‘Downstairs’

Broadway producers, some strange timing and some good news all at once. Sunday night, off-Broadway, two excellent shows opened that you should see immediately.

There is a monster in Tyne Daly’s basement. But is it her husband or brother, or both?

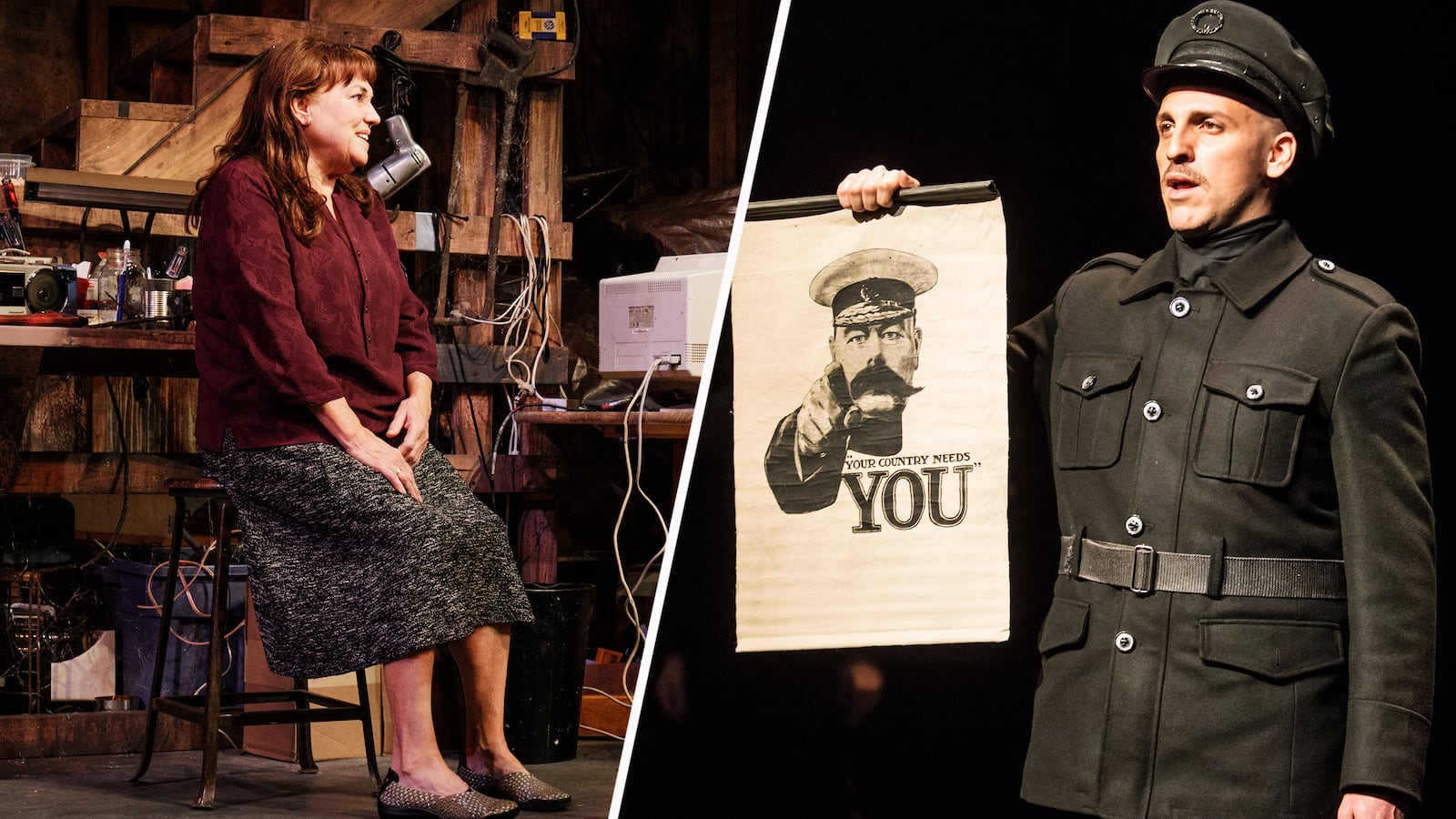

In Theresa Rebeck’s lean, tense thriller and psychological drama Downstairs, the former Cagney and Lacey star plays Irene, a harried and nervous woman with a brother, Teddy (Madam Secretary star Tim Daly, Tyne’s brother) who has suddenly taken up residence in the basement of her home.

The basement is the setting of this Primary Stages play at the Cherry Lane Theatre. It is so beautifully and so evocatively designed by Narelle Sissons you can smell the damp and chipboard is the fourth character in this play, which is directed with a fine sense of claustrophobic menace by Adrienne Campbell-Holt. (Do check out Daly's modesty-first bio in the program: no mention of her award-laden, famous TV-show career, but rather that she made her professional debut at the theatre in 1966, and “She is delighted to have been invited to play here again.”)

The basement is cluttered, homely, and also somewhere you want to get out of immediately. It is packed with tools, and is the territory of Irene’s husband Gerry (John Procaccino), unseen in the early stages of this play even if the foreboding thuds we hear we think must be his feet above.

Until we meet him, we see the nervous dance between brother and sister as played by the real life brother and sister. Tim Daly’s Teddy seems, in some way, vulnerable. He is nervous, skittish, untethered and odd: he says he has a grand new life plan, a job in the offing, and just needs some sanctuary for a while.

There is a fractured vulnerability in Teddy, a sense he is not strong enough for the outside world. But there is also his intelligence, his accurate reads on people and situations, and there is something in his manner—his flicks of cruelty towards his sister—that make us worried.

Tyne Daly sensitively and intelligently plays Irene as walking on multiple eggshells at every turn. She is the big sister, and of course she will take care of her brother. But she isn’t sure if he is telling the truth, she isn’t sure of him at all. He knows her better than anyone, their bond is strong, but he is also a danger to her married life with Gerry, as the two men cannot stand one another.

If this sounds an emotional drama, it is also a practical one. The house, in Teddy’s estimation, belongs to him and Irene. It was bought with their family’s money. Yet she calls it Gerry’s. So does Gerry.

Teddy is incredulous that Irene would have a problem with him using the basement. “You’re not using it! It’s empty space. It’s empty. It’s undefined. It has no purpose. If I want to claim it, even for a few days, as a haven, a place of rest, a moment of calm, a cave, a life raft—I have a moral right. You know, to do that.”

But for Irene, while “there is no question that we share a history and a bloodline,” it is “also clear that that means something but at the same time more and more the question What reasserts itself. What does it mean. What is the obligation. What is he doing here? What is he trying to get away with this time? What is he up to? What the HELL is he up to?”

Both Irene and Teddy are vulnerable, Irene seeming a little more buttressed in the world by dint of her marriage. Teddy tells a story, which sounds paranoid and delusional, about being stabbed by a poisoned pen at work.

Teddy is sure an ancient computer in the basement works. He tinkers with it until it does and he is shocked by what he finds. He talks to himself. His sister brings him ziti and cheese and sausage. She bakes him a cake. They remember their mentally ill mother, who Teddy recalls screaming at dishes in the sink. Irene doesn’t recall this, and something in Tyne Daly’s squirrelly manner suggests she doesn’t want to. Instead, she recalls cuddling her scared little brother.

Rebeck increases the tension because we can see both brother and sister are so complexly intertwined; and we also know the living situation cannot continue as it does. When Irene confesses that her husband is “just a horrible man,” it confirms to Teddy that Gerry has the “demon” inside he always thought he had. Irene breezily lays out the scale of her husband’s control and gaslighting. She both knows it, and cannot bear to acknowledge it.

Teddy tells his sister, “There are good people in the world, and there are bad people. And the bad people aren’t necessarily smarter than the good people. I don’t personally think they are smarter, that wouldn’t make any sense. But they will do things that good people won’t do. And they know that we won’t do them. And so ultimately all the good people have to hide in the basement.”

The sight of Gerry’s feet on the stairs are enough to terrify us. They certainly, reasonably, terrify Teddy. Irene is out shopping. The real-life Daly brother and sister team play the fictional brother and sister as damaged and tender around one another, while Procaccino is the terrifying bear that could wreck them singularly or together.

Gerry owns this space, he makes clear. Physically strong and thick-set, your eyes scan the tools around the basement which suddenly look like weapons. Procaccino plays the domestic terrorist with a terrifying, snake-eyed focus, insisting in his most chilling speech that “people don’t care about anybody.” Matters eventually lead to a dramatic final confrontation.

This confrontation isn’t quite what you expect it to be, but it uncovers the true, grimy underbelly of Irene and Gerry’s marriage, and your eyes flick to those dangerous tools again. Watch at the meaningful, fragile roots of Irene's recovery: her dowdy clothes replaced by a vibrant green coat, the color of returning life.

In some ways how Rebeck writes this confrontation and a meaningful epilogue to the play both show Rebeck's unconventional approach to the play's juiciest scenes. Michael Giannitti's lighting, which has softly lit this space suddenly becomes harsher. The spell, the uneasy peace, is broken. Suddenly everything is seen.

We are not, finally, shown things we expect to be shown, nor necessarily hear things we expect to hear. But Downstairs is a thriller and convincing marital and family drama that says a lot in its silences, and with excellent performances from its three actors that make this particular basement somewhere you never want to be again.

Downstairs is at the Cherry Lane Theatre, NYC, until December 22.

‘All Is Calm: The Christmas Truce of 1914’

What a lovely space the Sheen Center For Thought & Culture’s Loreto Theater on Bleecker Street is: stately, warm, and welcoming. Appositely, the exquisitely performed All Is Calm: The Christmas Truce of 1914 is reaching out intimately and powerfully to audiences there.

Not all the seats were occupied at the performance this critic attended, and every seat should be. And, Broadway producers note: this 75-minute show would flourish on a bigger stage too.

The story is well-known: in the first year of World War One, hostilities along extensive sections of the Western Front late on Christmas Eve and into Christmas Day, 1914, ceased. English and German soldiers emerged from their respective trenches to cross ‘No man’s land’ and meet one another. For these few precious hours, the sound of gunfire ceased. Songs were sung, gifts exchanged, and—although this has been disputed—games of football played.

All Is Calm, written and directed by Peter Rothstein, with vocal arrangements by Erick Lichte and Timothy C. Takach, and music direction by Lichte, takes an intelligently clear approach to this complex material. All Is Calm had its world premiere on Minnesota Public Radio in 2007, since when the award-winning show has been broadcast on five continents. As a stage show, it has toured the United States for ten seasons.

On a simple and stark black stage, with occasional jets of theatrical smoke to evoke the battlefield, the play intersperses popular songs sung by soldiers of the time with actors reading the memories and letters home of real soldiers and famous poets of the era, like Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon.

This fantastic company of actors—Sasha Andreev, David Darrow, Benjamin Dutcher, Ben Johnson, Mike McGowan, Tom McNichols, Riley McNutt, Rodolfo Nieto, James Ramlet, and Evan Tyler Wilson—sing beautifully in harmony and a capella.

Versatile of accent, they initially play British soldiers of all classes and kinds heading off to war, with jokes and joshing and brightly optimistic songs like ‘Pack Up Your Troubles In Your Old Kit-Bag, and Smile, Smile, Smile.’ But reaching the front means coming into contact with the grinding, awful reality of trench warfare, including getting acquainted with large rats that are far too tame and unafraid of humans.

Death is soon all around the men, as is cold, sadness, and isolation. And then there is that night itself, which is beautifully lit on stage by Marcus Dilliard, with softly falling snow and a waxy moon.

In 1914 that night began with the sight of candles and lights hung above the German trenches. The English and German versions of 'Silent Night' and other songs were sung into the frigid air. And then the soldiers rose to meet one another, trusting, correctly, that neither side would abuse this tender bond of peace, however temporary it would prove to be.

Piercing memories of fraternal association are recalled as the cast play soldiers from both sides. We see the moments where each side allowed the other to bury behind their lines those whose bodies lay in No Man’s Land and then those games of football. Rum is opened, cigarettes exchanged, letters from home read. The men wonder how this can happen, how they can be so close, and be expected to kill each another.

Of course, the play has a tragic ending we know too well; the Christmas truce was short-lived. The men were ordered back to war. We hear of the moment where a German soldier stood on the top of his trench, probably still thinking the truce was still extant. He was shot. The fighting began again. Over 16 million people died during World War One.

One character wonders if the truce, had it held, could have led the men away from the trenches, and ended the war. (Probably not. The various countries’ leaders would not have countenanced such mass desertion.) The superb All Is Calm leaves us mulling the terrible futility and cost of war, while crystallizing a moment of beautiful humanity.

All Is Calm: The Christmas Truce of 1914 is at the Sheen Center for Thought & Culture, New York City, until Dec. 30.