One admitted to kidnapping and ransoming hostages in the Ivory Coast. Others said they had molested children or committed rape. And one, as he prepared for survival in a post-apocalyptic world, contemplated assassinating President Barack Obama.

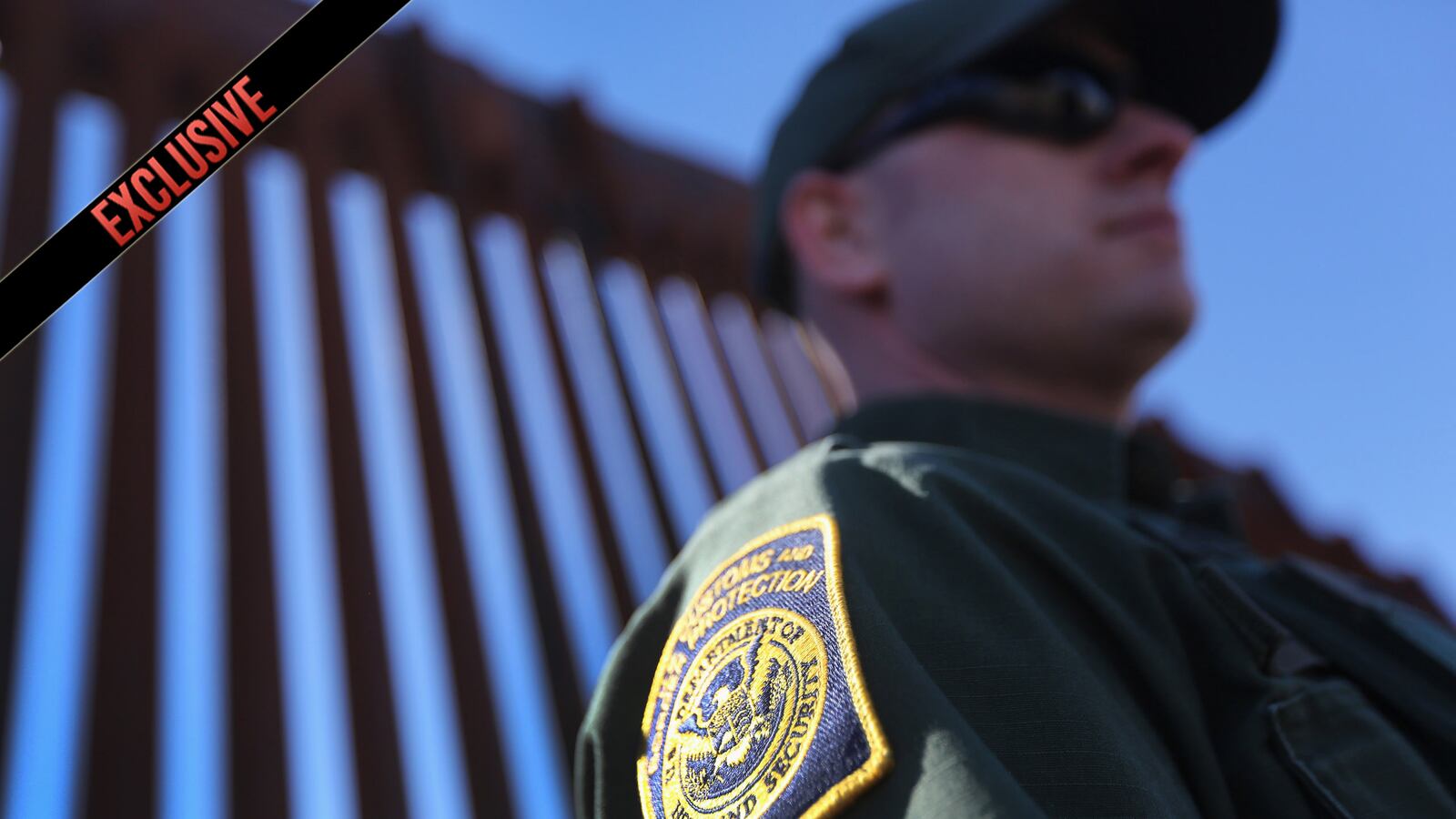

These are among the thousands of applicants who have sought sensitive law enforcement jobs in recent years with the U.S. Border Patrol and its parent agency, Customs and Border Protection.

In many cases, these people made it all the way through the hiring process until one of the last steps—a polygraph exam. Once sitting with a polygraph examiner, they admitted to a host of astonishing crimes, according to documents obtained by the Center for Investigative Reporting.

The records—official summaries of more than 200 polygraph admissions—raise alarms about the thousands of employees Customs and Border Protection has hired over the past six years before it began mandatory polygraph tests for all applicants six months ago. The mandatory polygraph program comes at the tail end of a massive hiring surge that began in 2006 and eventually added 17,000 employees, helping to make the agency the largest law enforcement operation in the country.

Although thousands of applicants have undergone polygraphs, thousands more have been hired without the screening.

The admissions open a disturbing window into some of the people who apply for jobs in law enforcement and cast doubt on the bureau’s internal controls ahead of a possible immigration law overhaul that could call for more border officers.

And they spur the question: Why would anyone share their deepest, darkest secrets for a job?

“You ought to know up front that you’re not going to get the job if you’ve murdered someone. In fact, you might get prosecuted,” said Barry Cushman, president of the American Polygraph Association. “Good people do stupid things sometimes. Very bad things. And it eats away at them.”

The 200-plus “significant admissions” described in the summary reports paint a small yet troubling portrait of some of the kinds of people who have applied to be Border Patrol agents and customs officers since 2008. They also highlight potential weaknesses in the costly hiring process that failed to screen out questionable applicants earlier.

In one case from February, Jose Ramirez, 25, admitted during a polygraph exam that he was the driver in a 2009 single-car crash that killed someone. He previously told investigators in Yuma, Ariz., that the dead passenger was the driver, according to the Yuma County Sheriff’s Office. Ramirez now faces second-degree murder and other charges.

One applicant admitted to smoking marijuana 20,000 times in a 10-year-period. Another was more bizarre: “Applicant had no independent recollection of the events that resulted in a blood-doused kitchen and was uncertain if he committed any crime during his three-hour black out,” according to the Customs and Border Protection summary.

In another example, a woman seeking a job with the bureau told an examiner that she smuggled marijuana into the country – typically by taping 10 pounds of the drug to her body—about 800 times. Scores more admitted that they had engaged in or had relatives involved in human smuggling or drug running. Some said they harbored immigrants not authorized to be in the U.S. or had family members living in the country illegally.

The summaries disclose dozens of attempts to infiltrate the Border Patrol, including 10 applicants believed to have links to organized crime who had received sophisticated training on how to defeat the polygraph exam, according to Customs and Border Protection.

The agency declined multiple interview requests about its polygraph program. In a written statement, spokesman Michael J. Friel said the bureau has a rigorous application process, which includes an initial screening, a background investigation of prospective employees, and the polygraph exam.

“Our commitment to integrity begins at the time of application for employment with CBP and continues throughout the careers of our employees,” Friel said in a statement.

The agency said since it began administering polygraphs in 2008, more than 15,000 people have taken the test, and 60 percent were not cleared. It took almost five years, however, for Customs and Border Protection to require all applicants to take a polygraph. In that time, the agency continued to hire potentially flawed candidates.

The number of employees busted for corruption and misconduct is a fraction of the more than 60,000 employed by the bureau. But misconduct allegations have been on the rise, including a 62 percent jump from 2006 to 2011, according to a recent Government Accountability Office report.

Surprising admissions

Whether a more robust background probe would have discovered the hidden menace on Joseph “Joey” Montross’s home computer will never be known. But a polygraph examiner learned about it just a few weeks after the bureau started the program.

A combat-tested Marine with a security clearance, Montross, then 28, seemed like an ideal candidate. He showed up for a “one-stop” hiring fair hosted by Customs and Border Protection in Dallas in February 2008.

The polygraph exam “was his last hurdle,” John Floyd, Montross’s attorney, said in an interview. “He had passed all the other phases.”

When asked whether he had ever viewed illegal pornography, Montross confessed that he possessed a large amount of child pornography, Floyd said. Montross consented to a search of the Houston home he shared with his parents and three younger half-siblings, according to his plea agreement.

Investigators later found more than 9,000 images and videos of child pornography, the court record shows. He also admitted to producing child pornography. Montross was sentenced to 30 years in federal prison and a lifetime of supervised release.

“He felt he needed to get this off his chest, and it came straight out,” Floyd said of Montross, who confessed again after his arrest. “There is a burning guilt and a compulsion to get it out.”

Montross wasn’t the only veteran who made shocking admissions. Several divulged that they possessed classified information. One said that while in the Army, he “shot and killed an injured Iraqi insurgent; beat an Iraqi during an interrogation and said he kidnapped a child to assist in locating insurgents,” according to the summary produced by Customs and Border Protection.

Other people admitted they had sought out a contract killer or took money to kill someone. Another applicant “affirmed that his infant son died … as a result of child abuse,” reads one heavily redacted example.

Christine Gaugler, who retired in 2011 as Customs and Border Protection’s assistant commissioner for human resources management, said a person could pass the polygraph but still admit things that would make him or her unsuitable for employment.

“I know it sounds crazy that people like that would apply for federal employment, but they’re out of work,” she said. “When you have 60,000 employees, you’re just like a city. Just like a city of that size, you have people who have problems, make mistakes and break laws.”

Social persuasion tools

Psychologists say interrogative techniques used by polygraph examiners are powerful social persuasion tools that can manipulate applicants to unveil their secrets, even if it goes against the person’s self-interest.

“The polygraph examiner is going to tell them that lying is worse than confessing. That’s not necessary true, but that’s what they say,” said Charles Honts, a Boise State University psychology professor and polygrapher. “They tell people: ‘We know people aren’t perfect. People make mistakes. But you won’t get the job if you lie.’ Minimization and justification—it’s standard interrogation technique.”

He added, “Get a nice soft-sell pitch at the beginning and it’s amazing what people will tell you.”

Polygraphers typically spend hours on the exam, building rapport with applicants. They ask a range of questions that are innocuous at first then become more threatening. After the exam, they often invite applicants to unload any mental burdens they might be carrying.

Cushman, the polygraph association president, said it’s easier for an applicant to lie when at home alone filling out an application than it is sitting before a trained interviewer.

“It is harder for someone to lie when the stakes are higher and with a piece of equipment five feet way. And the polygraphers raise the stakes by telling them, ‘I’m good, and I’m going to catch you,’ ” if the applicant lies.

Customs and Border Protection generally refers confessions to outside investigators when there’s ample evidence, including, if possible, a written confession. The polygraph exams are recorded, and applicants sign a consent form that allows admissions to be shared with other law enforcement agencies.

The customs agency has not made public how many cases have been forwarded for further investigation or prosecution or how many have led to convictions.

Confessions don’t always lead to prosecutions or convictions, however. Some applicants who confess to or admit they know about crimes might become informants, or a prosecutor ultimately might choose to not pursue a case.

That happened last year to Cody Slaughter, a 22-year-old applicant from Somerton, Ariz. In July, the Yuma County sheriff’s office learned from Customs and Border Protection that Slaughter told a polygraph examiner he fondled his best friend’s then-2-year-old sister in 2004 and engaged in bestiality.

When interviewed by a detective, Slaughter admitted to the sexual assault, as well as sexual contact numerous times with his horse, a dog and once with a 4-H pig, according to a police report. Slaughter was arrested on suspicion of sexual contact with a minor and three counts of bestiality.

But the local prosecutor’s office filed a charge of making a false statement to police, then dropped the case in December because of “lack of evidence,” said Roger Nelson, the chief criminal deputy county attorney, who added that Slaughter agreed to counseling.

Slaughter could not be reached for comment.

Just because a person confesses to a crime doesn’t mean a prosecutor can charge him or her. In fact, for only a few offenses can a confession lead to prosecution, said Honts, the psychology professor.

“If a prosecutor can’t find anyone to corroborate the confessions, they can’t charge with conspiracy,” he said. “When there are no witnesses, what do you do with it?”

Regardless of whether a polygraph confession leads to a conviction, the task of hiring the right candidates to protect the nation’s borders has been challenging. And with the bureau on the hook to hire thousands more agents and officers in the coming years, it might not get easier – or more efficient.

“The political pressure to make the border safer does not allow it to be subject to dispassionate research and analysis,” said Judee Burgoon, a University of Arizona professor who researches risk detection. “There’s nothing that is going to be a silver bullet, and you’re never going to completely solve the problem of corruption and efforts to infiltrate the ranks.”

Tracking misconduct

How many unsuitable officers or infiltrators slipped through before the polygraph program was implemented or beat the test is anyone’s guess, though the bureau has tried to address the question.

One internal study on corruption, completed in December 2011, found that corrupt agents had been on the job an average of almost nine years before they were caught.

Since October 2004, more than 150 Customs and Border Protection employees have been charged with or convicted of corruption, such as taking bribes to allow illegal drugs into the country.

Before the hiring surge began in 2006, misconduct arrests for offenses like drunken driving fluctuated. Since then, it’s been steadily on the rise. A total of 2,170 reported incidents of employees arrested occurred between Oct. 1, 2004, and Sept. 30, 2012.

In another internal study, dubbed the “Cleared Shelf Initiative,” Customs and Border Protection’s internal affairs office in 2010 found that 56 percent of applicants considered suitable for hire were disqualified after they were given a polygraph. In most of the roughly 300 cases, the polygraph detected a response to a question that alarmed the polygrapher or the applicant made an unsuitable admission during the exam.

At that point in time, fewer than 20 percent of applicants were asked to take a polygraph exam, usually because of outstanding questions after the background investigation.

In the past decade, Customs and Border Protection has paid more than $350 million to private contractors to conduct background investigations for new and current employees, according to records analyzed by the Center for Investigative Reporting. The polygraph program costs about $3 million a year to implement.

Another internal study, “Test versus No Test,” found in 2010 that employees who had not taken the polygraph exam were more than twice as likely to engage in misconduct, such as stealing government property or drug abuse, than those who took the screening before they were hired.

Concerned that Customs and Border Protection was under siege from infiltrators attempting to take jobs, Congress in 2010 made polygraphs mandatory for all prospective hires seeking law enforcement posts. The bureau then hired and trained scores of polygraphers to meet the law’s mandate that all candidates take a polygraph by January 2013. Customs and Border Protection beat its deadline by a few months, reaching 100 percent of all applicants in October.

In June, the agency began administering the polygraph exam before a full background investigation to cut costs and more aggressively weed out applicants. A background investigation, at about $3,000, costs nearly four times that of an $800 polygraph exam.

Internal affairs officials have considered requiring polygraphs for current employees. But such a move, which would have to be approved by the U.S. Office of Personnel Management, could face stiff resistance from unions that represent the bureau’s frontline employees and some high-ranking officials alike.

“If you were to survey the agents, you’d probably find out a good percentage failed a polygraph elsewhere and they’re doing a good job here,” said Chris Bauder, executive vice president of the National Border Patrol Council, the agents union. “Lots of corruption cases could have been caught if they had gone through a thorough background investigation.”

Tia Ghose contributed to this report. For more, visit the Center for Investigative Reporting. Becker can be reached at abecker@cironline.org or on Twitter @ABeckerCIR.