Come 2016, I probably won’t #StandwithRand.

Much as I might admire some of the “libertarian-ish” stances taken by Rand Paul, the filibustering junior U.S. senator from Kentucky and early favorite for the 2016 GOP presidential nomination, my left-leaning heart will probably belong to someone else in the next general election. There are too many issues on which his viewpoint and mine diverge.

However, as a physician, there is one area in which I have significant sympathy for one of Sen. Paul’s controversial positions: specialty board certification.

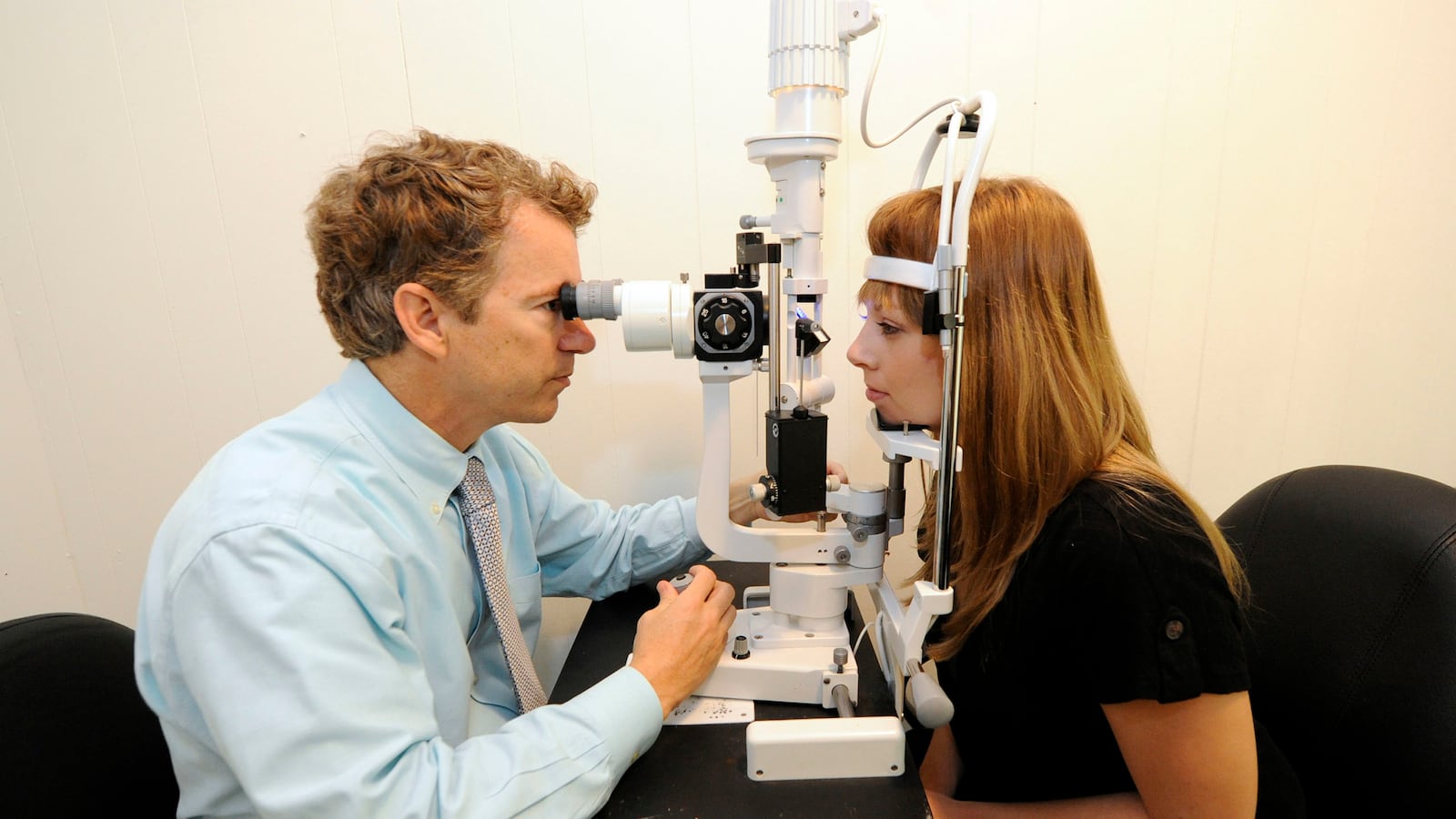

Like his father Ron, Sen. Paul is a doctor—the older Paul is an OB/GYN, the younger an ophthalmologist. Back in the 1990s, he ran afoul of the American Board of Ophthalmology (ABO), the certifying organization for his specialty. As reported in The Washington Post, Paul objected to a rule change by the board that exempted ophthalmologists who had been certified before 1992 from having to recertify every 10 years. Having been certified after that date, he found the rule change unfair. In protest, he founded the now-defunct National Ophthalmology Board, and continued to describe himself as “board-certified” with its imprimatur.

Unlike a medical license, which each state requires in order to practice medicine, I don’t need board certification to take care of patients. My certification is from the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP), which like the ABO is part of the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS). I can open a practice and prescribe medications whether or not I have it. But I can’t call myself a “board-certified” pediatrician without it. These days getting a job as a doctor, regardless of specialty, is essentially impossible without board certification, and neither of the hospitals where I have admitting privileges would appoint me to their active staff if I didn’t have it.

Sen. Paul’s beef with the ABO is one of his more libertarian stances. Milton Friedman, perhaps the most prominent libertarian intellectual of the past century, objected even to medical licensure as an undue burden on the free market. While I disagree with Friedman and consider licensure an important measure to protect the public from incompetent physicians, many of his criticisms seem to fit the ABMS.

A system to ensure that providers have a baseline competency in the areas where they choose to practice makes sense to me. When I was initially certified by the ABP, the requirements were essentially limited to having completed a pediatrics residency and passing a very challenging exam. Unlike Sen. Paul, I don’t even object to retaking the exam every 10 years, and I just did so last year. But recently the obligations have gotten significantly more tedious and burdensome.

Under a new system called Maintenance of Certification, all member boards require diplomates to do some kind of ongoing “practice performance assessment.” The specifics vary from board to board. In the case of the ABP, we are required to do Quality Improvement (QI) projects, which (PDF) look roughly similar to what all the other boards require. This may seem like a good idea in theory, but in practice they amount to glorified extra-credit projects and pointless busywork.

There are already numerous burdens placed on physicians to keep practicing their profession. I am required by both the licensing board in my state, and the medical staff offices of the hospitals where I am on staff, to get a certain number of hours of continuing medical education (CME) every couple of years. CME credit is the coin of the realm for medical conferences, and there’s little point in attending one if it doesn’t count toward the required tally. I’m not allowed to just sit around and let my knowledge base calcify.

Furthermore, insurance companies have begun looking at quality measures as a way of determining how much they will compensate doctors for the services they provide. Outcomes like reducing the number of times patients go to the emergency department for care or how well their asthma is managed are starting to factor into how much physicians are paid.

But that’s not enough for the ABMS. A not-for-profit organization accountable only to itself, it can set and change its standards at will. As diplomates have little choice but to comply, all of us now have to incorporate these little QI projects into our copious spare time. Attempts by The Daily Beast to contact the ABMS for comment by phone and email were unsuccessful.

As Dr. Jennifer Hester, a St. Louis internist, told The Daily Beast, “I do not think the new MOC requirements truly reflect my competence as an internist. I'm not 100 percent sure what the American Board of Internal Medicine [another member board of ABMS] hopes to accomplish with its new MOC requirements, but the consensus [among my colleagues] seems to be that this new program is meant to fill a budgetary gap.”

All of this is supposedly for the public’s benefit. As quoted by the Post in its coverage of Sen. Paul’s board certification controversy, Beth Ann Comber of the ABO said, “Board certification, and especially MOC participation, by an ABMS-recognized board helps patients make more informed choices regarding their medical care.” This is, of course, laughable. It defies credulity to posit that any given patient is even remotely aware that MOC exists or what it means, much less that any significant number are checking up on it.

Later in the same article, Comber said, “Certification is voluntary, so physicians who make the choice to participate in continuous learning and quality improvement activities are doing so out of a personal commitment to high standards for their patients and their practice.” Certification is voluntary only insofar as work as a physician is voluntary. My personal standards are indeed quite high, but that has nothing to do with my enrollment in the MOC process. I have no real choice in the matter, regardless of what the ABO or ABP or ABMS say.

If all of this seems complicated and difficult to follow, as a physician trying to keep up it most certainly is. While I truly love being a pediatrician and caring for my patients, more and more doctors are finding the practice of medicine an unforgiving and wearying profession that no longer seems worth it.

As Dr. Hester puts it, “The new MOC process comes at an especially hard time for all of us. It seems to add insult to injury in this profession that once seemed noble, and now just seems like a whirlpool from which none can escape.”

I lack the wherewithal to start my own competing certifying board, to say nothing of the chutzpah. But whatever my other qualms with Rand Paul’s political agenda, I cannot fault him for trying to find a way around the ABMS’s cartel. I suspect I am not alone among physicians along the political spectrum who otherwise have little common ground with him. If I were a single-issue voter, he’d have mine in 2016.