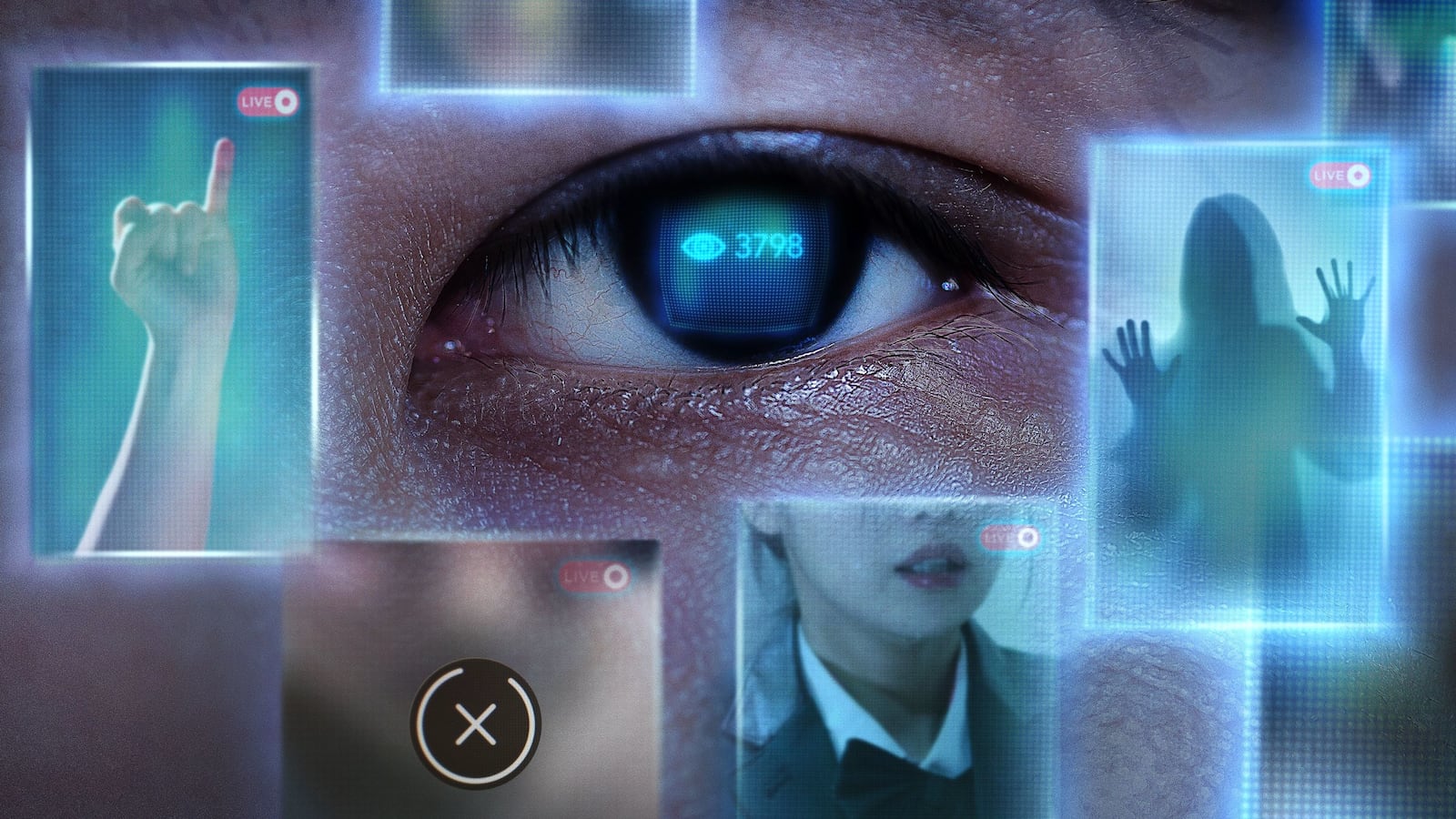

The internet is full of bullies, creeps and monsters, and for another reminder of that situation, Netflix delivers Cyber Hell: Exposing an Internet Horror, the story of the catastrophic danger posed by a simple link received via text or email. Writer/director Choi Jin-seong’s documentary is a cautionary tale about the hazards of trusting everything (or anything) that arrives on your smartphone. Even more than a warning about digital nefariousness, however, it’s a stinging censure of a modern world that, for all its social progress, remains plagued by systemic misogyny.

Premiering on Netflix Wednesday, Choi’s film recounts a case that shocked and horrified South Korea. It begins with The Hankyoreh reporter Kim Wan, who in late 2019 got an email informing him that child pornography was being distributed on an app called Telegram. That alone wasn’t particularly shocking, since Kim remembers thinking that many such stories had already made national headlines. Nonetheless, he followed up on the lead, discovering via his source that a student at a prestigious foreign language high school was distributing this filth in a chat room that had upwards of 9,000 regular members. Together, these teens had shared 19,000 child porn links, and the day after Kim’s report hit newsstands, the subject of his piece was arrested, seemingly bringing the issue to a close.

Except, unfortunately, that Kim soon learned that his own personal information had been leaked onto Telegram—such as his home address and, more menacing still, personal videos of himself and his young children. The perpetrators of this doxxing had also announced that anyone who published his birthdate, the names of his wife and kids, or their phone numbers would earn a prize: the chance to catch a “slave.” What that meant wasn’t immediately apparent to Kim, but The Hankyoreh responded by putting him in charge of a newly created task force alongside reporter Oh Yeon-seo. Shortly thereafter, a source encouraged them to look into the notorious chat rooms run by an individual known as Baksa, and that snooping led them to a user calling himself Joker who, upon meeting them in person, explained (as he does here, on camera, albeit with his identity concealed) the depths of depravity going on in this underground community.

According to Joker, Baksa had become a legendary figure for luring girls and young women into providing personal information (including bank account details) under the guise of offering them modeling jobs. Once they did this and/or clicked on a link he’d text, he immediately blackmailed them into creating and sharing degrading pornography (occasionally involving rape, self-mutilation, and suicide threats) that he would then watermark with his name and distribute throughout the chat rooms, some of which required membership fees to access, and all of which came to be referred to as The Nth Rooms. This venue’s members would subsequently visit and take pictures of these ensnared women’s homes in order to prove that they were in danger should they refuse to comply with Baksa and company’s demands. It was anonymous online coercion carried out on a mass scale, and Kim and Oh were swiftly joined in their sleuthing by TV reporters from JTBC’s Spotlight and SBS’ Y-Story, who were equally committed to tracking down Baksa and this underworld’s other prime bigwig, who went by the moniker Godgod.

Cyber Hell: Exposing an Internet Horror peers into one of the internet’s many ugly corners, where men victimize young women and gleefully enjoy the perverse pornographic byproduct of their crimes. It’s a content mill of exploitation and iniquity, and what made thwarting this business so difficult was the fact that the masterminds behind it were both very good at covering their tracks, and more than willing to intimidate anyone meddling with their activities. Nonetheless, reporters and detectives soldiered on, aided by student journalists (dubbed Team Flame) who had first uncovered the extent of The Nth Rooms’ wickedness, and guided by the belief that what was taking place here was far more heinous than ordinary online harassment and humiliation.

It’s no surprise that Baksa and Godgod were orchestrating their schemes for profit, nor that the financial aspect of their operations was carried out via cryptocurrency exchanges. Following the money turned out to be key to bringing these two cretins to justice, as was good old-fashioned police work involving surveillance and cross-referencing aliases against prior arrests and convictions. As Cyber Hell: Exposing an Internet Horror reveals, tracing the transfer of Baksa and Godgod’s funds was made tougher by their use of the “throwing method”—a practice also common to those behind phone scams and drug deals—in which people would pick up cash on his behalf and drop it in random locations, where it could be grabbed and moved by others in his employ. Add in a variety of additional cagey maneuvers (such as using multiple cellphones and public WiFi networks), and what Kim and his colleagues exposed was a startlingly sophisticated conspiracy.

Choi’s documentary eventually develops into a digital cat-and-mouse game played with IP addresses, routers and extenders, and concludes with the arrest of Baksa (i.e. Cho Ju-bin), Godgod (Moon Hyung-Wook), and 3,757 other people linked to The Nth Room Crimes, 245 of whom have been imprisoned as of December 2020. Alas, while the director fashions his saga as a pulse-pounding thriller (replete with an anxiety-stoking score), he does so through an endless array of dramatic and digital recreations. Aside from talking-head interviews—all of them shot on stage-y sets marked by overly theatrical lighting—as well as a few snippets of CCTV footage, virtually nothing presented by Cyber Hell: Exposing an Internet Horror is formally authentic. As such, there’s a nagging sense throughout that the film is akin to a long-form newspaper article re-enacted for streaming audiences, rather than a work of original non-fiction investigation.

For viewers raised on countless cable-TV true-crime ventures that employ similar reenactment-heavy tactics, Cyber Hell: Exposing an Internet Horror’s lack of genuine documentary material will seem all-too-familiar. Its absence, however, ultimately undercuts the film’s power, just as Choi’s wealth of flashy aesthetic devices—be it whooshing camera pans, digital graphics or overcooked staging and framing—suggests that the portrait he’s presenting is itself somewhat manipulative.