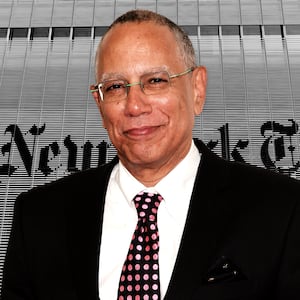

New York Times executive editor Dean Baquet admitted Monday that the paper can and should do a better job covering race in the era of President Donald Trump.

During a hastily arranged meeting, lasting well over an hour, top Times leadership addressed the paper’s staff about public criticism the outlet has faced in recent weeks centering around its coverage of Trump, race, and politics.

Among the many topics discussed during the lengthy meeting were two recent embarrassments for the paper: A credulous headline that characterized Trump’s post-mass shooting televised speech as a sincere call for national unity; and to a lesser degree, the Twitter behavior of Times deputy Washington editor Jonathan Weisman.

Also on the agenda was discussion of when to use labels like “racist” in Times stories, and the paper’s decision several years ago to dispense with the public editor position—that is, the independent in-house critic whose role was to assess Times journalism on a daily basis.

Throughout the meeting, during which Times publisher A.G. Sulzberger also spoke—not the norm—Baquet reiterated much of what he has publicly said about the challenges the paper faces in an era of hyper-polarization and media distrust.

But he also acknowledged that the paper has work to do, conceding that the Times had “a couple of significant missteps.”

Much of the meeting focused on outrage over a headline last week following multiple mass shootings, including one in El Paso that authorities have said was seemingly motivated by racial hatred. The headline, which proclaimed “Trump Urges Unity Against Racism,” faced criticism both outside and within the paper among those who said the publication was papering over the president’s history of racist comments and how Trump seemed to focus on other issues, including violent video games, more than racism and xenophobia.

“He’s sick. He feels terrible,” Baquet said of the person who wrote the offending headline.

The top editor reiterated that the headline was a mistake—“It was a fucking mess,” he told the staff—but joined other newsroom leaders in cautioning staff not to overreact to Twitter comments about the paper’s editorial decisions.

Baquet said the paper shouldn’t allow itself to be edited by Twitter outrage. When it was his turn to speak, Sulzberger cited a statistic claiming that only a small number of people tweeting about Times stories actually clicked on them, suggesting many readers judge the stories before actually reading them.

Last week’s headline reignited an ongoing media discussion—both inside and outside the paper—about how to properly cover Trump’s racist statements.

During Monday’s meeting, Baquet, the first African-American executive editor of the paper, emphasized that rather than simply labeling the president or other leaders “racist” or using euphemisms like “racially charged,” the paper should demonstrate instances of racism through concrete examples.

But Baquet said he was open to further discussing how the Times could better cover issues around race, encouraging staff to visit him in his office, and pointing out that the paper was focused on having more reporters from different backgrounds to cover politics and race.

The executive editor also said the Times’ standards editor is working on producing a written standard for when the paper should use the word “racist,” and cited clear examples of reporting where it could be used—such as when Virginia’s Democratic Gov. Ralph Northam’s college yearbook page included a photo of someone in blackface costume.

The meeting also comprised a laundry list of issues discussed about the Times: Baquet addressed the lack of a public editor, as well as whether the headline missteps were a result of the paper cutting copy editors.

But while the masthead fielded questions about a number of recent controversial decisions, some staff felt the meeting largely glossed over criticism of Weisman, a top editor in the paper’s Washington bureau who last week drew widespread criticism for his online behavior.

In a first bout with controversy, Weisman suggested that Detroit-based Rep. Rashida Tlaib (D-MI) and Minneapolis-based Rep. Ilhan Omar (D-MN) are not really from the Midwest, and that Rep. John Lewis (D-GA), a black civil-rights icon from Atlanta, is not actually from the Deep South. Several days later, Weisman drew further outrage when he separately emailed famed writer Roxane Gay, her assistant, and her publicist demanding an “enormous apology” for her criticism of his tweets about a congressional candidate of color.

The latter incident prompted a rare public chiding from the paper itself. “Jonathan has repeatedly displayed poor judgment on social media and in responding to criticism. We’re closely examining what to do about it,” the Times said in a statement last week.

The top editor said he’s personally pained when he sees his journalists conducting themselves inappropriately on Twitter, not least because “it destabilizes the newsroom,” according to a New York Times source. Baquet argued that reporters’ tweets should not be anything that couldn’t appear in the paper.

“The thing that surprised me was that the Jonathan Weisman issue didn’t come up more, because it has had the newsroom in absolute meltdown for the past week,” one Times staffer told The Daily Beast. “I think the big question that people have right now is, ‘Is this guy going to get suspended?’ What’s going to happen to him? It’s a really big deal.”

The staffer added: “He’d already been told to shut the fuck up on Twitter” after an earlier flap. “From a reporter’s perspective, when editors are spending time on Twitter saying things that are wrong or embarrassing, it just feels so undermining to the work that you’re doing, covering shootings and all kinds of stuff. And then people are like ‘fuck the New York Times. I’m going to cancel my subscription because this editor in Washington said something idiotic.’”

Baquet, who is widely liked and respected in the Times newsroom, was “his usual unflappable self,” said this person. The executive editor fielded tough, sometimes adversarial questions without being defensive, the staffer said, and repeatedly invited staff to his office for private conversations.

“I hope it went well,” Baquet told The Daily Beast in a text message. “I just want a newsroom where people feel they can talk about coverage and complain to me.”