The OG Cowboy Bebop blasted its premise across its infectious theme: “The work, which becomes a new genre itself, will be called Cowboy Bebop.” And the anime series’ conceit consisted of wrapping popular genre motifs in a 26-minute package. One week, it was a mechanized Space Warrior’s delight; the next, an achingly personal drama, blaxploitation romp, gun-slinging Western, or certified kung-fu flick. The dark, universe-spanning neo-noir followed a trio of bounty hunters—Spike, Jet and Faye—as they hurtle toward their next big score while attempting to outrun their pasts on their spaceship, The Bebop. Its crisp animation, crackling soundtrack, stylized aesthetic and unpredictable world endeared it to fans across the West, making Cowboy Bebop one of the most popular animes of all time.

In the minds of most anime fans, a live-action remake simply cannot recreate the spirit of the medium. Between the by-the-panel approach of the Rurouni Kenshin Netflix films or the very strange, very bad Dragon Ball and Ghost in the Shell remakes, no adaptation can seem to get the formula right. Unfortunately for Cowboy Bebop, fans will continue their search for an adequate remix. André Nemec’s new Netflix series, which stretches each episode to 40-plus minutes, doesn’t really know what to do with more resources and time. Its performances signal that the cast doesn’t appear to grasp the pull of the source material, opting instead for lame slapstick humor and cornball lines (the script is woefully deficient). Cowboy Bebop gets some of the style parts right: the show’s kung-fu scenes, snappy scene-setting, and over-the-top imagery can prove compelling. But where it falters, fatally, is in its misunderstanding of the kind of show Cowboy Bebop is. This isn’t just an issue of translation from one creative medium to another, but rather a complete misreading, transforming a gripping space saga into something utterly childish.

What centered its universe and plot was an overwhelming sense of melancholy. No matter how loudly their ship’s machine guns rang out, how many sly grins Spike would crack at women and nemeses alike, the original was never a show that felt like everything would work out. These characters have been through the wringer, and they acted like it. The series takes place in 2071, 50 years after a catastrophe leaves Earth uninhabitable and the reality of human uprootedness permeates every seam. Ships guided by lonely pilots careen through space, pining for their next meal, a casino to gamble away their last Woolong or bar fight with a stranger, if only to feel some sense of connection. Spike’s exile from his last gang, the mystery behind Jet’s cybernetic arm and police force past, and Faye’s strange post-cryogenic amnesia have left them both physically and psychologically scarred—unable to truly relate with others because they know how finite the world is.

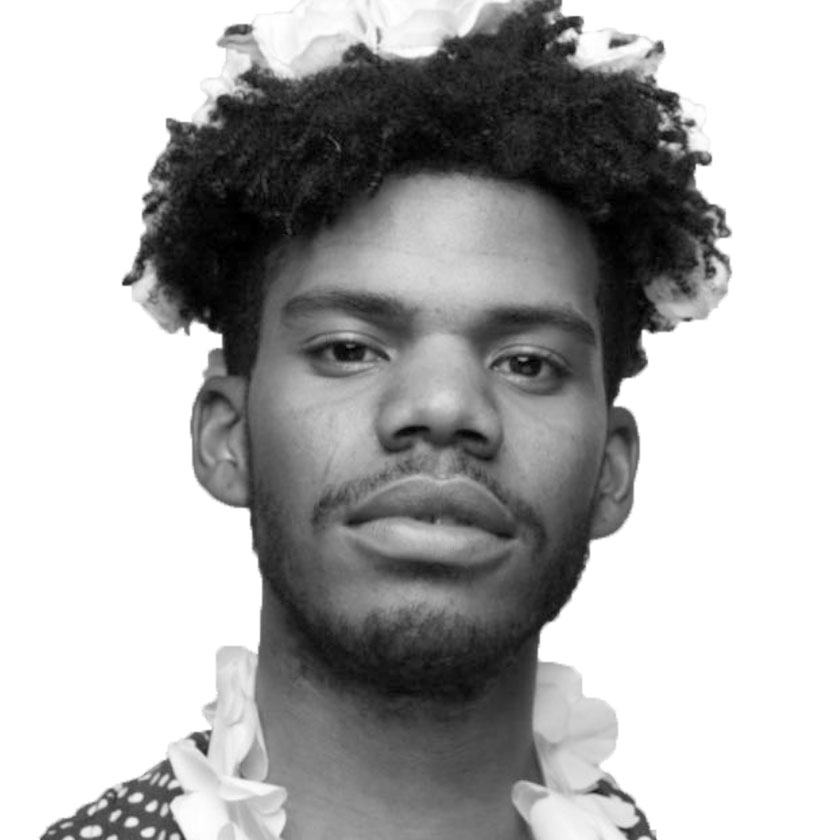

It’s unfortunate, then, that the live-action show doesn’t even broach the deeply interwoven themes and imagery of its source material. Instead, the Netflix series is almost all style and occasional brushes with genuine emotion. John Cho (Spike), Mustafa Shakir (Jet), and Daniella Pineda (Faye) are compelled to really ham up the adolescent nature of the show’s humor. Cho, in particular, is a real missed opportunity—not just because he struggles with Spike’s suave moodiness over the course of the season but also the criticism he initially received (that at 49, he was too old for the part) could’ve worked in the show’s favor in presenting characters who were appropriately damaged. Instead, it feels like Cho is actively trying to play a younger man, and none of it feels natural.

We aren’t really given a sense of what these characters are battling beyond the surface. Spike wants revenge on his former friend; Faye wants to find out who she is; and Jet doesn’t want to become the stereotypical absentee Black dad (okay, he never really says that, but the addition of a whole daughter in the remake is just… why?). The show fails to engage with these existential questions beyond mere exposition, and the emotional scenes are treated as bridges from one eye-catching visual to the next. Gone is the time on The Bebop featured in the original that fleshed out its crew as human beings.

All of this begs the question: What did the production team spend those extra 20 minutes per episode on in the new series?

The answer is Vicious (Alex Hassell), Spike’s arch-nemesis and the Big Bad of the OG run. Back then, Vicious was seen only a few times onscreen—a grand total of 15 minutes or so across the entire run. Here, the show has foregone any mystique by focusing an entire subplot on Spike’s lost love, Julia (Elena Satine), and the results are about as atrocious as the gray wig sitting atop Hassell’s head. I’m not even sure if anyone was fiending for more Vicious; but if they were, they’d probably still be disappointed by the new version. Vicious’ look almost instantly takes away from the seriousness of the character. Hassell is a Brit—a super-questionable choice—looks a mess, and has no distinguishable characteristics outside of, well, viciousness? Plus, that hair is so terrible it must be camp. I’ve seen better wigs on Tyler Perry projects.

As far as plot goes, the greatest harm was brought against Julia, who presents as a pretty fascinating character—one that the show should’ve expanded out more—who is ultimately hamstrung by Vicious’ boring-ass coup d'état. Just kill the gang leader already and let’s get to it.

If taken on its face, the new Cowboy Bebop series does take the premise of its predecessor seriously. In a way, the idea of a Cowboy Bebop live-action jaunt all but solidifies that premise. The show can be a heist, a romcom or a concert series, and it can be played by real-life humans doing real-life human things. Unfortunately, the show’s only connection is aesthetic. It looks like the world and even sometimes—when the energy is high, bullets are flying, or new characters are introduced—can feel like it too. But as a whole, the new Cowboy Bebop is just so ploddingly inefficient and misguided, the idea that it could share the same DNA as its original is farcical. When it comes to stakes, the original is simply in another weight class.