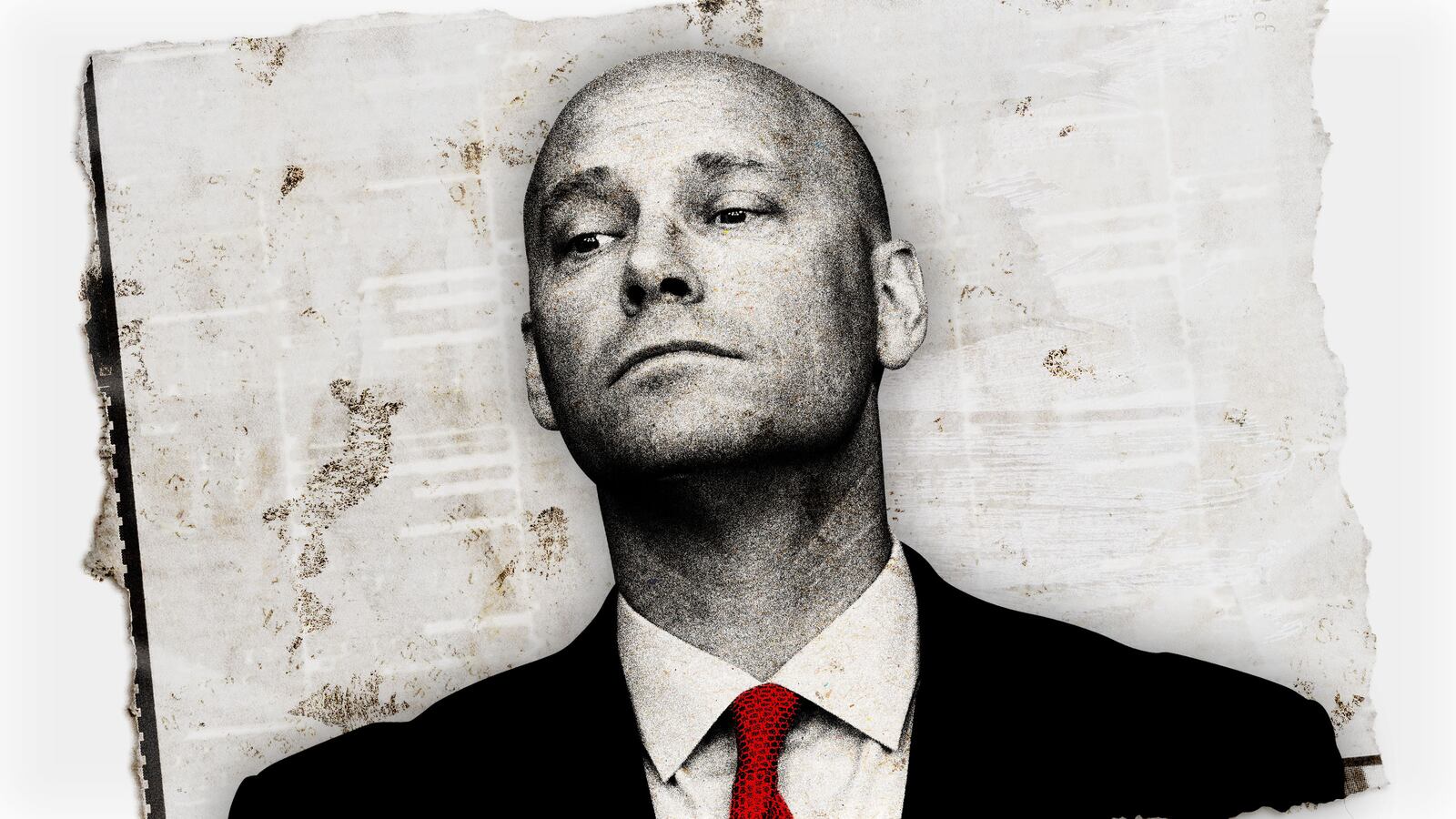

Vice President Mike Pence’s incoming chief of staff Marc Short disparaged people living with HIV and AIDS and claimed that the transmission of the disease was largely the result of “repugnant” homosexual intercourse in an early ’90s column for his college newspaper.

Writing in a conservative publication at Washington & Lee University, Short criticized what he called “the propaganda campaign ignited by gay activists and carelessly perpetuated by journalists whose intent is to scare all heterosexuals into believing they are prime targets for contraction of the disease.”

“The campaign's purpose,” Short wrote, “is both to lobby Congress for more federal funding of AIDS research and to destigmatize the perverted lifestyles homosexuals pursue.”

Short even suggested that the gay community was pleased to see NBA Star Magic Johnson’s HIV diagnosis because the highly publicized case would undercut claims that gay people were particularly vulnerable to the virus or responsible for its transmission.

“No one can doubt… the celebration by AIDS activists of Magic's infection,” Short wrote, as it “shocked the world into believing this nonsense that everyone is prone to infection.”

The column was published in The Spectator, a conservative student newspaper that Short co-founded as an undergraduate in 1989. Short served as an editor for the publication until he graduated in 1992.

“I regret using language as an undergraduate college student that was not reflective of the respect I try to show others today,” Short said in a statement to The Daily Beast on Tuesday. “We have all learned a lot about AIDS over the past 30 years and my heart goes out to all the victims of this terrible disease.”

The column, which was surfaced by the Democratic opposition research group American Bridge, provides a window into the early beliefs of one of the Republican Party’s most powerful behind-the-scenes operatives. Short previously served as Donald Trump’s chief congressional liaison and, before that, the president of the Koch Brothers’ political fund.

Its surfacing adds to an ongoing debate over the degree to which those in politics should be held accountable for the writings and actions of their youth—a conversation that’s been fueled, in recent weeks, by revelations that top Democratic leadership in Virginia had been pictured in blackface during their college and medical school years.

And it may return attention to Pence’s own record on gay rights and HIV. As Indiana governor, the future vice president championed a law that allowed business owners to deny services to the LGBT community based on the owner’s religious beliefs, before signing a “fix” to the bill under public pressure. Under Pence’s governorship, Indiana also saw a resurgence of HIV cases that researchers said was due to his reticence to adopt needle exchange programs. He eventually reversed course, issuing an executive order allowing needle exchanges.

The vice president’s office did not issue a comment for this article.

One prominent activist said that the column flagrantly misrepresented the emerging scientific consensus of the early 90s.

“I wrote stuff in college too. And I don’t look back and say, ‘Oh, sorry, it was my college years.’ You’re either on the right side of stuff or the wrong side.” said Peter Staley, a long-term AIDS and gay rights activist. “He was taking classic Jesse Helms-style rhetoric from the late '80s and putting an early '90s spin on it and sounding like the fools they all were… Guys like him wanted us to die. And they had an effect.”

Asked if he was referring to Helms, the infamously bigoted North Carolina senator, or Short, Staley clarified: “Rhetoric like that killed us. Let’s put it that way.”

The impetus for Short’s column—which reflected, to a degree, a lingering obliviousness in the early 1990s about the AIDS crisis paired with suspicion and anger directed at the gay community for it—seemed to be an interview that Edwin Wright, a W&L alumnus, had recently given to the school’s main student newspaper, the Ring-tum Phi, about his own HIV diagnosis. In it, Wright had noted that he’d watched four people die from the symptoms of AIDS, but didn’t find death any easier to deal with while knowing his own was pending. “I know exactly what I'm in for,” he said.

Short, at the time, said he felt “sympathy” for Wright, who was gay, as well as other people with AIDS. But, he added, “that does not mean that we glorify homosexuals' repugnant practices of frequent anal intercourse nor should we consider them brave for coming out of the closet.” Short concluded his column with a warning: “Homosexuals who pursue unhealthy lifestyles and engage in high risk sexual behavior, specifically anal intercourse, may very well end up like Mr. Wright.”

There is no readily-available evidence that Short’s column caused a backlash on campus at the time. Short’s fellow editors on the masthead did not return request for comment.

But The Spectator’s overall editorial product was put together explicitly to serve as a conservative provocation to the campus’ culture. Will Tanner, the publication’s current editor in chief, told The Daily Beast that The Spectator was originally founded in 1989 “to push back against creeping liberalism in the administration and school.”

Some of Short’s other columns for the publication reflected that mission. He wrote in opposition to a Supreme Court decision requiring the Virginia Military Institute to admit women, a landmark 7-1 decision that prompted nationwide gender integration in higher education. In another column, he opposed efforts by a governing body at W&L to recognize the college’s first all-black fraternity on apparent grounds that he felt it would undo the diversity of the other fraternities.

The Spectator’s frequently controversial editorializing elicited a faculty boycott campaign reminiscent of both contemporary campus political controversies and more general efforts to “de-platform” objectionable speakers by going after advertisers.

In 1991, Valerie Hedquist, a visiting art professor at the school, began writing letters to businesses in Lexington, Virginia—where W&L is based—encouraging them to sever ties with The Spectator. It was not immediately clear what content prompted the campaign, and Hedquist did not respond to questions about the ordeal.

“Her actions,” The Spectator wrote in an unsigned editorial, “consist of little more than an attempt to suppress ideas and discourse which she for some reason finds threatening or inappropriate within this liberal arts institution.”