On June 25, 1894, the French President Marie François Sadi Carnot attended a banquet at the Chamber of Commerce in Lyon. Crowds lined the roads as he went in, and were still there after 9 p.m. when his carriage drew up to collect him. One man present, Sante Geronimo Caserio, had studied the president’s itinerary and was blending into the throng, rolled-up newspaper under his arm. Moving so quickly Carnot’s guards couldn’t stop him, Caserio darted out of the crowd, out of anonymity, and slipped past the police. Dropping the newspaper, he revealed a dagger, which he plunged deep into Carnot’s back. The president dropped, sinking into his seat, and the carriage set off in search of the best doctors in Lyon, while the unrepentant anarchist was apprehended.

Stab wounds were treated at the time by identifying and ligating severed blood vessels, tying a suture around them to stop the bleeding. The assassin had severed the president’s portal vein, however—the vessel bringing blood from the intestines to the liver—and the panicked surgeons were helpless. With his esteemed colleague, Anton Poncet, Louis Xavier Édouard Léopold Ollier studied the wound and decided to apply an iodine bandage to it, hoping for the best.

In the riotous aftermath of the president’s death, Italian-owned businesses were ransacked and demolished. Mobs gathered to burn down the Italian consulate, too, but were stopped by soldiers and police. The surgical trainee Alexis Carrel was, like his fellow countrymen, appalled by the assassination, but he directed his ire not towards things Italian, rather the impotence of his profession. Carrel believed that, if only Carnot’s doctors had possessed the skill, they’d have been able to save the president’s life.

In 1901, the same year Karl Landsteiner devised the ABO blood-typing system, Carrel got space in a lab with access to surgical equipment and dogs. He soon found that, even with recent advances in surgery, the thread surgeons used was too thick for tiny blood vessels, which would easily tear. The needles were too bulky, too, especially around the eye, which, as well as causing extra damage, also caused blood to clot around it, putting the delicate veins and arteries in even more danger. If he was going to attempt to sew vessels together, he would need better. With nothing very delicate available at surgical suppliers of the time, Carrel turned to Lyon’s famous embroiderers. Thanks to his family connections—his mother owned textile factories—he had good contacts in this area. It was in a local haberdashery he found finer, thinner, ‘No. 13 Kirby’ needles from Birmingham, UK, and ‘Coton d’Alsace, No. 500’ for his thread. To help needle and thread slip easily through the vessels, he coated both in paraffin jelly.

Carrel went to embroiderers not only to get his needle and thread but also for the technique. Vessels repaired using existing techniques tended to become infected. If a patient was lucky enough to escape infection, their aging repair would sometimes bulge and eventually rupture. It was clear Carrel needed to devise a new way of repairing blood vessels, one that took into account their special material qualities. With his mother’s tuition, he’d had a head start, and he used his contacts to secure lessons in Lyon’s famous textile district, Croix Rousse, known locally as ‘the hill that works’.

Marie-Anne Leroudier

Wikimedia CommonsThe woman he went to see was called Marie-Anne Leroudier, one of Lyon’s finest embroiderers. Leroudier isn’t always mentioned in Carrel’s biographies. Even those who do name her tend to move on to something else by the end of the paragraph, dismissing her as a ‘seamstress’ whom he happened to ‘see’ and ‘be inspired’ by. But if you take the trouble to look up her work, it’s unfathomably intricate. She produced chasubles and fabric crosses with devotional scenes and embroidered the gold thread that dresses the curtains at the opera house in Paris. She won the gold medal at the 1885 World Fair in Amsterdam and exhibited some ornamented panels in the ‘Woman’s Building’ at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

An embroiderer of such a calibre is an unusual teacher for a surgeon to seek. Most surgeons at the time learned to sew from their mothers, sisters and wives. But a surgeon doesn’t need to depict the Last Supper in thread inside a patient’s body, so what exactly did she teach him that he couldn’t get from anywhere else? Fleur Oakes, formerly the Embroiderer in Residence at the vascular surgery department at St Mary’s Hospital in London, explains what Leroudier would have been able to impart to Carrel—knowledge that he wouldn’t have been able to pick up elsewhere. This ranged from what she called ‘thread management’ (making the thread go where you want it to go) to ways of working one-handed and ways of achieving the intricacy required to work on tiny structures like veins and arteries.

Thanks to Leroudier’s invaluable tuition, he also learned how to pierce only part of the blood vessel’s wall, minimizing the chance of blood clotting around the suture.

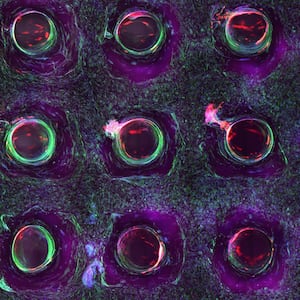

In 1902 he presented his technique at scientific meetings in Lyon and published a paper on his findings. Being able to sew blood vessels together in the way Carrel described would revolutionize trauma surgery. Had his technique been available when the anarchist assassin slashed president Car- not’s portal vein, the surgeons attending him would have been able to at least make a good attempt at saving his life (though a wound such as his would still be considered a challenge today). And at the end of his paper, he shared the news that he was using the technique to transplant thyroid, kidney and pancreas, but those experiments were ‘not sufficiently advanced to enable us to draw any conclusions’.

Carrel would later go on to modify the technique further and it became the basis for much of vascular surgery, including bypass surgery. Vascular anastomosis—sewing together blood vessels—is the reason that people now see Alexis Carrel as the ‘father’ not only of vascular surgery, but also of trans- plant surgery itself. He’s therefore the first person mentioned in any historian’s timeline of organ transplantation, name-checked in introduction after introduction.

Transplants existed for centuries before Carrel, of course, but it was the application of techniques from embroidery—and particularly the uncredited Marie-Anne Leroudier—that made the internal organs no longer off limits to aspiring transplant surgeons.

From the book SPARE PARTS by Paul Craddock. Copyright (C) 2022 by Paul Craddock. Reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Publishing Group.