of confessions—many of which are the result of torture.

“We’re poor, but we’re not stupid,” said a mother of one of the victims after Torero first announced his findings, criticizing the government’s claims. The parents of the missing call the official version an “historic lie.”

“We know that they are alive, and that we have to find them,” the parents’ spokesman Felipe de la Cruz insists. They have held out hope, even as the rest of the country has steadily begun to give up.

Emilio Álvarez Icaza, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights’s executive secretary who first sought out the help of external fire expert Torero, ended his term last month, after nearly two grueling years following the case. He did not mix words this week, when he called Ayotzinapa a “state crime” and reiterated the government’s responsibility to investigate the role the Mexican army may have played in the students’ death.

“This administration protects, hides, and covers for the military,” Icaza said, adding fuel to a long-standing theory that the 27th Infantry Battalion Base in Iguala may have played a role. Early last year, several parents and students were injured after hijacking a Coca-Cola delivery truck, and ramming it into the infantry building, one of many protests that have taken place at the site.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights appointed a group of experts from various fields to conduct an independent investigation in conjunction with the Mexican government early on in the search. The Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts repeatedly complained that their attempts to interview members of the military had been blocked. They too insist that what the government proposes took place at the Cocula dump is “scientifically impossible,” and earlier this year the experts released their final report on Ayotzinapa, before packing their bags and heading home.

Parents pleaded with them to stay, chanting “Do not leave us! Do not leave us!”

But the experts had to go, leaving in their wake a damning 608-page report concluding that the Mexican government sabotaged its own investigation. They volunteered a series of recommendations for the Mexican government—common-sense suggestions, like don’t contaminate evidence and crime scenes, and do not torture your suspects into confession.

Now, the recommendations the experts made continue to prove their worth. The case against the alleged leader of the Guerreros Unidos drug gang, Sidronio Casarrubias Salgado, who was arrested in October 2014, for example, is falling apart. Earlier this month, a judge ruled in his favor, agreeing that his human rights have been violated—which means that, like others arrested for their alleged roles, he was tortured.

Cases like his further jeopardize the hope that there will be justice for the students and their families. Of 130 people who are behind bars today in relation to this case, none have reached a definitive court resolution, and dozens of suspects’ cases are being investigated as possible cases of torture.

“The Mexican government seeks to hide the involvement of high-level authorities in this crime at all costs, but their ‘historic truth’ is no longer even a possibility,” said Daniella Burgi-Palomino, a senior associate at the Latin America Working Group, after the final report was published. “The Experts’ new report is definitive; there are no arguments that allow the government’s version to stand anymore.”

“The Ayotzinapa tragedy has exposed how President Peña Nieto’s administration will stop at nothing to cover up human-rights violations taking place under their watch in Mexico,” said Erika Guevara-Rosas, Americas Director at Amnesty International, this week.

For everyone who has followed this case closely over the past two years, it is difficult to not find the outcome of the investigation disheartening. Journalists I’ve spoken to in Mexico, who like myself have watched this story take twists and turns as it has unfolded over the years, speak frankly about the impact it has had on their work, and their ideas about Mexico’s ability to lift itself out of the criminal mess it’s embroiled in.

Andalusia Knoll, a journalist who has followed this story since day one, traveling across Mexico with the families of the missing students, spoke to me about the impact this tragedy has had on her.

“It’s hard to spend so much time with families who are grieving and have suffered something so tragic as the disappearance of their sons, facing two years without information on their whereabouts, and subject to what is essentially government torture—they’ve been feeding them lies, and throwing them through loops for 24 months—without taking some sort of side,” Knoll said. “It’s reaching a point where you realize that objectivity is not the goal of our work as journalists, but rather honesty.”

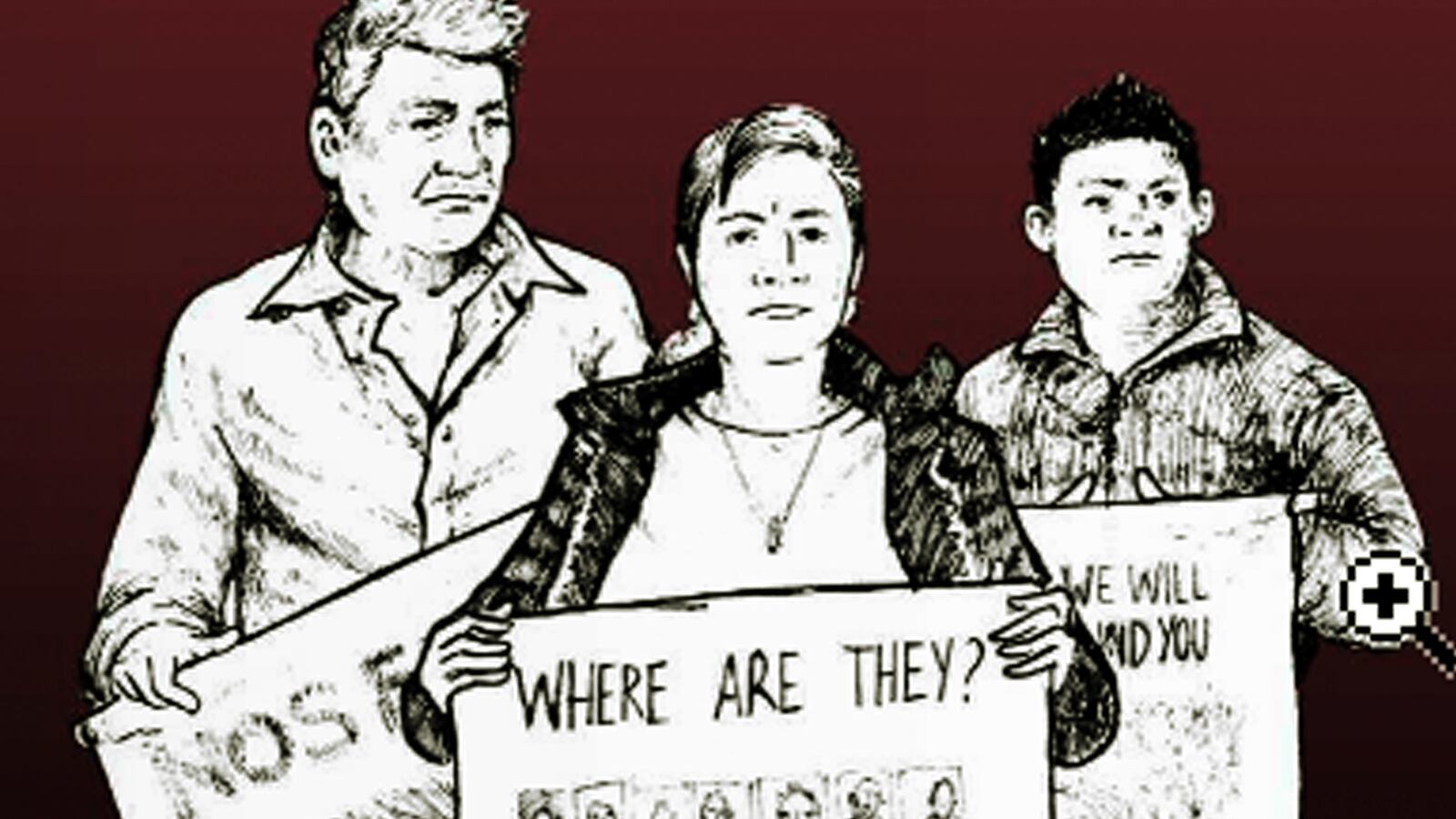

Knoll has taken an activist’s role in the case, and this Thursday published part one of a graphic novel that tells the story of what happened in Ayotzinapa from the perspective of survivors, families, and journalists who have lived through it. Alive You Took Them is a collaboration between herself, illustrator Xavier Corro, graphic designers, journalists, fact-checkers, human-rights observers, and the families of the missing 43.

She spoke to me about her work with the families affected by this unresolved case who “just want to know the truth about what happened to their sons—a truth that the government has not offered.” The families have stood firm about no longer meeting with the government because they don’t believe they’ve tried or made any progress on the investigation, and have also “failed to sanction those who are responsible for the false version of events.”

“The fact that unarmed students from a poor rural area who were just trying to get ahead in life and get an education were so violently attacked really resonated with people,” Knoll said, looking back on two years without justice. “Mexico is a country where education is something you have to fight for, and many never have access, nor the opportunity to become educated. These young men were looking to make a better life for themselves and their families and instead became a symbol for Mexico’s failures. This is a state crime that the government cannot cover up, which doesn’t mean they aren’t still trying to.”

The parents have put their lives on hold to keep their sons’ memories alive. “These families are poor, undereducated people whose sons were their hope for a brighter future. They are the ones who continue to fight, continue to refuse the government’s fiction. Normally these levels of violence cause people to retreat into their homes, and become frightened of speaking out. But these families are a dignified example of people struggling not just for the return of their sons, but also a more peaceful Mexico, a Mexico where they—the poor, undereducated, rural, indigenous people—also count.”

“These people matter,” Knoll insisted—her voice cracking. “They refuse to let their sons be just another line in the newspaper.”

The parents of the missing 43 initially benefitted from nationwide support, and people across the country mobilized in support of the students, in fiery protests, which threatened to destabilize the government. But that support, following the government repression of the massive protests that resulted across the country, has begun to die down as the country has grown exhausted with their fight, and distracted by subsequent massacres, like the 2015 Apatzingán and Ocotlan massacres, in which federal authorities extrajudicially executed dozens of people in Michoacan and Jalisco.

Last year, former President Vicente Fox went so far as to essentially tell the families to just get over it. “They need to accept reality," Fox said. "The country has to keep advancing. And they do, too."

But for the students’ families, the fight is far from over.

Despite the arrests, despite the many officials who have lost their jobs—including chief criminal investigator Tomas Zeron, who relinquished his post two weeks ago in anticipation of the two-year anniversary—despite the controversy this case has brought the Mexican government and President Peña Nieto, and two years of searching, the truth remains elusive.

The parents have nowhere to pray for their sons, no tomb to take flowers to on Day of the Dead, and no way to give up hope and accept that their children will not come home. The missing students exist in a limbo, somewhere between alive and dead. But this case, which has exhausted the country, and claimed many political casualties, is unlikely to ever be solved.

“Ayotzinapa no se olvida,” thousands across Mexico say today.

“Ayotzinapa will not be forgotten.”