HAVANA, CUBA — Perusing the drab shop fronts in Havana, resplendent with fly-blown posters of Che Guevara, Camilo Cienfuegos and other “heroes of the revolution,” I alighted on the self-evident problem with communism: Communist economies produce not what the worker needs but what a government bureaucrat has decided to make available for purchase.

The last time I visited Cuba, in 2010, the country was supposedly on the cusp of great change (at least if you were listening to the regime’s apologists in the Western media). Yet five years later and the “reforming” Cuba of Raul Castro looks almost identical to the country ruled despotically for almost half a century by his older brother. The Soviet-style shortages persist, listless youth continue to mope everywhere on street corners and the octopus-like tentacles of the state still reach into every corner of Cuban life.

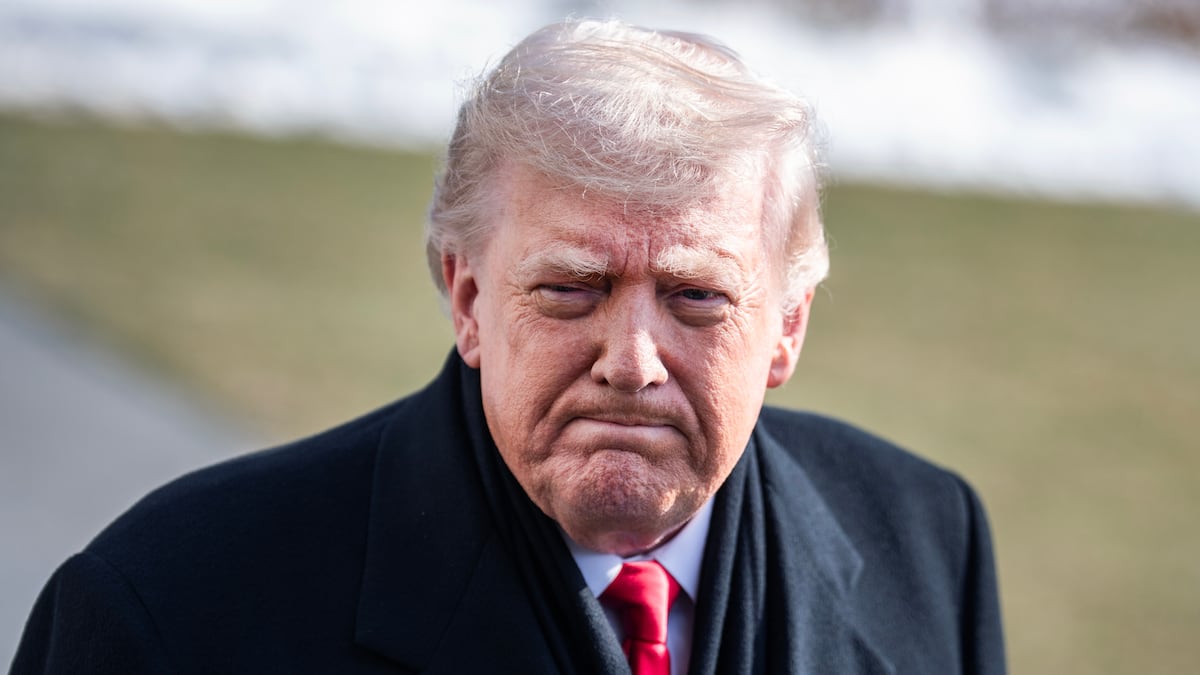

What has changed is the attitude of the White House towards the communist regime in Havana. Together with détente with Iran, Barack Obama appears to view his “legacy” as bound up with a normalization of relations with one of the world’s last Stalinist dictatorships. And so today Cuba will officially reopen its embassy in Washington after 54 years of hostility; an American embassy will reopen in Havana when Secretary of State John Kerry travels there later this summer. Obama has also urged Congress to take steps to do away with the 53-year-old economic embargo which technically prevents Americans from doing business with or traveling to Cuba.

Yet despite the increasingly cordial relationship between Raul Castro and Obama, the supposed changes in Cuba are almost entirely cosmetic. Indeed, on the streets of Havana the only discernible sign of transformation is the increasingly visible presence of a small but newly minted petit-bourgeoisie, tolerated by the Castro regime because (for the moment at least) it is unwilling to challenge the Stalinist center. Apart from this (though you wouldn’t know it from listening to White House press conferences) Cuba remains, as the revolutionary-turned-dissident Carlos Franqui once put it, “a world where the people are forced to work and to endure permanent rationing and scarcity, where they have neither rights nor freedoms.”

In Havana I caught up with one of today’s left-wing dissidents, Pedro Campos. He told me that, contrary to the “reform” and “change” gloss put on matters by the U.S. government, “repression inside the country has not diminished—it’s simply more sophisticated.” According to Campos, “Imprisonments are more frequent but less time is spent inside. For ordinary people, things go on almost as before, especially for those living in the interior of the island and in the east.”

Whereas under Fidel the state would incarcerate critics for long periods with little provocation, under Raul a Cuban is more likely to be hauled in by the authorities for just a few days. It is on being released, however, that the real fun begins, with the secret police rigging up cameras outside the homes of critics and inciting mobs to vandalize property and smear dissidents as traitors. An improvement on the past perhaps, but only in the sense that a broken arm is an improvement on a broken leg.

Not that you would know much of this from reading what passes for commentary on Cuba in the liberal press, where readers are regularly urged to visit Cuba before the American hoards travel there and spoil its “authenticity.” Most bizarre in this respect is the rehabilitation of Raul Castro in the West as a moderate and pragmatic reformer. According to Fidel’s former chief bodyguard, Juan Reinaldo Sanchez, the image of Raul as an affable and approachable family man is “nothing more than a façade. Politically he was a hard-liner focused on repression; since he has succeeded his brother as head of state, police brutalities have not decreased—far from it, contrary to the notion the government has cleverly managed to instill in world public opinion.”

Raul certainly has more blood on his hands historically than Fidel. Increasingly pictured grinning like a slice of watermelon next to the President of the United States, the younger Castro is a capricious Stalinist who in 1959 had hundreds of men summarily executed and thrown into mass graves in eastern Cuba. Narrow-minded and ideologically rigid, older Cubans refer to the feline-like Raul as el casquito, or the “little helmet,” due to his predilection for war and summary executions.

Under the tutelage of Raul, far from being in the grip of glasnost and perestroika, Havana is seeking a rapprochement with the United States only to save its moribund economy. Anyone with an interest in Cuba has heard of the so-called “Special Period” of economic hardship during the early 1990s, when the Soviet Union collapsed and the generous subsidies Cuba’s Soviet benefactor had showered on the country disappeared overnight. Fewer people are aware of the existential crisis faced by the regime in 2009, when according to U.S. diplomatic cables released by Wikileaks, the Cuban economy was three years away from complete collapse.

By that point the global financial crisis and three successive hurricanes had undone the tentative recovery the Cuban economy had undergone since the Special Period; by 2009 Cuba’s balance of trade deficit had ballooned to a staggering 7.9 billion Euros. More recently the slow collapse of the Chavez/Maduro regime in Venezuela, which supplies Cuba with 200,000 barrels per day of cheap oil, has further concentrated minds in Havana.

Obama could be right: The best way to undermine the Castro brothers may be to take away their ideological crutch by ending the embargo and allowing affluent Americans to travel to Cuba as a living demonstration of what the Cuban people are missing. But progressives—and Obama is the consummate progressive—are mistaken if they think Havana will meet America half way on anything relating to democracy or human rights.

Havana is “opening up” because it wants hard currency and access to markets; the only ideology underpinning the Cuban revolution these days is self-preservation and replication, and for that the regime needs an injection of cash. This means that, as in the past, the Castro regime appears to be visibly loosening the screws; however, it is doing so with a wrench firmly in hand, ready to tighten them again once the economic storm has passed.