Royalist is The Daily Beast’s newsletter for all things royal and Royal Family. Subscribe here to get it in your inbox every Sunday.

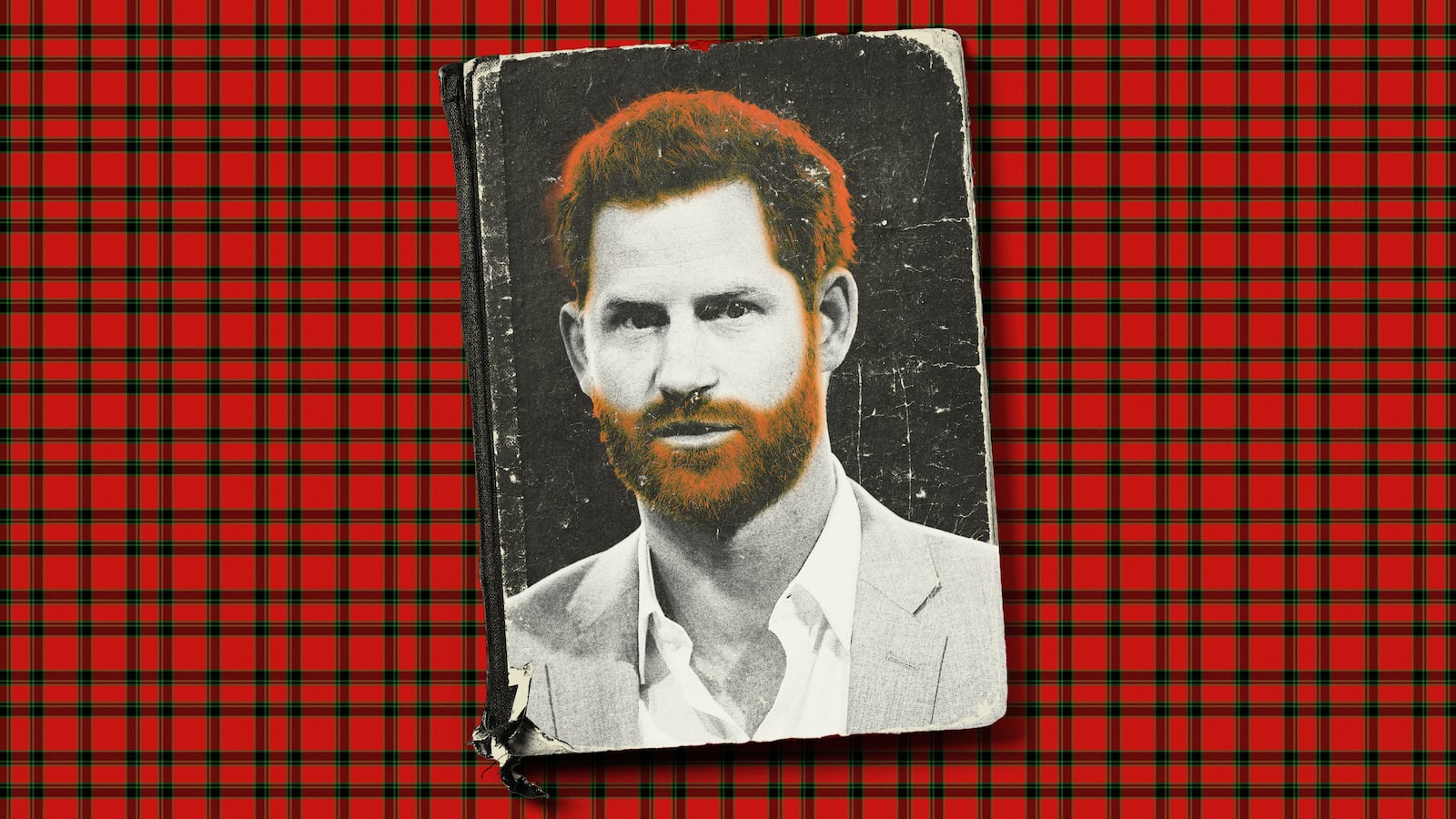

J.R. Moehringer is a ghost in more ways than one: as the Pulitzer-winning writer of Prince Harry’s ominously cathartic memoir, and as a name that may well come to haunt the Windsors in the same way that Harry’s mother, Princess Diana, always does.

The prospect of a royal story, particularly one as potentially incendiary as Harry’s, being subjected to the techniques of literary journalism, building tension through novelistic pacing and voicing emotions normally absent from straight reporting, is raising red flags among some royal historians.

Robert Lacey, himself a distinguished royal biographer, told me, “The power of Harry’s book will lie in the emotional experience—but not as lived through his eyes. It will derive its impact through the applied eye of Moehringer. When Harry talks about the “genetic pain and suffering that gets passed on” he sounds to me more like Moehringer than Windsor.”

Moehringer won his Pulitzer for Crossing Over, a tour-de-force of literary journalism published in the Los Angeles Times Magazine in 2000. He tells the story of Mary Lee, a woman living in Gee’s Bend, Alabama, a Black community geographically isolated from white communities by a bend in a river. The story pivots on the impending arrival of a new ferry that will end that isolation. Moehringer channels the dark history of Gee’s Bend through the voice of Mary Lee, creating a powerful montage of hope and tragedy that has the pacing of a documentary film.

This is a far higher level of writing craft than is usually called upon to produce a ghosted celebrity autobiography. That was already clear when Moehringer ghosted Andre Agassi’s autobiography, Open, a searing account of a life spent inside the talent grooming machine of professional tennis, published in 2009, in which, once more, he found a narrative voice that seemed authentic and deeply personal.

Lacey linked the influence of Moehringer with that of Meghan: “…two tough Americans imprinting their own radical thought patterns onto a malleable young Brit who uses their words to fight his family battles.”

But I don’t agree. First of all, the diminishment of Harry’s agency, a frequent British trope tied to the idea “she made him do it.” And then, the idea of a ghost writer using his subject as a ventriloquist for his own views isn’t borne out by Moehringer’s track record. He wouldn’t need to take his own axe to the Windsors, even if so inclined, which is unlikely, because Harry’s disaffections are already well aired. What is more, the impact of this book will be formidable because Moehringer’s craft will lift it above the ghost’s usual device of giving a celebrity a fluency that they don’t have, while avoiding any real substance.

Harry has every right to tell his story, and to have it told well. Far better that he is the clear unadulterated source rather than behave as he and Meghan did with Finding Freedom, the version of their lives written by Omid Scobie and Carolyn Durand, where they denied helping the authors in any way only to have to retract when, in a court case, their press secretary confessed that they had passed on their own “briefing points” and been given the opportunity to check facts.

As a reporter, Moehringer will have seen that the most under-reported part of Harry’s life is his military service in Afghanistan, the experience that immersed him in the brutal realities of the killing fields and left him with a place in the army brotherhood that no other royal has ever earned. (Andrew, in contrast, who loves to wear medals, was disowned by the military after his Epstein entanglement.)

Lacey agreed that Afghanistan would be an important part of the book, but added, “It is worth emphasizing that he was only allowed to see active service, unlike William, because his life was judged expendable. This did not worry him at the time, but is exactly the sort of factor that Meghan will have played on for her own reasons.”

That stuff would not, however, be what would be damaging to the Windsors. They will worry more about the earlier emotional journey through Harry’s memories of Diana and his father’s maladroit attempts at parenting after her death, when the paramour Camilla moves in and becomes the Duchess of Cornwall, as well as delving into how that same experience was handled by his brother.

This is the kind of personal revelation that has always been anathema to the family. It was Diana’s openness about her inner life that they hated, as they have always hated any narrative that describes their lives in any terms other than the authorized fairy tale.

“Utterly oyster”

The first person to discover this was Marion Crawford, nanny to the young Princess Elizabeth and her sister Margaret. Known as “Crawfie” in the household of King George VI, she was so trusted that she was regarded as almost a member of the family, having been with them throughout the Second World War.

After Crawford retired in 1948, she collaborated with a writer for Ladies Home Journal on a memoir. The current queen’s mother, Queen Elizabeth, was tipped off and wrote to Crawford: “I do feel, most definitely, that you should not write and sign articles about the children, as people in positions of confidence with us must be utterly oyster…you must resist the allure of American money…”

Princesses Elizabeth (second left) and Margaret are accompanied by Lady Helen Graham (left) and governess Marion Kirk Crawford (right) as they arrive for their first ride on a London Underground tube train at St James’s Park, London, May 15, 1939.

Central Press/Hulton Archive/GettyCrawford defied that warning and the serialized articles and subsequent book, The Little Princesses, were blockbusters. In fact, the former nanny had revealed nothing sensational—it was an anodyne and adoring account but, nonetheless, the family never spoke to her again. The point was not that this decent, humanizing portrait ought to have been seen by the Windsors as a public relations coup, not a hanging offense, but that they had a deep-rooted aversion to any glimpse of their lives that they could not control themselves. “Utterly oyster” was a mafia-level oath of allegiance and silence.

At around the same time that American money was luring Crawford, it was also being offered to a member of the royal family who was beyond any appeal to keep his mouth shut, the Duke of Windsor, the one-year monarch Edward VIII. Since his abdication in 1936 the Duke had been in exile, spending much of his time in America, where Henry Luce, czar of the Time Life empire, commissioned a series of ghosted autobiographical articles that eventually led to a book, A King’s Story, a shamelessly self-serving account of his life up to 1936.

The Palace was outraged. Tommy Lascelles, George VI’s most powerful courtier, who had served the young Duke as an assistant private secretary and loathed him, admitted in a note to the king that nothing could be done to stop the book: “I am sorry to say that long experience has convinced me that he has no such feelings when the interests of the Monarchy or Royal Family conflict with what he imagines to be the interests of himself and the Duchess.”

When the book came out in 1951, the New York Times reviewer pretty much nailed it in one sentence as “a character study of a well-meaning, undistinguished individual, destined from birth to a life of monumental artificiality.” Nonetheless it was a best seller and was a mother lode for the Duke, a lavish spender and frequent mendicant, earning him nearly ten million pounds in today’s money.

Once more, the distress of the Windsors was not about the content. If anything, the book confirmed their view of the Duke as pitiful narcissist. It was about the defiant decision to publish, without giving the Palace any chance of intervening.

In fact, Lascelles was used to being obeyed as the family’s censor of anything written about them. At the same time as the Duke’s book was being ghosted, a new biography of his mother, George V’s widow, Queen Mary, by James Pope-Hennessy, was vetted by Lascelles, who reported: “Is there anything in the book that could offend or distress, The Queen herself, or any member of her family?—Answer, No, nothing. It is throughout written in perfect taste—the book of a gentleman, rare in these days.”

That last clause suggests that Lascelles already sensed that the upper-class Edwardian code of conduct he grew up with, invested in the definition of quiet agreements between clubbable “gentlemen,” was slipping away.

But now, a lifetime later, the spirit of Lascelles seems astonishingly to be still alive in the way that Harry’s book is being viewed within the family. For the queen, Lascelles remains very much a fondly remembered tutor and guardian, not an irrelevant anachronism. She would surely wish that the old code held good - the ramparts of her own privacy are as unviolated as they were in the 1950s.

However, it has to be said that the queen was herself guilty of applying a double standard in the way that offenders were treated by the family. As usual, it was the servant class that got stiffed. Crawford bought a house near Aberdeen that was on the route taken by the royals bound for their summer retreat at Balmoral.

Each year she watched as they passed, but they never stopped, while the Duke of Windsor, once the Hitler-schmoozing pariah, was allowed back for a late life reconciliation and a place next to his wife in the royal burial ground—near Frogmore House, Windsor, briefly the home of Harry and Meghan.

Lord Palumbo greets Princess Diana, wearing a short black cocktail dress designed by Christina Stambolian, as she attends a gala at the Serpentine Gallery in Hyde Park on June 29, 1994, in London.

Tim Graham Photo Library via GettyThere were no more serious alarms about royal biographies until 1992, when the queen reached her fortieth year on the throne. For ten years, Princess Diana had lived through the steady disintegration of the classic fairy tale marriage she had signed up for. Then along came Andrew Morton, who had developed the killer instincts of tabloid journalism at Rupert Murdoch’s News of the World, but he found himself with a story far bigger than could be told in the tabloid demotic.

His book, Diana: Her True Story, lived up to its title. It recounted in detail the vitriolic battle of attrition between Diana and Charles, and was so raw that it blew up every convention of what was permissible in a royal biography. To make the experience worse for the Windsors, the book was serialized over two weekends in Murdoch’s flagship paper, the Sunday Times.

After Diana’s death, Morton revealed what had long been suspected, that Diana had collaborated with him, shaping what became a very public bias against Charles and Camilla and clearly setting out her own sense of victimhood.

In an extensive interview, Morton told my colleague Tom Sykes what he thinks about the BBC’s recent decision to deep six the interview with Diana they broadcast three years after his book was published—which was, as he said, mostly a televised version of his book.

Prince William was instrumental in burying the interview, on the basis that the BBC reporter, Martin Bashir, used unscrupulous methods to obtain it, which is true. Nonetheless, as Morton points out, that does not invalidate anything Diana said: “This is an important, historic interview that should be part of the public record. No accurate history or documentary of Diana can be made without referencing that interview.”

Whether he realizes it or not, William has fallen into line with the regime established by Lascelles. For several generations, the Windsors have hijacked large chunks of British history and purged them of anything they think might embarrass them. The most serious offenders, to them, remain members of the family who break the sacred pledge of the royal omerta.

It took Harry and Meghan a while to figure out how to wrest control of their own messaging from this system. Their first attempt was spelled out in the short-lived but consequential website they launched in 2019, Sussex Royal (which broke the record for pulling in a million followers, set by Instagram, by achieving that number in less than six hours).

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle arrive to attend the annual Commonwealth Day Service at Westminster Abbey on March 9, 2020, in London.

Dan Kitwood/GettyThe website set out the rules for how they would collaborate with reporters. They were, they said, prepared to “engage with grassroots media organizations and young, up-and-coming journalists; invite specialist media to give greater access to their cause-driven activities; provide access to credible media outlets focused on objective reporting.”

In other words, they were trying to establish an alternative journalism on their own terms. This was not surprising, given the hostility shown to them by much of the British media, but it revealed an almost touchingly Panglossian belief that better angels would appear. How would this work? Where were the “young, up-and-coming journalists” ready to oblige?

They didn’t have to worry about that, once they chose to make a runner from their royal duties in 2020. They were soon headed to a far more sympathetic audience, America—and Oprah.

And now, it seems, in Moehringer, Harry has found his ideal amanuensis, a writer who can set a new bar for the literary quality of a royal memoir. How far will that elevate the threat to the Windsors?

Robert Lacey told me, “I’m sure that while the book does present the Windsors with what might be described as a threatening moment, there have been many such ‘threats’ before. Love or loathe the monarchy, the negative books and articles and all the many truths they have told so powerfully have presented no meaningful threat to the existence or continuation of the monarchy. If anything, they have only served to confirm its permanence in the anthropology of British culture.”

In other words, this one will run and run—but so, as sheer entertainment, if nothing else, will the Windsors.