“There’s all these assholes who, for years, have been going, ‘Oh, you know, Dark Side of the Moon absolutely syncs up with The Wizard of Oz.’ And you know what? No, it fucking doesn’t!”

True to form, Roger Waters, the bassist and primary lyricist of Pink Floyd until the mid-1980s, has a deeply held opinion on that particular urban legend. Still, much like the “Paul is dead” rumors The Beatles had to contend with in the late ’60s, Waters once admitted to me—at a Manhattan recording studio a few years back, after our conversation turned to Dark Side of the Moon—that it’s a badge of honor for his former band’s landmark album to hold such an exalted place in pop culture that it’s birthed such a wild conspiracy theory.

Still, Waters hates to give even an inch: “Even if it does,” he says pointedly, “it’s nothing to do with the music.”

Pink Floyd’s The Dark Side of the Moon, which turns 50 this month, is the granddaddy of all classic rock albums. It’s the best-selling British album ever, and the third best-selling album of all time—behind Michael Jackson’s Thriller and AC/DC’s Back In Black—with sales approaching 60 million copies worldwide, and streaming numbers, across all discernible demographics, to match. It’s also the album that catapulted Pink Floyd—a band that had never sold more than 250,000 copies of any of its previous, psychedelic/prog-tinged albums—into the rock ’n’ roll stratosphere, forever changing the lives of Waters, guitarist David Gilmour, keyboardist Richard Wright, and drummer Nick Mason.

“These days, you have to get into the right mood to listen to a whole album, I guess,” Gilmour mused when we last spoke, a few years back, of Dark Side’s legacy as probably the best and truest concept album. “But there are still lots of people who love to listen to music that way. Listen to a whole thing, a whole piece, all the way through, and get really into the mood of the whole thing, rather than listen to shorter pieces. Dark Side is for them, really.”

With that in mind, Sony Legacy released a gorgeous new box set this week commemorating the album’s 50th birthday. And while it doesn’t include anything truly new, the album—once the go-to LP in high-end HiFi stores to demonstrate what a great stereo system could offer—has never sounded better. Highlights do, however, include an Atmos mix that surpasses any of the previous surround mixes of Dark Side across the years—from the ’74 Quad mix to the ’03 SACD surround mix and more recent 5.1 mix from the excellent Immersion edition released in 2011—as well as a live performance of Dark Side from London’s Wembley Arena during the band’s 1974 tour.

“I think that for any band, but especially for a band our age, the concept of our stuff appealing to a younger audience is the best feedback that you can get,” Mason said when I pointed out the healthy streaming numbers Pink Floyd enjoys to this day. “It’s always important to have some relevance to a younger audience. But ultimately you feel a sense of responsibility, like you don’t want to spoil your reputation by putting something out that you can’t stand by.”

When I asked about the rich, full sound of the surround mixes of Dark Side, Mason explained, “We were certainly students of learning to get the right sounds during our early days at Abbey Road.” He also gave credit to engineer Alan Parsons as well as Chris Thomas, who, like Parsons, had worked with The Beatles and helped in the final stages of production and mixing to get Dark Side across the finish line.

“We worked hard on these,” Andy Jackson, Pink Floyd’s longtime in-house engineer, added. “Ardent fans have heard the 1974 Wembley show. We used a different source and it’s never sounded this good before. We spent ages on it.”

“The sounds they put down were excellent,” he continued. “But something that gets lost a bit, and that I hope the Wembley concert will show, is that Pink Floyd were a great [live] band.”

But perhaps what stands out about Dark Side the most after half a century in the public consciousness is how much soulfulness the band packed into 43 minutes. After years on the album-tour-album treadmill, Mason recalled that it was with “Echoes,” the 23-minute piece on the second side of 1971’s Meddle, where the band finally found a way forward and out of its early psychedelic musings. Without that track, Dark Side might never have happened.

“In the early days, Syd was the frontman and driving force,” Mason recalled of Syd Barrett, who left the band in 1968, a casualty of drug use and untreated mental health issues. “We struggled after that. But with ‘Echoes,’ we found a sound that felt like something new. The whole sort of Dark Side, the structural way it was put together, was completely different to the earlier stuff, with the opportunities to improvise and so on.”

“Without the Beatles, we wouldn’t be here today, because Sgt. Pepper became the first album to outsell singles,” Gilmour added. “From that, it gave a springboard for all those artists from our generation who made albums rather than constantly trying to make hit singles.”

“And, of course, with Dark Side, Roger really stepped up,” Mason said of the man so often seen these days as the villain in the Pink Floyd story—despite him being the one who largely conceptualized the album. “It started with the concept of the pressures of modern life, like travel and money and time and death. Eventually, Roger tied it all together as a meditation on insanity.”

“The ideas were mine. The lyrics were mine,” Waters, true to form, told me flatly.

While technically true, perhaps, Dark Side was also Pink Floyd’s most collaborative time.

“There was no leader,” Alan Parsons told me. “Roger and David worked side by side, egging each other on. And Rick and Nick were crucial; hugely instrumental. There was no ego beyond the occasional disagreement about how to make a particular piece or sound the best that it could be.”

“It’s just something that we did,” Mason concurred. “That magic sort of happened. None of us could quite understand it. And we couldn’t recreate it with different people. When we played together, we created something that we don’t really understand but that works incredibly well.”

Gilmour’s wife, Polly Samson, the author (and sometime Floyd lyricist), had a more bittersweet take on the band’s collaborative spirit.

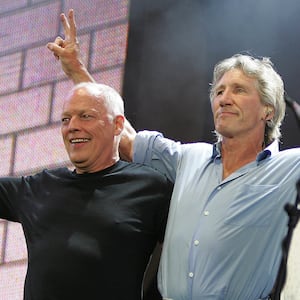

“I remember thinking at [the 2005 benefit concert] Live 8 that there’s nothing more excruciating than being in a room with David, Rick, Nick, and Roger,” she recalled. “It’s awkward. You’re with these four men, they do not speak, there are awkward silences, and the next thing you know they’re up on stage and speaking so eloquently through their instruments. There’s this real divide between this incredible articulacy they have with music that they absolutely don’t have in their relationships. That night at Live 8 it really struck me, that terrible awkwardness.”

As the easygoing go-between in the often cold (though currently hot) war between Waters and Gilmour—which has been raging ever since the mid-1980s split of the classic Pink Floyd lineup—Mason has a more prosaic view of things.

“I look back and most of the time spent was fun, enjoyable,” Mason recalled. “Yes, of course there have been moments where we’ve been in the middle of some sort of punch-up between band members, or things were not going so well. But in general, compared to having a proper job, it was fantastic!”

It was also Dark Side—and its massive, earthshaking popularity—that made the demise of that classic lineup of four very different men almost inevitable.

“We really only broke through in America in ’72, after Dark Side of the Moon,” Gilmour added. “Within three months or so we’d transformed from being a theater band to being an arena band. Even now, I think a lot of Americans see Pink Floyd as something that kicked off with Dark Side because the transition was enormous.”

Still, Gilmour says, he’s proud of Dark Side and loves playing the songs even 50 years later.

“I never tire of playing these songs,” Gilmour said with a smile. “I suppose I should. But I don’t.”

As for Waters?

“As the clock ticks down, I have no interest in revisiting any of the old stuff really, with the possible exception of The Dark Side of the Moon,” he admitted. “I have no interest in touring it, but [director] Sean Evans and I have started to make a film called Swaddle, based around the music from the Dark Side tour from about 10 years ago, and it’s actually really, really good. It’s black and white. We made it very much with black and white in mind.”

And of course, a newly recorded solo version of Dark Side is reportedly coming from Waters in May.

Mason, again, is more circumspect.

“There’s always been a feeling that rock music is meant to be ephemeral, and moves on, and gets lost, and so on,” he told me. “I come from a generation where that’s exactly what it was thought to be: fairly short-lived. And we’re now living in a world where that’s almost like the way we used to go and find all those early R&B artists. But people are discovering Pink Floyd’s music, and there’s still something to be learned from it.”

“I really want more people to discover our early music, and appreciate how unique and special it was,” Mason continued, admitting it was the driving force behind his extensive work on the video that accompanied the remarkable 2016 Pink Floyd box set The Early Years: 1965-1972, as well as the impetus behind his current band, Saucerful of Secrets. “But it’s always about Dark Side and Wish You Were Here and The Wall: the tyranny of the big three, as I like to say. Still, rightly so.”

As for the possibility of a Pink Floyd reunion—which seems far-fetched, given the current state of relations between Waters and Gilmour—Mason says he remains eternally hopeful.

“If a miracle happened and Roger and David suddenly said, ‘Do you know what? We really need to go and do this tour,’ for some worthwhile cause or other, I’d happily do it,” he says. “But I’m certainly not holding my breath.”