Game of Thrones, Conan the Barbarian, and his outings as DC superhero Aquaman proved that Jason Momoa is an intensely intimidating presence.

Yet his dynamic comedic work in A Minecraft Movie also underlined that he’s capable of playing more than just menacing brutes—which makes his turn in Apple TV+’s historical drama Chief of War so underwhelming.

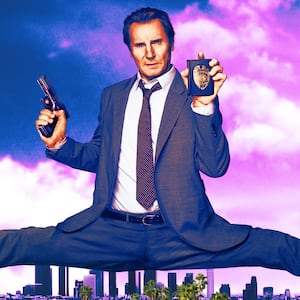

Often decked out in nothing more than a feathered cape and a rear end-baring loincloth, Momoa radiates brutal ferocity as Hawai’ian warrior Ka’iana. However, over the course of its nine hours, the show—created by the actor and Thomas Paʻa Sibbett and premiering Aug. 1—has him do little more than scowl and shoot daggers from his eyes.

With a perpetually angry look affixed to his face, the headliner growls and rages through this tale of tribal warfare at the turn of the 19th century, exuding captivating strength and fury and, unfortunately, not much else. If they handed out Emmys for glowering, he’d be a shoo-in. Yet in terms of delivering a multifaceted performance, he’s sabotaged by material of his own design.

Based on real events but cast in mythic terms (complete with an absurd amount of momentous slow-motion), Chief of War revolves around Ka’iana, whose father was the chief of war to Maui’s King Kahekili (Temuera Morrison).

Because he didn’t believe in the warmongering ruler, Ka’iana abandoned Kahekili to live as an outcast on Kaua’i with his loyal family, which includes wife Kupuohi (Te Ao o Hinepehinga), brothers Namake’ (Te Kohe Tuhaka) and Nahi’ (Siua Ikaleʻo), and Kupuohi’s sister Heke (Mainei Kinimaka).

That self-imposed exile doesn’t last long, as Kahekili summons Ka’iana back to Maui to convince him to lead his army into battle against the boy king of O’ahu, who’s been counseled by an evil High Priest into waging war against their people. Moreover, Kahekili says that his Seer has pronounced that an ancient prophecy—claiming that a great king will unite the island kingdoms—is now upon them, and that it’s Ka’iana’s destiny to facilitate Kahekili’s victory.

Despite his reservations, Ka’iana agrees to this assignment, only to learn that he’s been duped by Kahekili, who’s just what Ka’iana imagined him to be: a deceiver with conquest on his mind. Chief of War eventually reveals Kahekili to be a bloodthirsty tyrant who thinks that the sole way to bring the kingdoms together is to destroy all royal bloodlines save for his own.

It’s a plan that rankles even his son, Prince Kūpule (Brandon Finn), whose loyalty is put to the test as his dad devolves into a cartoon-villain mad king, complete with drug use, murder, and orgies. Though he was told by the Seer that he was destined to stand with the Prophesied One, Ka’iana quickly comes to see that Kahekili isn’t that guy, and he’s profoundly heartbroken by the massacre he’s been tricked into perpetrating against innocents.

Sensing Ka’iana’s hatred, Kahekili orders his execution. In his escape from his attackers, Ka’iana crosses paths with Kaʻahumanu (Luciane Buchanan), whose chief father (Moses Goods) is forcing her, against her will, to marry Kamehameha (Kaina Makua), the son of Hawai’i’s dying king.

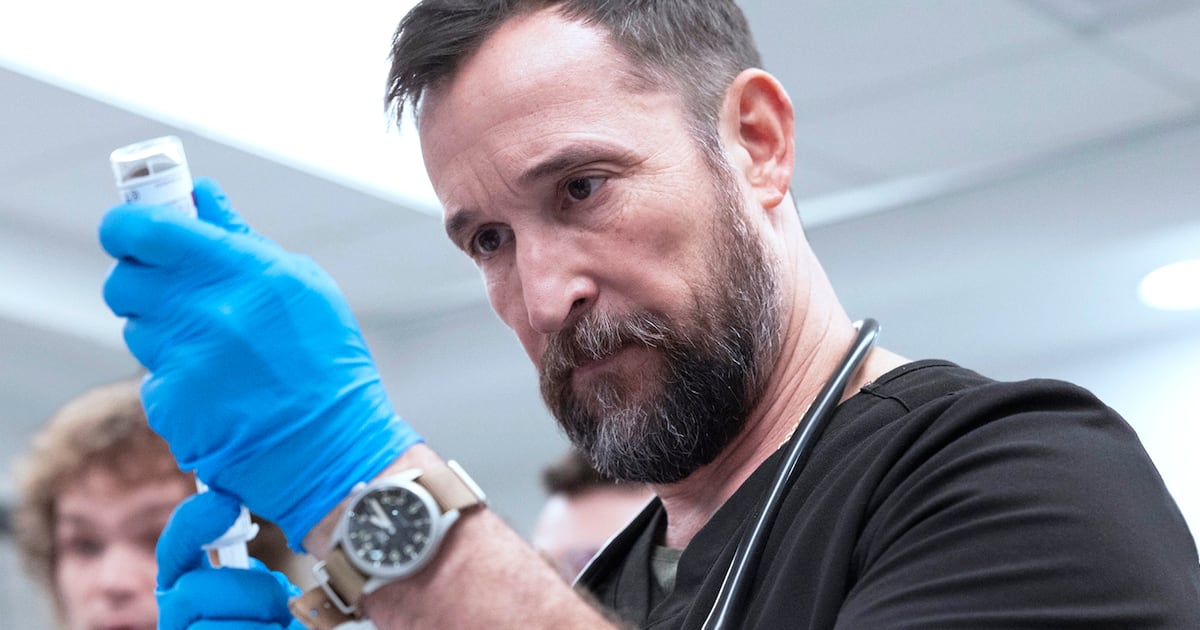

Kaʻahumanu nurses a wounded Ka’iana back to health and, following a run-in with “paleskin” Englishmen who’ve come ashore, sneaks Momoa’s warrior onto one of their ships. So begins Ka’iana’s time at the Spanish port of Zamboanga, where he spends a year learning their foreign language and ways—a process that additionally occurs back in Hawai’i, thanks to stranded Englishman John Young (Benjamin Hoetjes).

This allows Chief of War to segue from subtitled Hawaiian dialogue to English and to introduce modern weapons into the drama’s combustible mix, as Ka’iana smuggles guns back to his homeland to aid in the fight against Kahekili.

Chief of War establishes its central Ka’iana-Kahekili discord and then somewhat sidelines it to focus on the tensions brewing in Hawai’i between Kamehameha and Keōua (Cliff Curtis), the latter of whom is furious because his dad left him in charge of the political kingdom but gave God of War duties to Kamehameha. Keōua’s desire to destroy Kamehameha, and Kamehameha’s attempts to fashion a just and peaceful kingdom (including passing a decree that outlaws murder except in self-defense), takes up much of the action, which is elevated by striking panoramas of its island settings.

Alas, those vistas are sporadically undercut by clunky CGI green-screen effects; if nothing else, the series demonstrates the primacy of on-location shooting. It’s also rife with fascinating cultural and ceremonial details that lend the material its lived-in richness.

Clashes between European and island traditions and values color Chief of War, as do interpersonal strains between Ka’iana and his clan, Kaʻahumanu and Kamehameha, and Kahekili and Kūpule. Friction inevitably begets violence, and Sibbett and Momoa orchestrate a considerable amount of nasty cruelty, with one set piece after another featuring evil deeds and gory kills.

Momoa is often at the center of the mayhem, and he makes for a compelling protagonist—except that the longer the series progresses, the more his perpetual grimacing and glaring turns Ka’iana one-note. A similar fate befalls many of his cohorts, who have stock narrative arcs or, in the case of Makua’s Kamehameha, are envisioned as bland, unconvincing archetypes rather than actual people.

Like every other modern streaming enterprise, Chief of War could be more concisely plotted and there are times when its adherence to storytelling formula dilutes its impact. Sibbett and Momoa’s knowledge of their material and milieu results in an authenticity that counterbalances its conventionality. What they can’t quite overcome, however, is mounting monotony, which climaxes with a finale that spends half its time crawling through set-up before arriving at its main-course melee.

Momoa’s performance is an extension of this shortcoming, becoming less interesting as the tale unfolds. Instead of providing Ka’iana with genuine moral conflict, it renders him a noble, fuming do-gooder who’s always right (and on the side of right, as with James Udom’s Black Englishman Tony) and unbeatable on the battlefield.

Chief of War goes overboard with a conclusion that’s heavy on the hellishness, after which it plants the seeds for a subsequent season. Should that materialize, let’s hope Momoa gives himself more to do than just seethe.