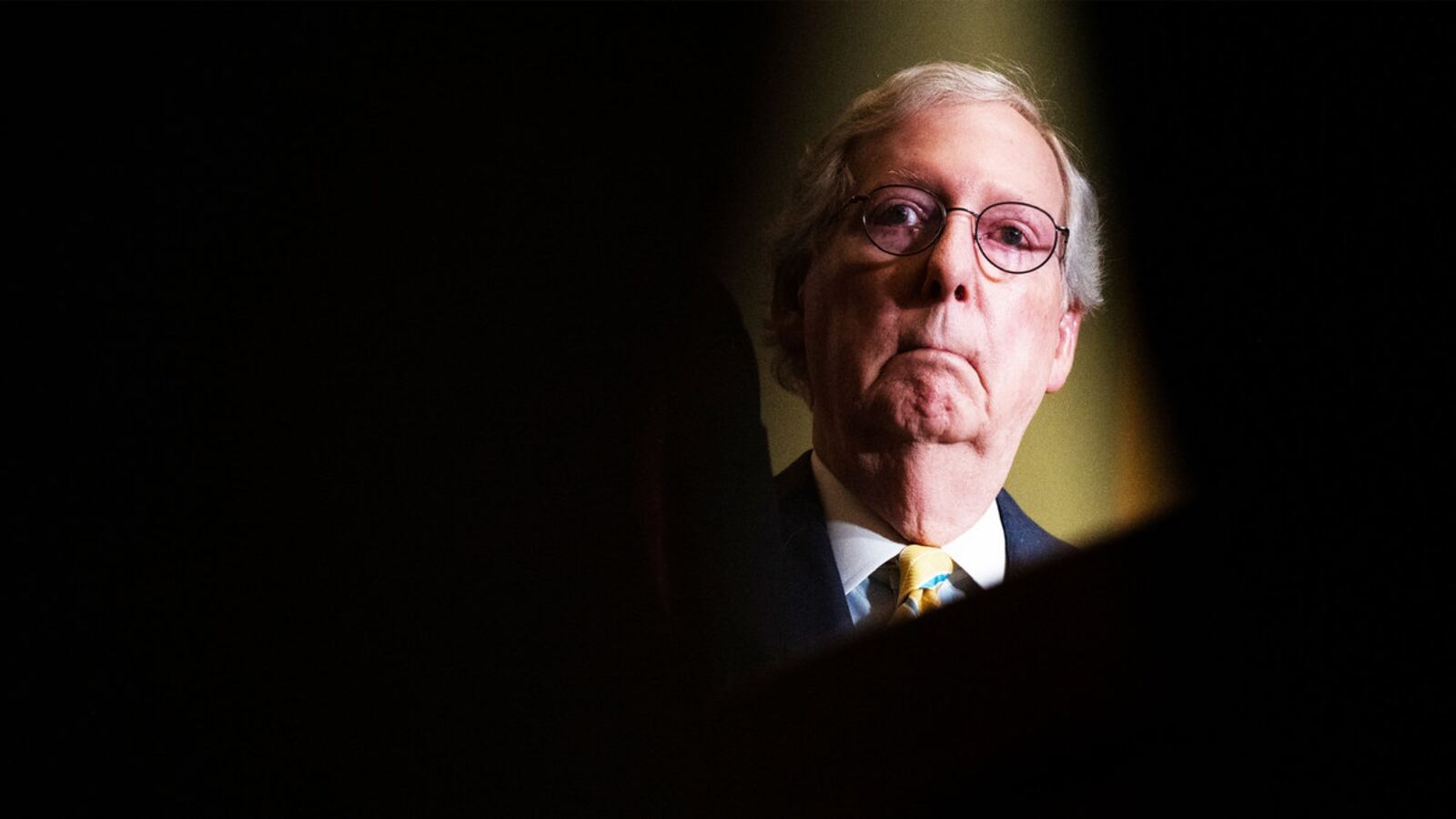

The mass murder of 19 children and two of their teachers in Texas last week prompted Senator Minority Leader Mitch McConnell to say he’s hopeful Senators can find “a bipartisan solution” to the problem. But if that sort of response sounds familiar—and not particularly inspiring—that’s because he’s said it before, only to close the door later.

McConnell told CNN that he “encouraged” Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX) to engage with Democrats Sens. Chris Murphy (CT) and Sen. Krysten Sinema (AZ) about potential areas of agreement on new gun laws.

"I am hopeful that we could come up with a bipartisan solution," he said.

While it is notable that McConnell signaled his willingness to talk about changes to laws that regulate gun ownership in the United States, in McConnell’s case, it’s only a small step above immediately dismissing action on guns.

Time and again, McConnell’s “hope” for a bipartisan solution has simply prolonged the inevitable: inaction.

In June 2016, after a man with a gun murdered 49 people at the Pulse Night Club in Orlando, McConnell told reporters “nobody wants terrorists to have firearms."

"We’re open to serious suggestions from the experts as to what we might be able to do to be helpful," he said.

But when a bill that would have given the Department of Justice the ability to “deny the transfer of firearms or the issuance of firearms and explosives licenses to known or suspected dangerous terrorists” was put for a vote, it failed along party lines with the exception of one vote. McConnell was one of the 53 Republican senators who voted no.

In August 2019, after mass shootings within 24 hours at a Walmart in El Paso and a nightclub in Dayton, then-President Donald Trump expressed support for “really common-sense, sensible, important background checks.”

“Today, the president called on Congress to work in a bipartisan, bicameral way to address the recent mass murders which have shaken our nation,” McConnell said in a statement on Aug. 5. “Senate Republicans are prepared to do our part.”

“Only serious, bipartisan, bicameral efforts will enable us to continue this important work and produce further legislation that can pass the Senate, pass the House, and earn the president’s signature,” he said. “Partisan theatrics and campaign-trail rhetoric will only take us farther away from the progress all Americans deserve.”

“What we can’t do is fail to pass something,” McConnell said during an interview on WHAS radio a few days later. “The urgency of this is not lost on any of us.”

Even Trump bought into McConnell’s words.

“I am convinced that Mitch wants to do something,” Trump told reporters on Aug. 13, 2019.

But a month later, as Trump’s passion for the issue faded, McConnell changed course.

“My members know the very simple fact that to make a law you have to have a presidential signature,” he told reporters on Sept. 10.

No vote was ever taken.

McConnell’s office declined to comment for this report.

McConnell’s habit of deferring to some theoretical, distant concept of a bipartisan solution has the same effect as politicians offering their “thoughts and prayers” to victims—only it’s less recognizable as an empty gesture of change. McConnell, however, hasn’t always been above offering those thoughts and prayers.

In June 2015, after a white supremacist shot and killed nine people at a church in Charleston, South Carolina, McConnell took to the Senate floor to let “the American people to know the Senate is thinking of them today and the victims that they loved.”

“We’re also thinking of the entire congregation at this historic church,” he said.

No legislative change ever came from the Charleston shooting.

The same can be said of the mass shootings later in 2015 at the Umpqua Community College in Oregon that killed 10 and the San Bernardino shooting that killed 16. McConnell was sympathetic for the victims and their families, but he was quick to criticize President Barack Obama’s proposed solutions in early 2016 as partisan.

“In the wake of the President’s vow to ‘politicize’ shootings, it’s hard to see today’s announcement as being about more than politics,” McConnell said.

In the days after the Las Vegas shooting, when 59 people were killed at a concert, McConnell told reporters it was “inappropriate to politicize an event like this.”

“The investigation has not even been completed, and I think it’s premature to be discussing legislative solutions if there are any,” he said.

Still, after 17 people at a high school were murdered in Parkland, Florida, McConnell was instrumental in passing one piece of reform legislation: the so-called Fix NICS Act, which helped ensure criminal record information was entered into the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) by state and federal authorities. McConnell also oversaw the passage of a STOP School Violence Act, which provided funding to help prepare and prevent school gun violence.

But those reforms were far from the sweeping changes that most advocates believe are necessary to actually reduce gun violence. And more often than not, McConnell’s willingness to engage on issues that might regulate or augment current firearms laws has been fleeting.

Of course, McConnell doesn’t always just defer to a bipartisan solution that doesn’t exist.

After the shocking Sandy Hook shooting in 2012, McConnell told reporters days later that the entire Congress was “united in condemning the violence in Newtown and on the need to enforce our laws. As we continue to learn the facts, Congress will examine whether there is an appropriate and constitutional response that would better protect our citizens."

But by January, in an interview on ABC, McConnell made it clear his focus was elsewhere when asked by host George Stephanopoulos about whether Republicans would be open to suggestions by a new task force on gun violence headed by then-Vice President Joe Biden.

“Well, first, we need to concentrate on Joe Biden’s group, and what are they going to recommend?,” McConnell said. “And after they do that, we’ll decide what, if anything, is appropriate to do in this area.”

“But the biggest problem we have at the moment is spending and debt,” he continued. “That’s going to dominate the Congress between now and the end of March. None of these issues, I think, will have the kind of priority that spending and debt are going to have over the next two or three months.”