The NYPD was shocked by several things they saw during their morning raid on the building on W. 74th St., but one thing particularly scandalized them: the women inside were wearing tights. The police captain confirmed the sighting to the New-York Tribune, which said that “two of his men saw the tights with their own eyes.”

Their target that May day in 1910 was the yoga school of Pierre A. Bernard. This was not Bernard’s first run-in with the law, nor would it be his last, but it was the one that got the American-born guru and unabashed practitioner of Tantric and hatha yoga in the deepest trouble. It also spelled the beginning of a challenging period for what was then seen by some as an exotic and even dangerous practice.

Yoga was first introduced to the country nearly 20 years earlier, but it was during the early 20th century that it began to attract more interest, particularly among the wealthy and artistic classes. In a response that has become all too common in the country, many in mainstream society decided the foreign-looking downward dogs and cobra poses were a threat, especially to American women. (Let us not forget about the tights!)

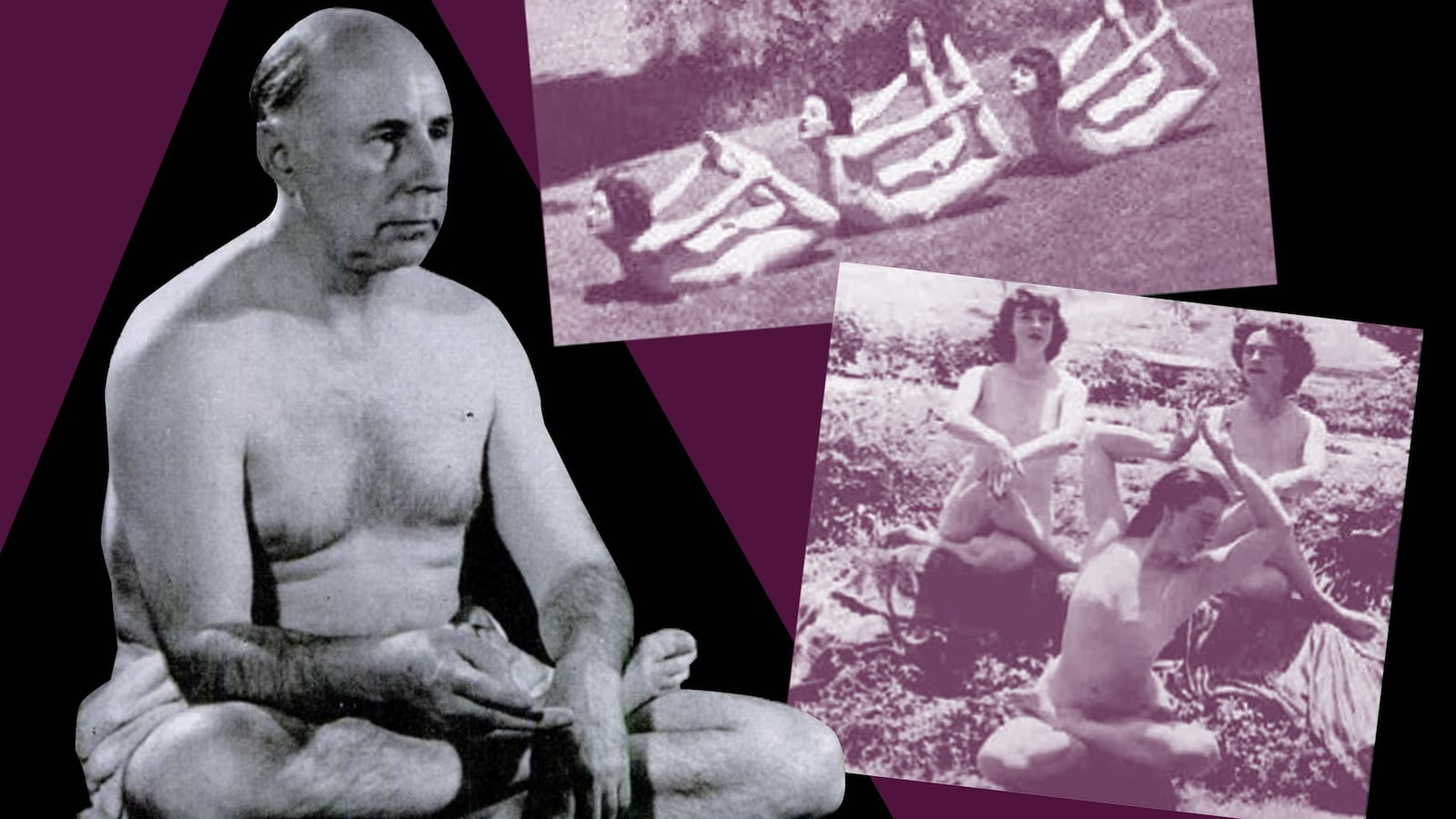

Bernard was one of the country’s most popular gurus at the time, and, though he was white and American, he became a particular target of the racist reaction to yoga’s growing popularity. His personality—bombastic, libertine, exhibitionist—didn’t help allay fears. Charged with kidnapping two young women followers in 1910, the “Omnipotent Oom,” as he became known, spent three months in Sing Sing before the case fell apart. It was just the first in a series of scandals that would hit the American yoga community, but that would fail to take down the great “Oom.”

Bernard was not the yoga teacher’s given name. Born Perry Arnold Baker in Iowa in 1876, his fate was sealed in his early teens when his mother remarried and sent him to live with an uncle in Nebraska. It was there that he met Sylvais Hamati, a Syrian-Indian neighbor who took the young boy under his wing, teaching him everything he knew about hatha and Tantric yoga, meditation, and Vedic philosophy. Bernard was immediately hooked.

When it was time to leave home, the budding yogi set his sights on San Francisco, where he hoped to make a living from his passion. As Stefanie Syman writes in The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America, “through Hamati, Perry had found his calling: he’d bring Tantric yoga to other like-minded or at least open-minded Americans.”

While Bernard had studied the traditional Indian practices with Hamati, he incorporated some outside influences into his own—elements of theosophy (a spiritual practice that was all the rage in the country) and a dose of circus flair for good measure.

He made news in San Francisco in 1898 with a special demonstration called the Kali Mudra that was a bit more sideshow performance than yoga routine. In front of a captivated audience, Bernard used the breathing exercises of his yoga practice to slow down his heart rate and enter a trance-like state. The crowd was in awe when he showed no signs of feeling when his assistant then began to stick needles through his face.

In addition to his performances and overtures to the medical community (Bernard was ahead of his time in his belief that Eastern and Western medicine should both be embraced), he also established a secret society in San Francisco called the Tantrik Order (T.O.). For the rest of his life, he would continue to use exclusive membership and the allure of secrecy as a model for his business.

Despite its cloak-and-dagger nature and some admittedly scandalous practices, the T.O. attracted members of the city’s elite. Men and women interested in joining were required to pay $100 in dues and recite an oath that “pledged ‘unreserved’ compliance, obedience, and resignation to the order’s teachers, and ‘promise[d] perpetual silence to the uninitiated,” according to Syman.

The structure of the organization has echoes of that of scientology—membership was arranged in something of a pyramid, with each successive level of attainment gaining new knowledge and privileges. Sex ceremonies were part of the Tantric rituals for only those in the highest inner circle.

“If the T.O. seems exotic by today’s social standards, it was not very far from the mainstream of American life at the time,” Robert Love writes in The Great Oom, his biography of Bernard. “Every night in cities large and small, bewhiskered fraternal brothers and their sisters in veils scurried across the cobblestones from meeting to meeting, carrying rule books, manuals, pins, badges and feathers.”

The allure of the mystical—including that of yoga—might have been gaining increasing interest from members of high society, but it was also attracting attention of a different sort. In 1908, a New York Times headline announced a scandal involving the wife of Purdue University’s president. She had—gasp—“become a yoga.” Her husband confirmed “a report that his wife has withdrawn from the world, including her husband and family, to pursue a mystic teaching supposed to be imported from India.” It was such a disgraceful turn of affairs that he offered his resignation.

Starting in the late 1880s, nationalist sentiment was beginning to take hold and there was growing concern about immigration to the U.S. From the late 19th century through the early 20th century, a series of acts were passed that specifically targeted Asian immigrants. In addition to the growing anti-Asian racism in the U.S., there was also a growing concern over “white slavery” in the country—the sex-trafficking of young American women.

It was into this swirl of hysteria and discrimination that Bernard landed in New York City around 1910. He set up his new center of operations on the Upper West Side, where he taught his students yoga poses and lectured on the Vedic philosophies, and welcomed the more elite members of his Inner Circle. He also continued to cultivate his bold and brash persona.

His problems began when he got mixed up with two different young women: 19-year-old Gertrude Leo, his sometime-secretary who had followed him from the West Coast, and 18-year-old Zelia Hopp, a local woman with a heart problem whose family had handed her over to Bernard for treatment.

What is known is that both women were studying under Bernard, and that both had also had a sexual relationship with the guru. “Bernard’s Tantra gave him a powerful tool for his own sexual gratification and empowerment,” Syman writes, and the power dynamics were no doubt skewed in Bernard’s favor. But whether he had mistreated the women, as they claimed, is unclear.

The police became involved after Hopp sent a letter to her sister stating that all was not right with her treatment at the hands of Bernard. Hopp’s sister immediately went to the NYPD, who were excited to have an excuse to raid Bernard’s latest school. They barged into his “sumptuously furnished house… while he was instructing a scantily attired class of men and women in ‘mysteries of the Orient.’”

The Grand Jury trial lasted five days and its every move was followed closely around the country. Hopp, Leo, and their families accused the yoga instructor of hypnotizing his charges, of making false promises, of luring them into sexual relationships with him, and of running a cult. While the women said that they “had their liberty at all times,” they also claimed that the hypnotism restricted their full freedom.

Throughout it all, Bernard remained unfazed. The Buffalo Times reported that “he was unruffled when arraigned in court. He smiled in a languid manner during the proceedings and yawned while Miss Hopp was telling her story.”

Perhaps the most entertaining exchange occurred on May 7 when Hopp recounted that the “Oom” had promised to marry her. When she was asked if he had then refused to marry her, she answered “no.” Bernard was then asked “Do you want to marry her now?” He “muttered” that he would, “but Magistrate Breen came to the girl’s relief when he announced that the proposal was too sudden.” With both parties barely escaping a court-arranged marriage, the trial continued.

Juicy details spilled out about membership in the T.O., about the sex rituals, the fees charged, and the oaths of secrecy some members signed in blood. And while all of these details were true for a select number of people, it’s also true that doctors and actors, the wealthy and young women interested in physical fitness were all flocking to Bernard to learn this new theory of movement. According to the Buffalo Times, Bernard “described himself as a physical instructor and teacher of languages.”

The judge said the case was one “which had no parallel in its shameless details,” and Bernard was sent to jail on an enormous $15,000 bail while he awaited an official trial. And there he sat, and sat and sat. Three months later, after both women had left the city and were no longer willing to testify, Bernard’s lawyer convinced the court that, since no trial was forthcoming, they were required to release his client.

In the years that followed, yoga continued to be the subject of scandals, criminal investigations, and fearmongering headlines (“A Hindu Apple for Modern Eve: The Cult of the Yogis Lures Women to Destruction,” read one edition of the Los Angeles Times in 1911). But Bernard refused to be cowed.

The year after his release, the “Omnipotent Oom” was back at it, establishing new operations in New Jersey. Later, he went on to create a community in Nyack, New York, bankrolled by Anne Vanderbilt. The rich, famous, and open-minded flocked to the guru, even while he continued to be dogged by police raids and investigations.

But the harassment and racism against yoga in the early 20th century couldn’t snuff out the inevitable: that the “exotic” practice from the East was destined to dominate America, tights and all.