The season premiere of the CBS All Access drama The Good Fight imagines a world in which Trump was never elected, that all the badness of the last four years were merely a bad dream suffered by liberal Chicago lawyer Diane Lockhart, played by Christine Baranski. (This ties into the new Michelle Obama documentary, I swear. Just hang in there.)

Relieved to wake up in a present day in which Hillary Clinton is in charge and Donald Trump is nothing more than the head of a propaganda cable news channel, she recounts the litany of atrocities the nation endured in her “fictional” nightmare MAGA scenario. After she finishes, her bewildered colleague asks, “And where were the Obamas in all this?” In a brilliant, cutting deadpan, Lockhart announces, “They had an overall deal with Netflix.”

It’s true that the former president and first lady haven’t been the outwardly public—and outwardly angry—figures some expected, or wanted, them to be in the #resistance years following Trump’s 2016 election. That Netflix deal referenced—and scrutinized—in The Good Fight may be among their most visible public-facing contributions, developing and releasing sociopolitical documentaries like American Factory and Crip Camp under their Higher Ground production banner.

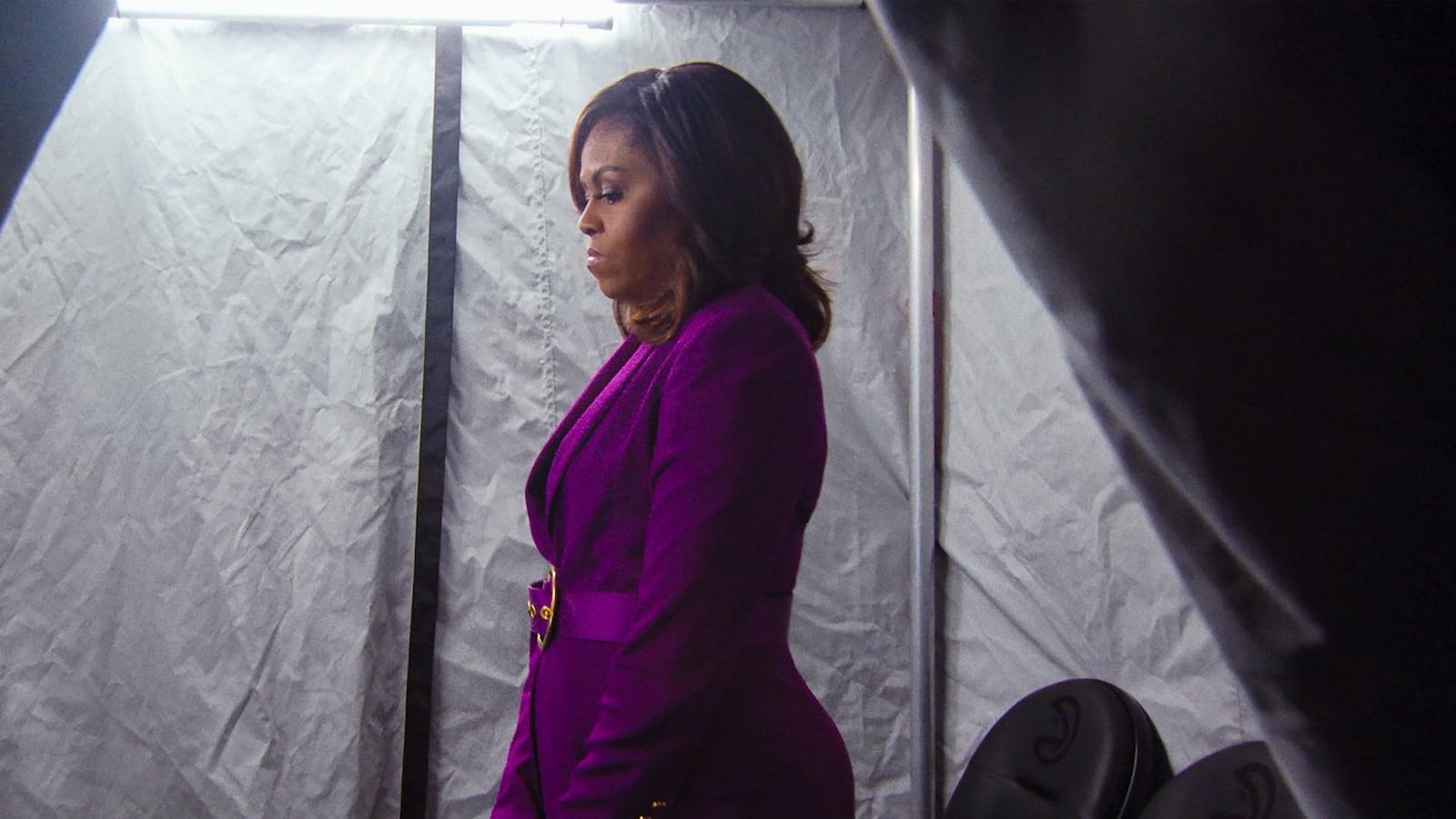

The release of Becoming this Wednesday, centering around Michelle Obama’s event book tour and conversation series in support of her bestselling memoir, should garner its fair amount of curious eyeballs, whether from those craving the nostalgic solace of 90 minutes spent back in the world of the Obamas or those parsing it for messaging or criticism of the Trump administration and the current powder-keg cultural climate.

Directed by Nadia Hallgren, Becoming offers some of that. But, more often, its interest is how Michelle Obama feels about those expectations of her.

While traveling the country and taking the temperature of how citizens, or at least her supporters, feel about things—“The energy out there is much better than what we see. I wish people didn’t feel badly because this country is good. People are good. People are decent.”—she grapples with her role going forward in guiding a way through it.

As the first black first lady, she considers how her experience in the White House and the expectations put on her then influenced the public role she chooses to live now. The crux of it all is that her life was taken from her for eight years, a service of which she was proud and is the greatest joy of her career. But now that her life is a semblance of her own again, what does she do with it?

“Every gesture you make, every blink of an eye is analyzed,” she said of her time in the White House. “You have the world watching every move you make. Your life isn’t yours anymore….The whole idea of doing the tour is about being able to have the time to actually reflect, to figure out what just happened to me? It’s the panic moment of this is totally me, unplugged, for the first time in a long time.”

In moments private and public, during staged interviews with the likes of Gayle King, Stephen Colbert, and Reese Witherspoon, she grapples with much of what we are all grappling with as a country: What is it that she wants to become?

The remarkable, and some might argue the disappointing, thing about Becoming is that the headlines are few and far between.

While Trump is casually referenced from the first minutes and the mood of the country scores the film’s entire conversation, it’s not until roughly two-thirds through the film that she addresses her negative feelings about his 2016 victory directly. Twice, she talks about how painful it is to her that black voters didn’t turn out to vote for Hillary Clinton, calling the decision not to vote more painful to her than those who voted for Trump.

“It takes some energy to go high, and we were exhausted from it. Because when you are the first black anything…” she said, referencing anecdotes from her Becoming book. “So the day I left the White House and I write about how painful it was to sit on that [inauguration] stage. A lot of our folks didn’t vote. It was almost like a slap in the face.”

“I understand the people who voted for Trump,” she continued. “The people who didn’t vote at all, the young people, the women, that’s when you think, man, people think this is a game. It wasn’t just in this election. Every midterm. Every time Barack didn’t get the Congress he needed, that was because our folks didn’t show up. After all that work, they just couldn’t be bothered to vote at all. That’s my trauma.”

It should be no surprise that Becoming isn’t a Trump-bashing attack ad, though some might have wanted that. Even though she's freed from the scripted proprieties of the White House and is now speaking more casually and freely than she ever did as first lady, it’s not exactly a part of Michelle Obama’s brand to do that.

Where Becoming reveals its value then is in the personal stories that uncover more about what life really was like those eight years for a black woman and mother plucked from obscurity to represent the most significant progress for African Americans in United States political history.

An early anecdote reveals what her last day in the White House was like, which was stressful for reasons you wouldn’t expect: her daughters Sasha and Malia wanted to have one last sleepover with their friends. She had a hell of a time clearing the house the next day. “I was like, ‘Wake up! The Trumps are coming. You gotta get up. Get out!’”

“I’m trying not to cry because if I walk out of there crying, they’re going to say I’m crying for a different reason,” she said. When she got on Air Force One, she sobbed for 30 minutes. “The release of eight years of trying to do everything perfectly.”

There is also a fascinating story about the tea she had with Laura Bush between election and inauguration. The White House butlers, mostly older men of color, served them the entire time, all dressed to the nines in tuxedos. In the moment she had a realization of a unique position she was in compared to other first ladies.

She was going to be raising two young black girls in that house. She couldn’t have black men dressed in tuxedos serving them. That’s not the image she wanted them to have of black men in their lives. One of her first acts was to loosen the service staff’s dress code and daily duties.

“I am the former first lady of the United States and also the descendant of slaves,” she said. “It’s important to keep that truth right there. My grandfather’s grandmother was in bondage. People have been taught to believe in the ultimate inferiority of people because of the color of their skin.”

Speaking more broadly about her experience as the first black first lady, she said, “You hope people were more ready for us than maybe they were.”

The burden she had to carry every day took a toll, shouldering the best and the worst the country had to offer. The highs and lows were extreme. She remembers one day that had both. In the morning, she attended the funeral of the men and women who were killed during a Bible study in Charleston. By the time she returned to D.C. that evening, marriage equality for all passed in the Supreme Court.

From inside the White House, which had been lit up like a rainbow, she could hear the LGBT community celebrating outside the lawn on Pennsylvania Ave. She needed to be a part of that feeling of love, especially after that day, one of the only times she pulled rank on security, having just short of a meltdown, and demanded to leave the house and go outside.

The appeal of Becoming is, essentially, what the appeal of the book tour was in the first place. Obama is a magnetic, engaging storyteller, incredibly funny and capable of granting just the right amount of private access into her life to feel like you’re getting to know her—especially with her more casual conversational style outside of the White House.

It’s timely and yet frustrating. It’s a time when people want answers and diatribes and rescue. But Michelle Obama is just raising questions, in dialogue with a nation trying to figure out what the eight years of that administration meant, how to deal with the unease of right now, and where we go from here.

“Barack and I are not interested in being at the forefront forever,” she said. “Not even for that much longer. We got this platform. If you believe in God, God gave us this platform for a reason so let’s not waste it.”

That platform begins streaming on Netflix on May 6.