Sen. Elizabeth Warren has built her presidential campaign around the contention that she has a plan for everything—but her plan for winning the Democratic nomination after a disappointing fourth-place finish in New Hampshire is far from clear.

Following her loss on Tuesday evening in what was essentially a home game for the Massachusetts senator, and as she continues to trail the frontrunners in South Carolina polling, plugged-in primary watchers told The Daily Beast that Warren has one last card to play: the caucus state of Nevada.

“If she can even make it here, that is,” a Nevada-based official for a rival campaign said.

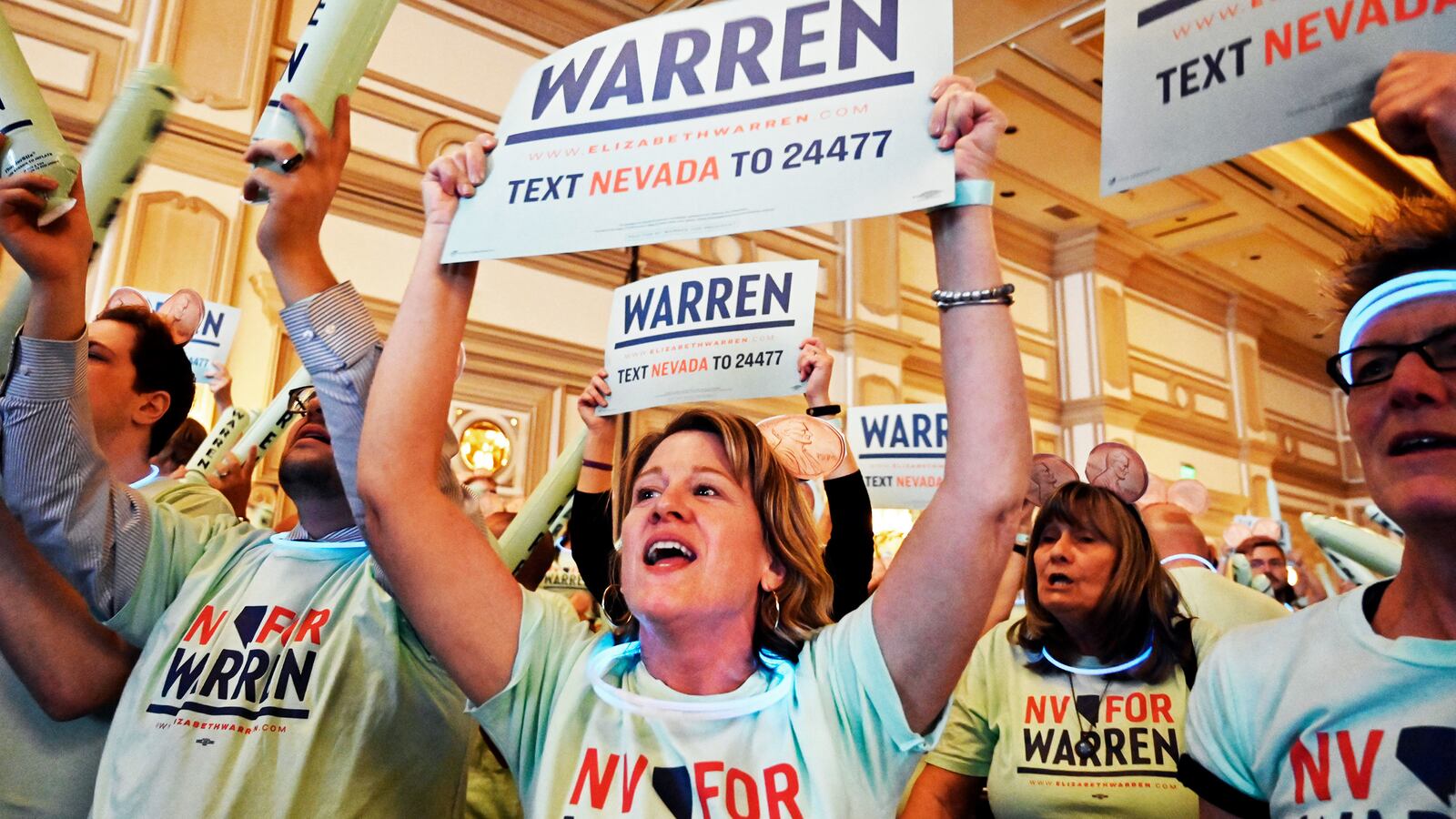

The Warren campaign, which has one of the largest payrolls of any candidate seeking the Democratic nomination, has had an outsized presence in Nevada almost from the outset. The senator has assembled a small army of more than 50 campaign staffers on the ground in Nevada, and has dispatched top-flight surrogates like former rival Julián Castro to the state to underscore her closing “unity candidate” message.

“The Warren team was the first one on the ground here and has a large team with many field offices,” said Donna West, chair of the influential Clark County Democrats, when asked about Warren’s ground game in the state. “They have been working on their grassroots voter contact and engagement, as have most campaigns.”

In a 2,000-word memo released to campaign staff and supporters on Tuesday afternoon, campaign manager Roger Lau highlighted the fact that Warren’s ground team is “closing in on nearly a million contacts” with voters in Nevada.

“Our campaign has been organizing in traditionally red and blue areas of Nevada, South Carolina and states voting in March for months, and in some places nearly a year, and we are confident that we'll continue to show strength by competing everywhere, not just in pockets that reflect one segment of our party or another,” Lau wrote.

In her election night address to supporters on Tuesday, Warren indicated that her team is preparing for a longer, harder primary than she might have hoped for, noting that “we still have 98 percent of the delegates for our nomination up for grabs, and Americans in every part of our country are going to make their voices heard.”

Nevada, the most diverse of the early voting states and a locus for organized labor on the Democratic primary calendar, would normally be a logical target for Warren, whose early investments in on-ground organizing would normally be paying dividends by now. But many voters, West said, remain undecided only days before the state’s early voting period begins on Saturday—and two back-to-back poor showings in Iowa and New Hampshire have some supporters on the ground worried that she won’t be able to compete in the state.

“She keeps saying she’s a fighter, but you have to actually win a fight sometime if you want people to take you seriously here,” an official with one of the state’s influential labor unions told The Daily Beast. The official is personally backing Warren, but their union has not yet made an endorsement ahead of next weekend’s caucuses. “You can’t unify the party from the back row.”

The official noted that Warren aired her first television advertisement in the state only in late January, a 30-second Spanish-language ad titled “Elizabeth Warren Es Una Luchadora” or “Elizabeth Warren Is A Fighter.”

“She’s a fighter who will beat Donald Trump,” the ad’s narrator says in Spanish. “And when the dust settles, she will fight like hell to make this a country that works for everyone.”

In comparison, former Vice President Joe Biden, also on the ropes after dismal finishes in Iowa and New Hampshire, aired his first television advertisement nearly four months ago, and former South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg was up on TV as of December.

Even Warren’s late-to-the-party ads are now being scaled back, however. After the senator emerged from the messy Iowa caucuses with a third-place showing, her campaign pulled six figures’ worth of television ads from the airwaves in Nevada, as well as South Carolina. Warren told The Washington Post that the ads were pulled because she wants to “be very careful” with the campaign’s money, which is running low. According to campaign filings with the Federal Election Commission, Warren’s campaign had a mere $13.7 million at the beginning of 2020.

Warren does still have $2 million in ad buys reserved in Nevada and South Carolina through February, as well as digital ads highlighting praise for the Massachusetts senator from former President Barack Obama (who has not endorsed any candidate yet).

But Nevada is also the early-voting state that Warren has visited the least—one of the many factors that prompted a group of staffers in the state, all women of color, to depart from the campaign last week.

“During the time I was employed with Nevada for Warren, there was definitely something wrong with the culture,” Megan Lewis, a former field organizer, told Politico about the exodus, which amounted to nearly 10 percent of Warren’s Nevada staff. “I filed a complaint with HR, but the follow-up I received left me feeling as though I needed to make myself smaller or change who I was to fit into the office culture.”

Staffers cited the campaign’s late addition of Spanish-language campaign literature and a low number of organizers who could speak Spanish as complicating its outreach to Nevada’s huge Latino population as an additional reason why they left—and did so publicly.

Warren apologized for the reasons that the staffers left after a town hall in New Hampshire last Thursday, saying that she took “personal responsibility” for the departures.

“I believe these women completely and without reservation and I apologize that they have had a bad experience on this campaign,” Warren said at the time. “I take personal responsibility for this and I’m working with my team to address these concerns.”

In the memo released on Tuesday afternoon, Lau outlined the path forward for Warren as a delegate hunt even beyond Nevada and South Carolina.

“The remaining three early states of New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina appear poised to keep the race wide open,” Lau wrote, adding that no candidate “has yet shown the ability to consolidate support” among key Democratic constituencies.

Lau pointed to the delegate threshold of Super Tuesday as the real test for Warren’s candidacy, and revealed that internal projections “show us at or above the 15 percent threshold in… nearly two-thirds of the Super Tuesday map.”

But the time to address concerns about Warren’s pathway to victory—or, at a minimum, survival—in the Silver State and beyond may have already passed, the rival campaign official told The Daily Beast.

“The ‘unity candidate’ message only works if you have something in the ‘W’ column,” they said. “Nobody unifies around third place.”