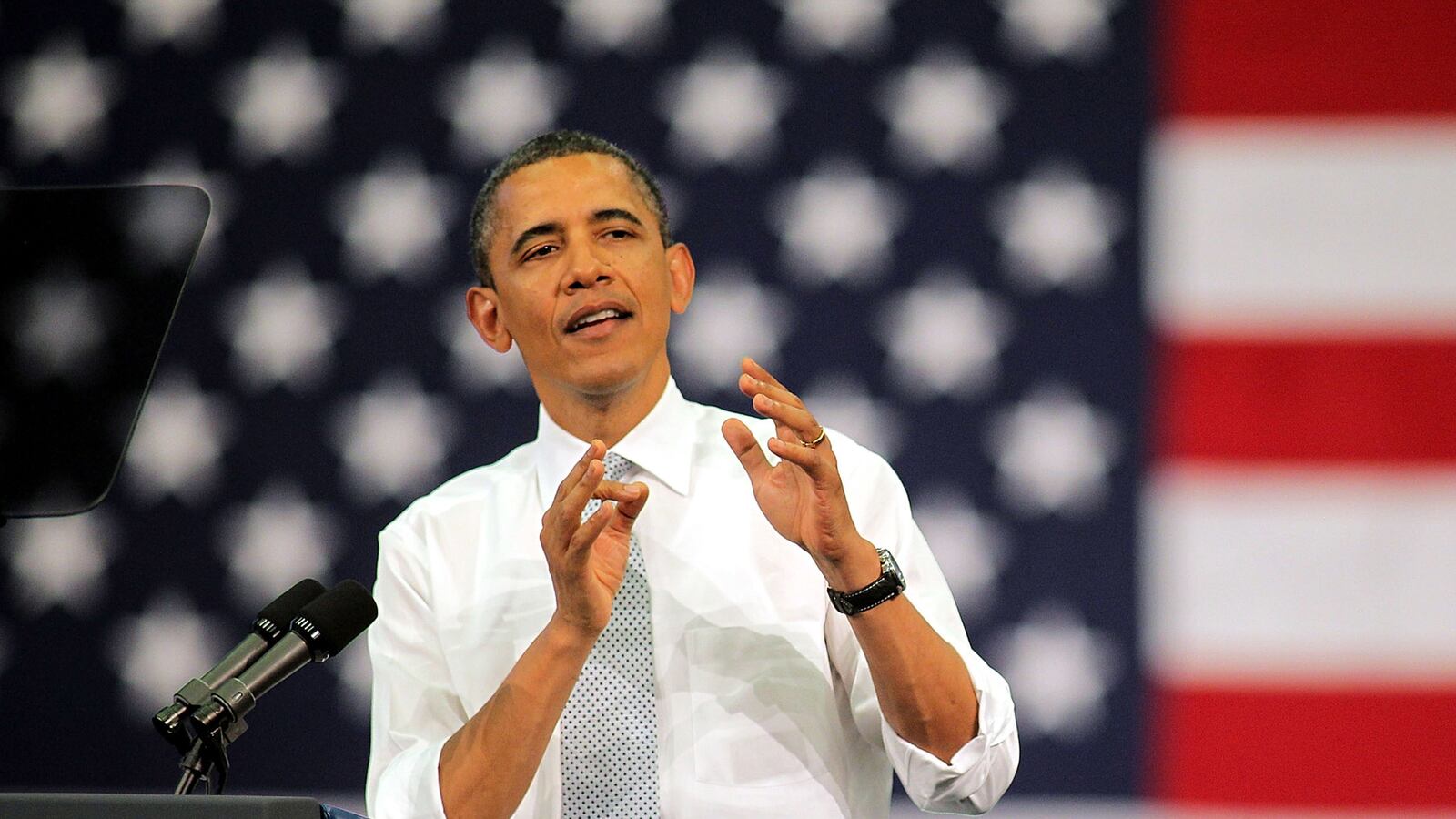

That’s the one question about the present push for the “Buffett Rule” that President Obama can’t answer—at least not without exposing his own proposal as the shabbiest, sleaziest sort of partisan posing.

If the president cared sincerely about “tax fairness,” or the importance of millionaires paying a “proper” percentage of their income to the government, then why did he do nothing to address these issues during his first three years in the White House? This challenge applies with special force to the two years 2009 and 2010, when Barack Obama enjoyed overwhelming Democratic majorities in both House and Senate. Had he suggested the Buffett Rule in, say, April 2010, the Hope-and-Change intoxicated Congress of Nancy Pelosi and Harry Reid would have passed it without delay, claiming at least partial progress in fulfilling Obama’s often-repeated campaign promise to raise taxes on the rich.

But the president never fought for anything like the Buffett Rule when he easily could have prevailed in the battle, so what changed in the intervening months to make a tax adjustment they never even debated two years ago seem suddenly urgent and important?

Of course, the Republicans won sweeping victories in November 2010 and that dramatically altered the political climate in the Capitol. But since Big Bad Boehner rode to power, his GOP Wild Bunch failed to make any major changes in the tax code, and enacted no new breaks or giveaways for millionaires. The same favorable treatment of investment income, the same exemptions and deductions and tax dodges that so offend the president in 2012, existed in all their glory when he first came to office in January 2009. The president can blame the new Republican majority for blocking many of his more ambitious spending initiatives, but he can hardly blame them for the sorry state of a disastrously dysfunctional tax code that’s remained largely unaltered in the Obama era.

If anything, the tax system looks less favorably on the rich than it did when this president took power; he’s not only introduced new levies on the prosperous as part of Obamacare, but proudly passed a two-year payroll tax reduction that saves 2 percent on all income below $108,000. The Democrats can hardly explain their newfound enthusiasm for a minimum tax rate on high earners by claiming that the administration they ardently admired presided over a shift in a less progressive direction.

Nor can they claim that this minor but mercilessly hyped alteration makes a serious dent in the deficit. The administration’s own figures show that even in a best-case scenario the Buffett Rule would generate less than $5 billion a year—amounting to less than 0.5 percent of the current $1.2 trillion deficit and less than 0.1 percent of the $45.4 trillion the federal government will spend.

If the deficit crisis counts as such a dire emergency that even a reduction of one-half of 1 percent merits this ferocious tax fight, then why did the president ignore a similarly desperate situation in 2009, 2010, and 2011? Of course, he would say that he addressed the problem previously by calling for an end to Bush-era “tax cuts for the rich” but those changes—which Obama ultimately abandoned—would have delivered an estimated $70 billion in added revenue per year. That’s still barely 5 percent of the deficit (in the most optimistic projections) but it’s 14 times more than the anticipated haul from the Buffett Rule.

Of course, in December 2010, President Obama gave up on his deeply desired tax hike for families bringing home more than $250,000 per year in part because of fears that any sharp increase in taxation could imperil a still-fragile recovery. In the only possible nonpolitical answer to the question of why he waited till now for the Buffett Rule initiative, the president might say that today’s stronger economy could handle any shock and shoulder any new burden far more readily. But this logic flies in the face of the common conviction that the recovery is still struggling to gain traction, as evidenced by major market reverses and job-creation setbacks in early April. Most Americans still perceive the economic growth of the nation as uncertain at best, hardly robust and inexorable. Why, then, risk losing any momentum at all for a purely political gesture that will do nothing significant to fix our fiscal mess?

And the risks count as far more serious than any possible reward, since the proposed change would double (from 15 percent to 30 percent) the rate of investment tax for many of the nation’s most significant investors. If you counted yourself among the lucky few who earned more than a million a year from your portfolio, and if you knew that starting on Jan. 1, 2013, you would pay twice as much in taxes on capital-gains income than you would today, wouldn’t you feel impelled to sell off significant assets in the low-rate months remaining to you? The impact on the stock market of the resultant tidal wave of sell orders would bring a sharp, painful reverse if not an outright crash, damaging middle-class investors and pensioners at least as much as Wall Street biggies.

For this reason and many others, the president knows that he’ll make no progress on winning passage for the Buffett Rule, so he can demagogue to his heart’s desire with no risk of real-world consequences. On this issue, Dems draw a freebie—getting to unleash impassioned rants on “fairness” while the reviled GOP House stolidly and reliably prevents their populist nostrums from doing actual damage to the economy. Barack Obama waited till the heat of a reelection campaign to conjure up the specter of a new tax on millionaires in part so he could make Mitt Romney the preferred poster boy for evil plutocrats who pay lower tax rates than their secretaries. Never mind that Romney’s massive gifts to charity would probably spare him from any new personal liability even in the unlikely event that the Buffett Rule became law—since Obama insists that even the wealthiest taxpayers could continue to deduct their charitable donations. When combining his contributions to charity with his federal, state, and local taxes, Mitt shelled out more than 40 percent of his income over the last two years to help other people—that is if you think tax payments to government actually help other people.

Employing one strategy or another, the top-earner targets of the Buffett Rule would deploy their armies of accountants and attorneys to reduce its personal impact, but the damage to the stock market and the economy in general could be significant. This highly touted “reform” represents the very worst sort of policy proposal, with real risks to the private sector and no real benefits for the government. Politically, on the other hand, it provides the president with a convenient cudgel to batter his opponent while cynics in politics and media wink and shrug at a silly agenda item that will disappear in 2013, even if Obama is reelected. Few insiders, in fact, take the current debate seriously enough to confront the president with the question about timing he can’t possibly answer without embarrassment.