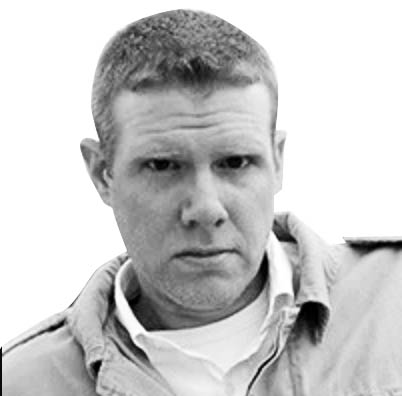

PANAMA CITY, Panama—When MS-13 gang members invaded his home and shot up his family, Bryan Erazo, 23, knew he might be next.

The attack came last August, in the city of Progreso de Yoro, Honduras. Armed men belonging to one of Central America’s most powerful crime groups broke into the home while Erazo himself was at work. The gunmen had come to make an example of Erazo’s mother for failing to pay MS-13’s extortion demands related to her small restaurant. The impuesto de guerra (war tax) charged by the gang can be as much as 40 percent of profits, and often cripples or destroys family-owned businesses.

As the hitmen raised their weapons, Erazo’s grandmother, who had helped raise him from infancy, deliberately stepped into the line of fire in a bid to save her daughter. That act cost her her life. Erazo’s mother was gravely wounded, losing her left eye and the use of her right arm.

“When they come after your people like that, when they kill someone in your family, then they want to make sure there are no loose ends,” Erazo told The Daily Beast. “That way they know nobody will come after them looking for revenge.”

Erazo, who has a wife and a three-year-old daughter, had been working as a taxi driver in Progreso while he studied for his mechanic’s license. Suddenly he found himself on the run.

“Everybody knew me from driving the cab,” he said. “I had to get out or they would’ve killed me just to shut me up.”

So Erazo fled, as have many Hondurans threatened by the powerful and deadly maras, or gangs. According to the Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC), 190,000 people remain displaced by violence in a nation of only 9 million people. And the U.N. Refugee Agency (UNHCR) reports that asylum applications for Hondurans have increased by 1,400 percent since 2011.

Erazo went first to the nearby city of San Pedro Sula, where he worked at odd jobs and saved his money to escape the long reach of MS-13. But in June of this year, when he finally had funds enough for a plane ticket, he decided against seeking refuge in the U.S. A few weeks earlier, Attorney General Jeff Sessions had issued a controversial landmark ruling that unconditionally denies asylum to victims of gang or domestic violence.

Erazo flew to Panama, where he is currently living in limbo, waiting for his asylum application process to run its course. In the meantime, his only option to earn money — since he lacks an official work permit — is on the black market.

Erazo currently works as a mechanic’s assistant earning $15 per day. He sleeps on the floor of a cramped and sweltering apartment that he shares with three other expatriated Hondurans.

“I miss my wife and family. I miss everybody. But I can’t go back,” Erazo said. “If I have to leave here I don’t know what I’m going to do.”

President Donald Trump has vowed he won’t back down from his “zero tolerance” policy for migrants at the border. Although he curtailed the practice of separating children from their families, his plan to detain and criminalize vulnerable immigrants continues apace and the move to categorically turn back refugees seeking asylum might be the cruelest of Trump’s machinations going down at the border.

Sessions’ recent ruling, which has already been put into practice by officials tasked with giving asylum interviews, seeks to make refugee status dependent on persecution by state actors, as opposed to organized crime groups like MS-13.

“The mere fact that a country may have problems effectively policing certain crimes or that certain populations are more likely to be victims of crime, cannot itself establish an asylum claim,” Sessions wrote.

Under the new ruling, many asylum seekers are being declined before they even get to make their case before a judge. Critics say Sessions’ interpretation is in violation of the Constitutionally binding Protocol for the Status of Refugees, which the US and 144 other nations ratified in 1968.

“Sessions’ decision on this undoes, with the stroke of a pen, about 20 years’ jurisprudence about whether gang and domestic-violence victims count as ‘a particular social group,’” singled out for persecution, Adam Isacson, security director for the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), told The Daily Beast.

“We believe that such violence does count, because the lines between armed conflict and criminal violence have become very blurred in the region,” Isacson said.

Many of the immigrants at the U.S. border are fleeing designated “narco states” like Honduras—places where organized crime groups often rival officials’ monopoly on the use of force.

“States are unable or unwilling to protect people from this violence,” Isacson explained. “A threat from a gang with national reach differs little from a threat from an insurgent group with national reach.”

In addition, the fact that Sessions’ ruling also allows case workers to fast-track deportation hearings is a breach of the Constitutionally binding “principal of non-refoulement,” according to Suzanne Nelson-Pollard, a Central America consultant with the Norwegian Refugee Council.

“While the US may have changed its policy regarding asylum claims from gang violence, it still has duties under international human rights and refugee laws to not return any person back to their country of origin where they face persecution, torture or a risk to their life,” Nelson-Pollard said.

Ethical issues aside, the “zero tolerance” policy is already limiting the choices of those like Erazo who are on the run from hired guns. Immigration at the U.S. border fell by almost 20 percent in the wake of Sessions’ ban on asylum seekers and the Trump administration’s generally harsh treatment of migrants since this spring. But that move has only redirected the migrant flow, not dammed the stream.

“Previously, most people went through Mexico, heading for the U.S.,” Nelson-Pollard said. But that trend has changed in recent years.

“Increasingly, people are seeking asylum in Mexico, Belize, Costa Rica and Panama instead of the ever-more restrictive U.S.,” she said.

Panama’s expanding economy, relatively low crime rates, and its status as a “gateway to the north” has made it a popular destination for global immigrants and refugees for decades. Coming from Yemen, Iran, and many other countries, their hope is that they can make their way from Panam up through Central American and Mexico to the U.S. border where they might still meet the Sessions criteria for asylum. As documented in a CBSN report in 2017, thousands of people a year, from all over the world, attempt to cross into the country through the wild and roadless Darien Gap region, which sits on the border with Colombia.

However, as the crisis on the U.S.-Mexico frontier has worsened, there’s also been a spike in immigrants and refugees entering Panama from countries like Honduras and El Salvador. Those nations, along with Guatemala, make up the Northern Triangle of Central America. And they’ve all been hard hit by maras like MS-13 and Barrio 18, which act as intermediaries for cartels shipping cocaine and heroin up from South America into Mexico and the U.S.

According to the UNHCR more than 294,000 asylum seekers and refugees from the Northern Triangle were registered globally by the end of 2017. That’s a 58 percent increase from the year before, and 16 times more people than in 2011.

In Panama, the influx of foreigners is being met with pushback. A sharp uptick in U.S.-bound foot traffic through Darien—peaking at more than 25,000 reported migrants in 2016—has soured some sectors of the public on immigration. Detention centers set up to deal with the flood of newcomers have been accused of holding thousands in “concentration camp” conditions. So far this year, the number of forced deportations has almost tripled from the same time frame in 2017.

While most of the controversial detention centers have now been emptied via mass deportations, an estimated 150 migrants remain in captivity. In June, a video surfaced that purported to show a group of Cuban immigrants being violently mistreated by Panamanian troops. (Immigration officials in Panama declined to be interviewed for this story.)

Unlike in the U.S., gang-based violence can still qualify refugees for asylum status in Panama. But the verification process can take up to three years, and applicants are not allowed to work during that time.

“This leaves them in extremely precarious situations, at risk of extreme poverty and exploitation,” Nelson-Pollard said.

Also the kinds of documentation asylum officials look for, such as police or medical reports, can be hard for asylum seekers to obtain due to corruption and lack of infrastructure in the their home countries. Such hurdles and delays cause many applicants to eventually withdraw their requests.

Even for those who have the funds to see the process through, the chances of being turned down for official asylum status remain high in still-developing countries like Panama. For example, from May to January of 2018, Panama’s National Office for Refugee Attention (ONPAR) received 1,905 requests for asylum. To put that number in perspective, Panama has only granted asylum status to 2,479 people over the last 30 years.

Once their application has been denied, for whatever reason, the applicants face arrest, fines, and in many cases expulsion. The high-risk, low-reward nature of this process leads many immigrants to apply for residency instead of asylum. But that’s not so easy either.

“Panama, like many other countries, has a very restrictive migration policy with a very ‘economistic’ approach,” said Jorge Ayala, the director of a church-sponsored shelter for migrants and refugees in Panama City.

“Any person who can prove that they have the means to sustain themselves can achieve temporary and permanent residence,” Ayala said. But since most immigrants come precisely because they are fleeing physical and economic insecurity, and looking for work and a better life in Panama, they lack the funds to qualify.

“If they can’t prove economic sufficiency, then the system discriminates against them,”Ayala said.

And the system could be about to get worse. In June, a new U.S.-Panama joint task force aimed at countering “irregular” migration in Darien was announced, leading to fears that Washington might push the continent’s southernmost nation toward even stricter policies in order to curb the number of foreign nationals trying to reach the U.S. border.

Meanwhile, Panama isn’t the only Latin American country taking a tough stance on migrants. Nicaragua, now the scene of a popular uprising and ferocious repression that may cause many of its own people to flee, has closed its borders to migrants completely. And Costa Rica has imposed tight limits, shutting the border down if set quotas are exceeded. Mexico’s southern border with Guatemala has become a de facto militarized zone, largely at Washington’s behest, in order to serve as a buffer against Northern Triangle emigration to the U.S.

“The welcome mat isn’t out for Central Americans because they tend to be poorer than the largely middle-class professionals who fled government persecution in the past,” said Isacson. “There is no foreseeable end to the flow,” he added, “because economies are struggling, with few available jobs.”

Shelter director Ayala said that a new “comprehensive and humane” strategy is required to ease migrant suffering in his country.

Refugees are driven out of their own countries by “situations of social and political conflict” and those factors ought to be recognized, he said.

“In Panama, there are no [government] programs that assist immigrants,” said Ayala, who advocates alternatives “so that they can work and live with dignity, while contributing to the development of our country.”

Making a contribution to the the development of the country he hopes will eventually become his permanent home, while also sending money back to his surviving loved ones in Progreso, would be a dream come true for Bryan Erazo.

“All I want is to find good work, support my family, and live here in peace,” he said. “None of that’s possible now in Honduras.”