It has been more than 60 years since Ernest Hemingway was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature and 90 years since the appearance of his breakthrough collection of short stories, In Our Time. Yet, in all that time there has been no major museum exhibition devoted to Hemingway and his work.

Now all that has changed with the new landmark show, “Ernest Hemingway: Between Two Wars,” that the Morgan Library and Museum in New York has organized in partnership with the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum in Boston.

The exhibition, which opened at the Morgan on September 25 and remains there until January 31, is far more expansive than its title indicates. It starts with Hemingway as a high school student in Oak Park, Illinois, and continues past his World War II years.

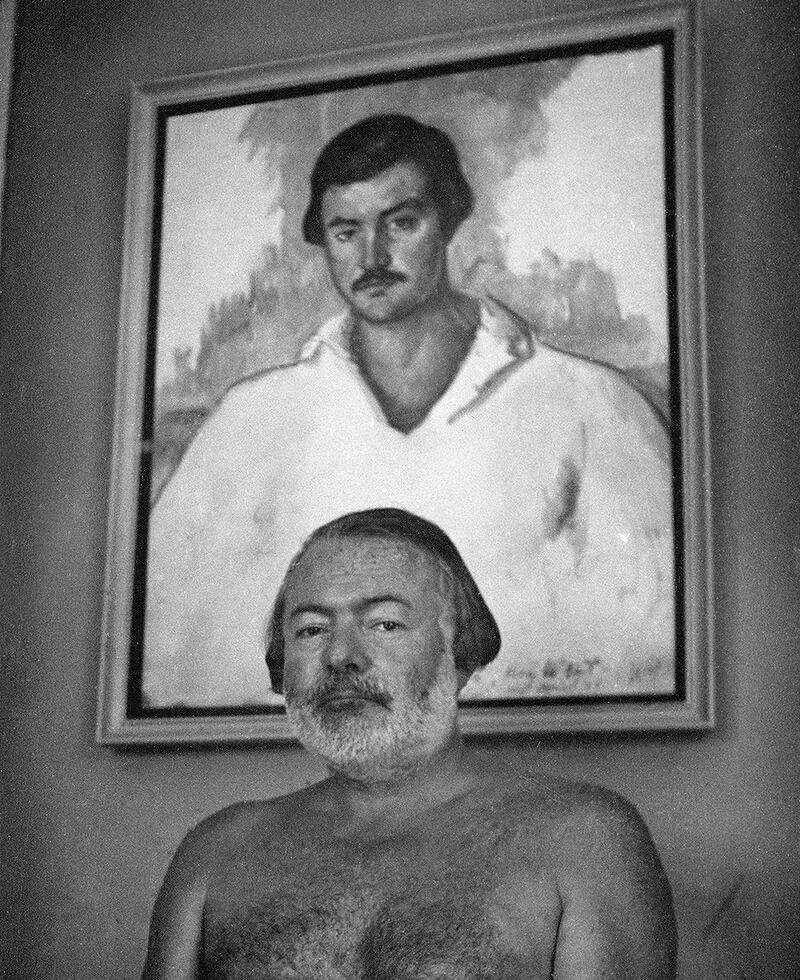

Housed in the West Gallery of the Morgan, the exhibition makes use of a broad range of Hemingway material, from letters to typescripts to notebook entries, and even includes a 1929 oil painting of Hemingway by his friend Waldo Pierce, a fellow volunteer ambulance driver in Italy during World War I.

On the morning I saw “Ernest Hemingway: Between Two Wars,” the crowd was sparse, which is just what is needed for going through the exhibit slowly and taking the time to read Hemingway’s longhand notes as well as his typed letters.

“I felt that the Hemingway myth, or at least the popular perception of Hemingway, had come to overshadow and obscure the prose,” Declan Kiely, the show’s curator as well as the head of the Morgan’s literary and historical manuscripts, has said.

To capture the Hemingway who isn’t the prisoner of the Hemingway myth, Kiely and the Morgan have organized “Ernest Hemingway: Between Two Wars” chronologically in six sections:

In Section 1—The Class Prophet, we see Hemingway writing with remarkable maturity in his high school literary magazine, Tabula. In Section 2—World War I, we are reminded that it was only a little over a month after he took up his duties as a volunteer ambulance driver in Italy that Hemingway was wounded and spared further risk.

In Section 3—Paris, we watch Hemingway transform himself from a journalist to a novelist and along the way develop friendships with Ezra Pound, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and James Joyce. In Section 4—Key West and Havana, we see a now-famous Hemingway go lion hunting in Africa, then return to Europe to write about the Spanish Civil War.

In Section 5—World War II, Hemingway, now in his forties, resumes doing war reportage, and in Section 6—An Old Hunter Talking with Gods, we witness Hemingway struggling with depression while trying to duplicate the achievements that won him acclaim in his middle twenties.

The result is a framework that provides a clear way of looking at Hemingway’s life and at the same time lends itself to Hemingway stereotyping by giving us Hemingway the naïve youth, Hemingway the witness to war, Hemingway the big-game hunter.

Fortunately, the exhibit is far better than its conventional organization. The materials on display—most for the first time—give a palpable richness to Hemingway’s life that even the most picture-laden biography could not provide.

When we see Hemingway in high school, then soon after in his Red Cross uniform in Italy, we realize how much courage it took for him to go out into the world on his own rather than head off for college. When we see Hemingway prize a not-especially-good picture of himself because it is by his friend Waldo Pierce, we realize what a sentimentalist he could be. When we see the many endings Hemingway tried out before he settled on the one he finally used for A Farewell to Arms, we realize that he constantly struggled to maintain the terse style of writing that was his hallmark.

This richness of material culminates with the final item of the exhibition—a letter J.D. Salinger, at the time a sergeant in the Army’s Counter Intelligence Corps, wrote to Hemingway at the end of World War II. The two had met during the war, and Salinger’s letter reflects his trust of Hemingway, his willingness to open up to him.

In his letter Salinger confesses that he has checked himself into a hospital in Nuremberg because, as he puts it, “I thought it would be good to talk to somebody sane.” Then after a series of flattering remarks and jokes, he tells Hemingway, “The talks I had with you were the only hopeful minutes of the whole business.”

The letter says much about Salinger’s war-weary state of mind, but it is also a poignant reminder of Hemingway’s compassion, a side of him that all too often has not gotten the attention it deserves, despite being central to his life and work from the ’30s on. “Ernest Hemingway: Between Two Wars” invites us to see this side of Hemingway, and when we look for it, the compassion emerges in unambiguous fashion.

In his 1937 novel, To Have and Have Not, Hemingway’s central character, Harry Morgan, the struggling owner of a small cabin cruiser, often sounds like a character straight out of John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, insisting that “a man alone ain’t got no bloody fucking chance.”

Five years later in the introduction to his 1942 anthology, Men at War, Hemingway puts his heart on his sleeve, with his admission, “This introduction is written by a man, who, having three sons to whom he is responsible in some ways for having brought them into this unspeakably balled-up world, does not feel in any way detached or impersonal about the entire present mess we live in.”

And later, in World War II, the compassionate side of Hemingway comes out in his battlefield reportage. To be sure, Hemingway did his share of drinking and carousing while covering the war for Collier’s, but he also captured the terror experienced by the men he reported on by sharing their dangers.

In his famous account of the D-Day landing, “Voyage to Victory,” Hemingway’s ego is on display, but as he heads toward the Fox Green sector of Omaha Beach on a small landing craft with the troops who will go ashore, he is risking his own life as he records their and his anxiety in the face of the heavy fire coming from German shore batteries.

For most other writers, a war story like “Voyage to Victory” would have been the high point of their careers. For Hemingway, the story, with its focus on doing your job while facing your fears, was, as the Morgan’s exhibition reminds us, just one more episode in a life rich with intensely felt, brilliantly described episodes.

Nicolaus Mills is professor of American studies at Sarah Lawrence College. He is currently at work on a book about Ernest Hemingway and his World War II circle.