In 1999, I was a junior in high school, and a big story in the small town of Barre, Vermont, as a suspected school shooter.

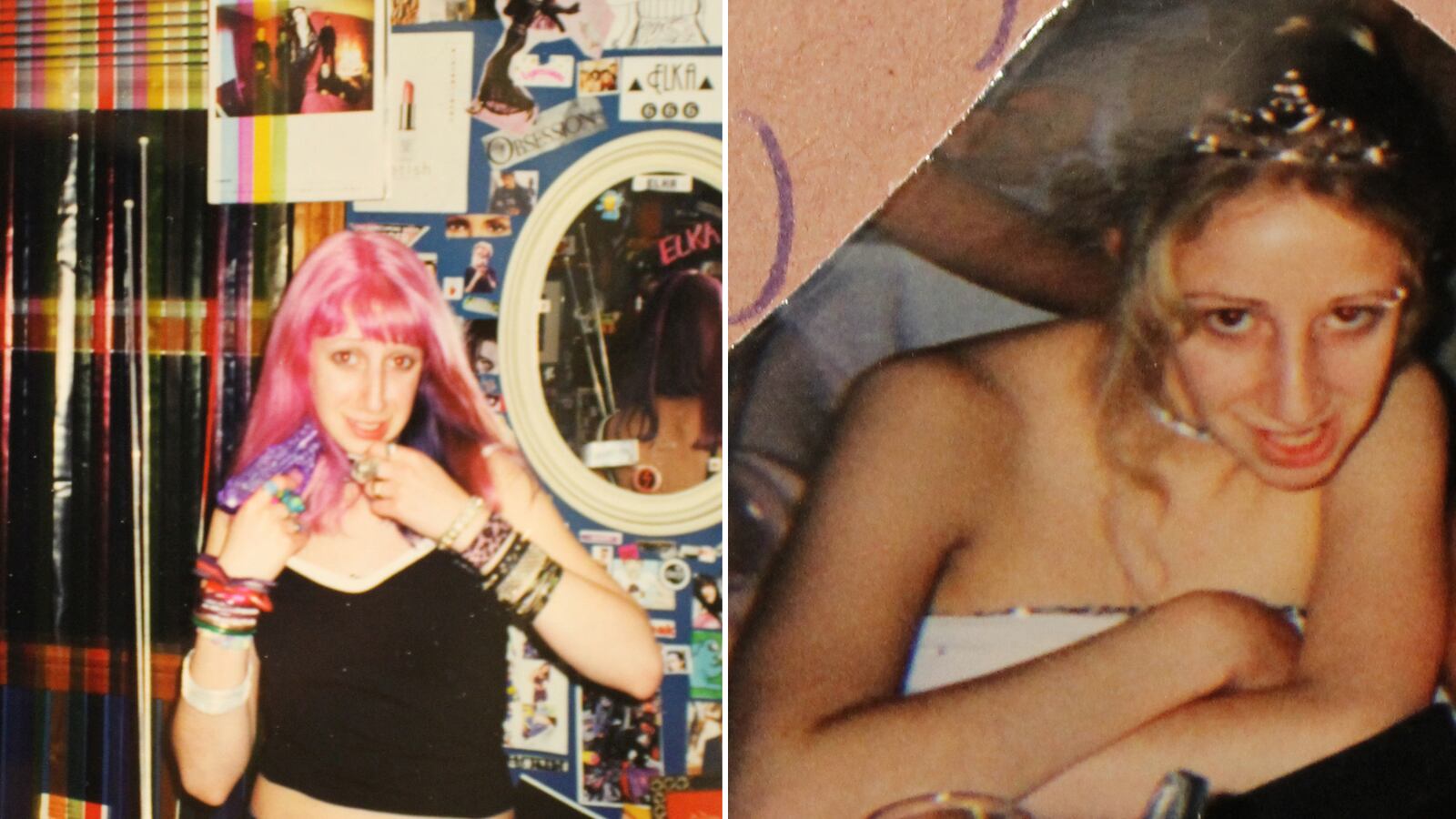

It was at once a dreary and a weird town, but I felt, maybe I was, too weird for it. After jockeying for position with the other on-the-outs tweens, and enduring bullying from friends, classmates, and even teachers, I started dressing truly weird and mostly keeping my own company. I also kept a jokey rhyming book, which I’d shared with some friends at the time and which included cheerful descriptions of murder by disco ball at the Elk’s Club of kids who I’d felt had been nasty to me, giving them surreal fake names. Later, I assisted in leaving a nasty note on the windshield of a car that belonged to a girl who’d spread cruel rumors about me with the usual high-school stuff: that my one friend and I were lesbian lovers, but we fucked lots of guys, too.

The note, left days after Columbine, led to the police investigating me and then finding out about my journal, and that in turn led to a wave of local headlines about the girl with the “prom-killing manual.” I was feared and completely cast out, and banned from my junior prom, which was held at the Elks Club (pretty much every event in town was there). I got blacklisted from classes, physically assaulted, and finally I started to revel in my notoriety, and to identify with real school shooters and embrace feeling close to what everyone already feared me to be.

Like with so many “weird kids,” I left most of my nasty cycle behind when I left Barre to go to college. Some of my teen feelings resurfaced while watching the Sandy Hook coverage. As a reaction, I wrote an essay for Vice about my experience because I felt like there was an overwhelming void in the discussions about school violence. There didn’t seem to be any room in all the noise for the voices of those deemed troubled, and so I wrote about my painful youth in hopes of reaching people going through a similar situation now.

After my essay ran, a lot of old classmates picked up on it and they helped spread the article around the Internet like wildfire in much the same manner, I couldn’t help but notice, that they had spread negative gossip about me back in the ’90s. I found this shift surreal, and quite touching. My hometown newspaper even ran a story about my story, on the Sunday front page, a positive one: “Former SHS Misfit: ‘Threat’ Spun Out of Control.”

I also heard from a number of those classmates, with almost all of the messages I received from them beginning with an apology, though they didn’t come from my old tormenters but from students I remembered as bystanders. What stood out from their notes was that each person, regardless of how I had perceived their social standing, related to my essay not as a perpetrator of harassment but as a victim. My experience revived their own recollections of being bullied.

The notes didn't change how I feel about the past, but they did put things into perspective. I was never very angry at my classmates—even at the time I was more upset with the teachers and other adults who let them behave this way. A lot of kids had very bad home lives, and several of the girls I was friends with at one point or another had been sexually abused as children. I really had to remember these factors and let that anger go because if not I just couldn't go on with life in a healthy manner. I guess it helps me to put it even more in the past and even further realize that they too were going through their own confusions and that many of them were too scared to do "the right thing." I think most of them followed the poor examples that they had to follow in school and at home, and didn’t have a strong role model or a voice of reason to listen to.

But the notes did affirm something about how bullying distorts everyone involved in it—the bullies, the bullied, and the bystanders as well. Even those who I felt were popular, when they look back at high school don't see themselves that way; they see when they felt bad about themselves and when they were mistreated. That works at all social levels, and those are experiences that stick.

A lot of the people who wrote had already apologized, years before I published my article. Others, I was already friendly with, in high school or later. One example is Robbie (not his real name). He attended high school with me and was part of the popular crowd. After my article was published, Robbie wrote to tell me that he was a lot like me when he was in junior high, and in fact had come to Barre to escape his bullies. This is what he told me:

I suffered routine verbal and physical abuse by many of the other kids—strangely, they were often the type of kids who came from a “nice family,” or a “great community”; the kind of kids most people would be proud to parent, and so on.

There was this one time, I had just finished lunch and was leaving the cafeteria; I was by myself of course, with headphones in my ears, filing out into the hall with all the other students. Within minutes my feet were kicked out from beneath me. I of course fell to the floor. And as if that wasn’t amusing enough for the guy who did this to me, he then bent down to my level, grabbed my neck, and shoved my head between my legs. Forcing me to pantomime fellatio on myself. All the while kicking me and referring to me as a “dick-sucking faggot.” No one bothered to stop him, let alone tell him to stop. Rather, breaths all around me were wasted on rounds of hushed laughs and snickering. No one was there to tell this person that what he was doing was wrong, that what he said was wrong. And this is only one of many incidents of a similar caliber.

Although he was popular, I had viewed Robbie as a neutral player, one who never targeted me specifically. And I had no sense then, or occasionally thinking back on those years later, of his inner conflict. He explained to me how strange it was when he infiltrated the in-crowd:

It was very interesting to go from being the center of cruel behavior, to then, shortly after moving to Barre, finding myself running with a crowd that was often the epitome of those who previously tormented me. You can only imagine the perspectival shifting that occurred. (I sorta felt like Drew Barrymore in Never Been Kissed.) I suppose now, I wish I had spoken up more when I had the chance to then, to tell some of my friends to stop bullying and tormenting certain people. And if there were ever times when it may have seemed like I was guilty by association, that's probably because I was: my silence in exchange for acceptance nonetheless made me complicit on many occasions. There were a couple times when I did speak up, but it's funny how that just seemed to stoke the flames for some people.

I’ve felt that fire myself, when I bullied somebody “below” me in the scheme of things. In seventh grade, I put a girl through hell. She had thick glasses and was overweight. I called her “Hippo Girl,” and as I berated her I felt negative attention shift from me to her. It was a relief, using her as a temporary antidote to being a target myself. When she tried to stand up to me, I became irritated, and nastier. Maybe it was because I had already dictated her place. I didn’t like her challenging me; it was threatening. I feel that dehumanization is the only way one can successfully abuse another. There was no valid excuse for my behavior toward that girl, but it seemed natural, and it took a lot of effort for me to acknowledge, even years later, that what I did to her was horrible.

I believe that the majority of those who chose to apologize to me were, as Robbie said, guilty only by association. None of them owed me an apology—and neither do my old tormenters. They were kids, following a mob mentality. And the teachers helped lead, or at least allowed for, the mob.

In 2010, I attended my 10-year high-school reunion, where the theme was “Prom Do-Over.” When I walked into the doors of the Elks Club, the same establishment I was once “supposed to bomb,” an organizer of the event, Samantha (not her real name), made sure to inform others that I was “the real prom queen,” in terms of ballot count at my senior prom. I was allowed to go to my senior prom, and I did. That was during the time I embraced my bad reputation and I added fuel to the fire by telling people to vote for me, as I was aware that some were already voting for me as a joke. Samantha was one of my tormenters, and in high school her group seemed to take pleasure from putting me in my place.

At the reunion, Samantha told people, who then told me that “people are only nice to Gina now out of pity because her mom died.” My mother died when I was 20, and I couldn’t grasp the relevance. Genuinely curious, I reached out to Samantha after the event.

She eventually replied:

I honestly don't even remember a lot of details about prom, and I know nothing about comments about your dead mother. But I do know that people (not including myself) did vote for you to win prom queen as a joke, and then you ended up winning so I had them give the 2nd place winners [names omitted] the King and Queen spot. That's the truth.

This upset me. Nobody had ever told me I’d been voted prom queen, even as a nasty joke. And yet, a decade later she used that fact to hurt me, and it did. Perhaps we don’t so much rise above our traumas as simply walk away from them.

It’s interesting, too, because often once a place is dictated for you it’s hard for everyone, including yourself, to completely challenge and break through that designated role.