One day in June 1892, a 28-year-old Black man accused of sexually assaulting a white woman was lynched in front of a crowd of 2,000 spectators. Lynching wasn’t uncommon in post-Reconstruction America—there were over 1,100 lynchings, mostly of African Americans, in the years 1882-1899. But Robert Lewis’ death was particularly noteworthy.

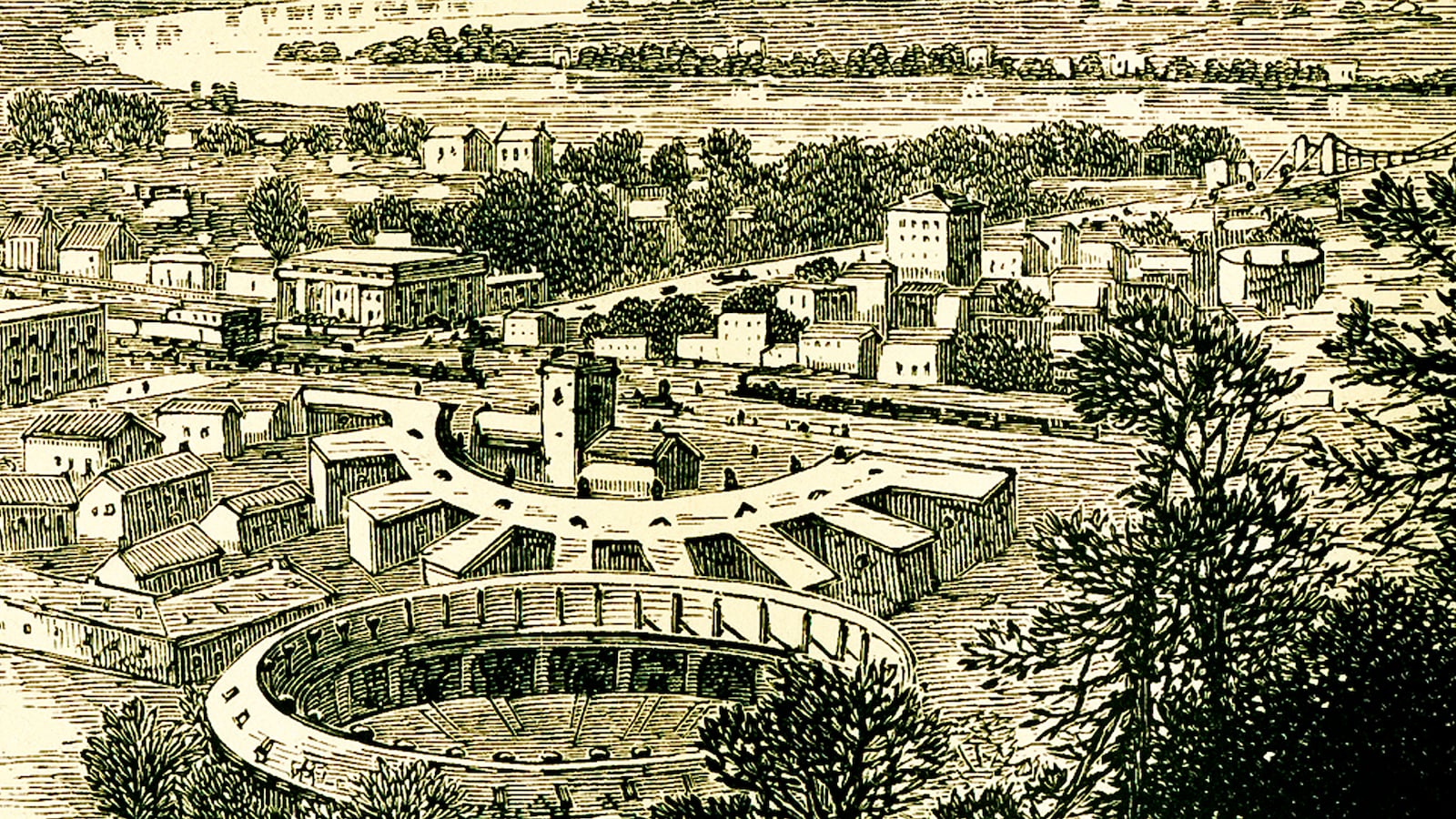

That’s because it was the only one in this era that took place in New York state, in the small industrial town of Port Jervis, which, thanks to its location at the scenic confluence of the Delaware and Neversink rivers, was also a getaway destination for residents of New York City.

More importantly, the event signaled to the world at large that “at a time when the scourge of lynching of Black Americans was ravaging the South, it happened where such incidents were not expected to occur, in a village only 65 miles from NYC,” says Philip Dray, author of the new book A Lynching At Port Jervis: Race and Reckoning in the Gilded Age. “As a West Coast newspaper offered,” adds Dray, “Port Jervis had ‘unsectionalized’ the crime of lynching.”

Port Jervis wasn’t known for racist violence. Only about 2 percent of the town’s 9,000 residents were black, and even though most of them lived a mile away from the main part of the settlement and worked in menial jobs (Lewis was a teamster who drove visitors from the train station to Port Jervis’ main hotel), “there are examples of blacks and whites coming together in places like the local opera house,” says Dray.

But the accusation of sexual assault—and Dray makes it clear that no one knows what really happened between Lewis and his accuser—turned Port Jervis into a mirror image of numerous Southern towns where, he says in his book, “black male lust for a white female became… a vengeful act, a defiance of white male dominance, and a transgression warranting punishment so severe as to blot out the horrible deed itself as well as the perpetrator.”

So after the accusation, and while Lewis was being taken to jail, a mob grabbed him, pummeled him with their fists and slashed him with knives, then hanged him from a large maple tree in the center of town. Finally dead, he was cut down as a large storm descended on the town, and his body was left to lie in the mud for at least half an hour until it was carried away.

Lewis’ murder might have been unique geographically, but in many of its specifics it resembled lynchings taking place throughout the South: the unproven accusation; the lack of due process; the absence of police attempts to stop it; the fact that no one was brought to justice for the crime; and the grotesque gathering of souvenirs of the event (people reached into Lewis’ coffin and took strips of clothing and pieces of hair). There was also what Dray refers to as “‘lynchcraft,’ a kind of aesthetics of lynching, the staging of lynching as a public event,” e.g., “was the family of the person who was the victim of the crime, were they adequately represented” at the event? (In Lewis’ case, his accuser was asked to positively identify her attacker prior to the lynching, but she refused.)

Over 4,000 African Americans were killed by lynch mobs between 1877–1950. Celebrated Black journalist Ida B. Wells called lynching “America’s national crime.” But while Lewis’ death caused a national commotion, it failed to prompt a racial reckoning. The New York Times, for example, while condemning the mob’s actions, also noted that “it is not to be denied that negroes are much more prone to this crime [sexual violence] than whites, and the crime itself becomes more revolting and infuriating to white men, North as well as South when a negro is the perpetrator and a white woman is the victim.”

And, as Dray points out in his book, although the citizens of Port Jervis were aware of committing a great wrong, the town’s “focus stayed for the most part on its own wounded reputation and was noticeably lacking in regret and compassion for the lynching’s actual victims: Robert Lewis, his family, his friends and his neighbors.”

Yet the event did have some interesting after effects. Stephen Crane, author of The Red Badge of Courage, lived in Port Jervis for several years and was inspired by the lynching to write an 1898 novella, The Monster, about a Black man horribly disfigured in a fire who becomes a social pariah. Contemporary critics view the work as a scathing study of prejudice and fear in a small town, and, writes Dray, Crane “had chosen to confront a question largely evaded by late nineteenth century America: How should a conscientious white person respond to the most egregious forms of racial prejudice?”

More importantly, Ida B. Wells, who believed that the unsupported accusation of any white person for any reason was sufficient cause for a lynching, used Lewis’ murder as the beginning of a campaign to end the practice in this country. Her 1892 pamphlet “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law In All Its Phases” was one of the first to fully document the institution and its origins in white fears of Black economic progress. This led in 1900 to the introduction of the first federal anti-lynching legislation in the House of Representatives, a ban that did not become law until April of this year, a 120-year uphill struggle that, says Dray, was due to the fact that “any federal meddling in the South after 1870 was seen as over-reach and unwelcome. And the Southern bloc [in Congress] was just too strong. Always with these kinds of things, intolerance and a lack of willpower” are impediments to getting these kinds of laws enacted.

At least Port Jervis, which for many years forgot all about the incident, is now willing to recognize it. This June 2, on the 130th anniversary of the lynching, a plaque memorializing the event will be dedicated at the site of the atrocity. The plaque, which has been paid for by the State of New York, reads “Racial Lynching. On June 2, 1892, Robert Lewis was beaten, stabbed and lynched by a racially motivated mob. A great injustice is recognized.” The dedication also corresponds with what has become known as the annual Robert Lewis Remembrance Walk.

And there’s this. Although 1952 was the first year without a lynching, and 1967 marked the first conviction of a lynch mob in the modern era—seven Klan member were convicted of the murder of three civil rights workers—Dray says in his book that “the spectacle of bystander-made cell phone videos and police body-cam footage serve in not dissimilar ways as witnesses to, and as amplification of, the summary execution of Black people.”

Plus, the events of Jan. 6, says the author of A Lynching at Port Jervis, prove that mob violence provoked by white fear of change is still with us. “Looking at the videos of January 6th, you can imagine what happened on the streets of Port Jervis,” says Dray. “January 6th was a white reaction to unacceptable change, that the country was slipping out of their hands. I think there was some of that in the 19th century.”