At least on paper, Democrats talk tough about the importance of protecting the democratic process from a flood of billionaire bucks. “Big money is drowning out the voices of everyday Americans,” the 2016 Democratic Party Platform reads. “We must have the necessary tools to fight back and safeguard our electoral and political integrity.”

This isn’t a new development; campaign finance reform played a major role in every Democratic presidential platform since 1992. Last month, dual-frontrunners Joe Biden and Elizabeth Warren released their own campaign finance reform proposals. Bernie Sanders put forward a bold plan that would mandate public financing laws for all federal elections.

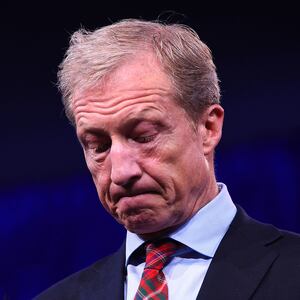

And then there’s Democratic megadonor and billionaire Tom Steyer.

Steyer is most prominent for claiming the title of “single largest donor in American politics” on several occasions. Whether you think that honorific is worthy of praise depends largely on whether or not your name is Tom Steyer.

“I was watching how this campaign was going, and in my opinion, the overriding issue today is that the politics of our country, the government, has been taken over by corporate dollars,” Steyer told The Atlantic’s Edward-Isaac Dovere. Steyer seems to view the corporate capture of American politics more as a challenge than a warning – and it prompted him to launch a quixotic campaign for the presidency.

Steyer’s campaign makes a mockery of Democratic calls for limitations on the corrosive influence of money in politics. It is a campaign devoid of any coherent message beyond ankle-deep platitudes about impeaching Donald Trump and saving the environment. The campaign exists almost entirely on the airwaves, and is bereft of actual donors or ground support.

Yet Steyer will be on the stage at November’s Democratic debate while credible public servants like Secretary Julian Castro will not. Call it the billionaire’s bluff.

Between July 1 and Sept. 30, Steyer spent a staggering $47.6 million of his $1.6 billion fortune to secure a spot on the October debate stage. Despite polling at or below 1 percent nationally since announcing his candidacy, Steyer made clear his plan to loan his campaign at least $60 million more.

Steyer has barely scraped together the 165,000 small-dollar donors required by the Democratic Party to qualify for participation in official debates. That’s thanks in large part to Steyer’s fortune, which enables him to run a sweeping national ad campaign designed to pull donors from every nook and cranny of the republic. And his strategy is (barely) working—but at what ethical cost?

A growing list of Democratic Senate challengers are running neck-and-neck with increasingly unpopular Republican incumbents Thom Tillis in North Carolina, Cory Gardner in Colorado, Joni Ernst in Iowa, and Martha McSally in Arizona. Winning races like these will be essential if Democratic presidential contenders hope to deliver on any of their lofty campaign pledges.

A figure like $47 million could have been game-changing when spread across tight races—especially when Democrats have the rare opportunity to flip the Senate and break a decade of Republican obstruction. But instead of strengthening the party as a whole, Steyer chose to spend that money on—himself.

Without the privilege of his boundless wealth, most voters wouldn’t even know Steyer’s name. His campaign exists not because of any popular call for his candidacy or particular policy expertise, but because Steyer has pockets deep enough to thrust his face in front of every single Democratic voter with a television, radio, computer or mailbox.

That isn’t an exaggeration. Fully 67 percent of all spending on television ads across the entire Democratic primary has come from Steyer’s bank account. When flooding the zone with money is your only strategy, every problem starts to look like a money problem. Maybe that’s why Steyer’s campaign thinks democracy is for sale.

Just last week, Steyer’s Iowa operation faced a scandal when state director Pat Murphy resigned after offering elected officials cash in exchange for endorsing Steyer. The perception of attempted quid pro quo arrangements by the Democratic race’s largest self-funder should leave a bad taste in the mouth of any voter who looks at Donald Trump’s current impeachment woes with disappointment and disgust.

Clearly, DNC debate requirements must be strengthened. In the future, the DNC should consider not only the raw number of donors a candidate must generate—currently 165,000—but also the proportion of campaign funds coming from grassroots donors compared to the total raised. In Steyer’s case, despite raising nearly $50 million, only 4 percent came from actual voters.

More worrisome is the message Steyer’s campaign sends to other deep-pocketed, misguided billionaires looking for a new hobby. Former New York City Mayor and current multibillionaire Michael Bloomberg recently floated his own entry into the Democratic primary.

If Bloomberg runs, he plans to implement an even bolder version of the Steyer Strategy. The Associated Press reports Bloomberg will pass on early primary states like Iowa and New Hampshire in order to deploy his immense $52 billion fortune in a slew of pricey Super Tuesday media markets. By purchasing a larger voice than any other presidential contender, Bloomberg hopes to shock-and-awe Democratic voters into supporting his platform of—well, it’s not really clear, actually.

When campaign treasuries are independently generated, they cease to be reflective of a candidate’s actual popularity. In his decision to skip early states in favor of spending his way to prominence on Super Tuesday, Bloomberg is choosing his own voters.

Steyer and Bloomberg put the arrogance of plutocratic wealth on full display. Where traditional candidates are dependent on voters who contribute the money that becomes campaign advertising, both Steyer and Bloomberg are beholden to only one donor: themselves. In a nation where money has been declared equal to speech, the candidates who can funnel the most cash to themselves will inherently be more visible – and in the case of Democratic debate rules, just popular enough.

It is perverse that the Democratic Party, an organization so vocally in favor of regulating the sprawling power of plutocrats, has left itself open to such crude manipulation of our nomination process. It is on the party to make necessary changes that prevent this kind of blatant gaming of the system going forward.