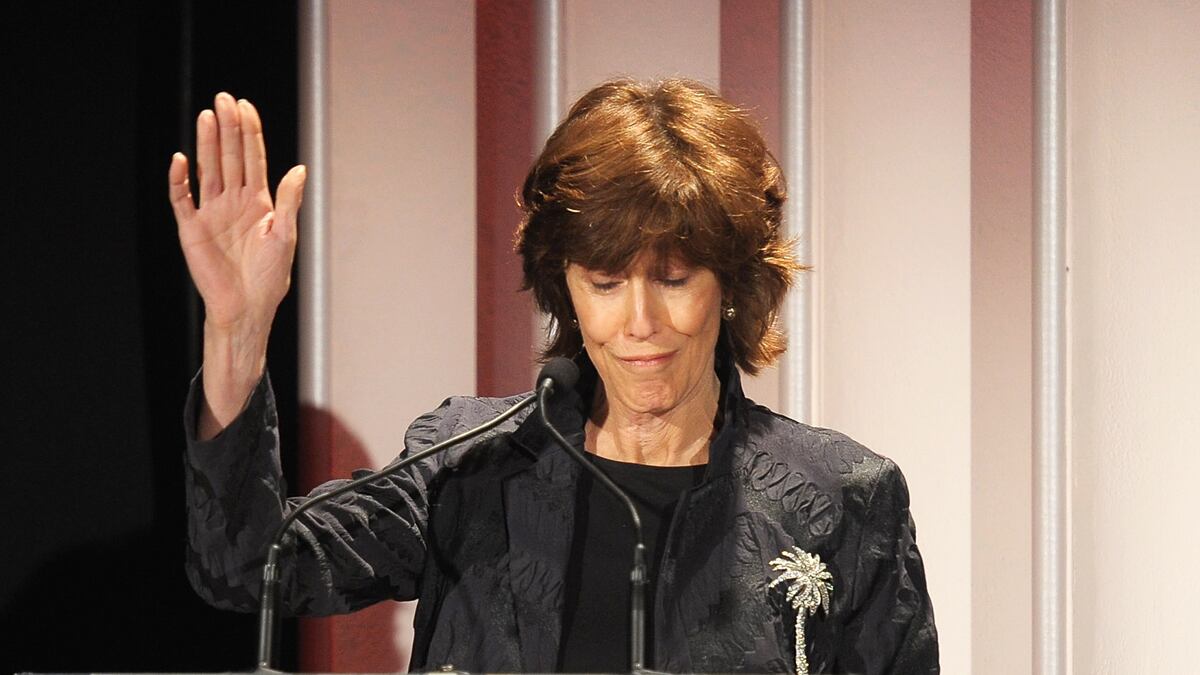

Nora Ephron, the film director, writer, and humorist who died Tuesday, June 26, at 71 of pneumonia caused by acute myeloid leukemia, spent the last weeks of her life in New York Presbyterian hospital on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, a few blocks from her apartment. Until hours before her death, no one except her family and closest friends knew she was even ill.

“That was the way she wanted it,” said Richard Cohen, The Washington Post columnist who had known her for more than 35 years and who was among those at her bedside. “She was a very open person, someone who wasn’t afraid to live her life in public, but this she wanted to have control of.”

Ephron, who gained literary fame as an essayist and Esquire writer during the 1970s and eventually became one of the few women to write and direct a slew of major commercial hits, including You’ve Got Mail and Sleepless in Seattle, was diagnosed with myelodysplastic Syndrome, the precursor to acute myeloid leukemia about five years ago. The disease progresses to the fatal form of leukemia in about 30 percent of cases.

“What kind of place is this?” asked the director Mike Nichols, when he was informed that Ephron had died. Nichols directed Heartburn, the 1987 film that Ephron wrote, based on her own thinly novelized account of her calamitous marriage to Carl Bernstein, of Watergate fame. “I feel like someone reached in and grabbed my compass from around my neck and threw it from a moving train. How will I navigate?”

Ephron, according to Nan Talese, the book editor who is married to Gay Talese, one of Ephron’s close friends, said Ephron had planned carefully for her death, leaving an “exit memo,” with a list of people she hoped would speak her funeral. “She got the idea from [Time magazine editor in chief] Henry Grunwald. He had left a list like that and Nora was on it. It made an impression on her.” Ephron, said Talese, was “brilliant, funny, and dangerous to be with. She lived life acutely observed at every moment.”

Married three times (her first husband was the humorist Dan Greenburg), she is survived by her husband, Nicholas Pileggi, whose book, Wiseguy, was made into the Martin Scorsese film Goodfellas, and two sons, Jacob, a correspondent for Newsweek and The Daily Beast, and Max Bernstein, a musician.

The first of four daughters of the screenwriting team of Henry and Phoebe Ephron—all became writers—Ephron was born on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, but moved with her family to Beverly Hills when she was 4. She attended Wellesley College, and became a summer intern in the Kennedy White House. Her first postcollege job was at Newsweek as a “mail girl” in 1962. That year, during an infamous newspaper strike, she was among the writers who worked on a parody of the New York Post, which caught the eye of Post owner Dorothy Schiff, who hired her as a reporter. While there, she wrote wry profiles of Ayn Rand and “Cosmo Girl” Helen Gurley Brown. Her knowing style on the page was a revelation. Until then, women feature writers tended to be cheery and breathless.

Ephron later moved to Esquire, then at the center of New York literary culture in the 1970s. Her 1972 essay about being flat-chested, “A Few Words About Breasts,” broke new ground and helped create the genre of personal writing that is now ubiquitous. With Gay Talese and Tom Wolfe, she became one of the chief practitioners of the “New Journalism.” Her style was tart, clear, and full of juicy punchlines. Her high gloss prose kept the personal revelations from seeming overly sincere or maudlin.

Such panache would also characterize her films. Her first screenwriting gig was doing a draft of the movie version of All the President’s Men, starring Dustin Hoffman as her then-husband. The version she and Bernstein wrote wasn’t used, but in 1983 she wrote Silkwood. Mike Nichols, who directed that film, said today that Ephron “was so funny and interesting that we didn’t notice she was necessary.”

Her biggest hit came in 1989 when her script When Harry Met Sally was made into a Rob Reiner movie with Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan. Ephron’s first effort as a director was the 1992 This Is Your Life, based on a Meg Wolitzer novel. She co-wrote the script with her sister Delia, but the film flopped. A year later, however, Sleepless in Seattle, with Tom Hanks, was a huge success, and You’ve Got Mail, in 1998, was also box-office gold. In all, she directed eight films and earned three Oscar nominations. Her last movie was the 2008 Julie & Julia, with Meryl Streep playing Julia Child.

But Ephron always considered herself a writer first. Her early essay collections, Wallflower at the Orgy, Scribble Scribble, and Crazy Salad, were filled with brilliant, sharp writing that influenced a generation of journalists who pass her work around like contraband. Not only did she continue writing essays—her 2006 collection I Feel Bad About My Neck, topped the bestseller lists—but with her sister Delia, she adapted the off-Broadway version of Love, Loss, and What I Wore, a book by Ilene Beckerman.

Talese said Ephron had finished a new play recently that will be produced in the coming season. “She never stopped until she was stopped,” she said.